Waldorf Graduates Pursue Meaningful Careers

Will My Child Succeed After Waldorf High School? The Research Says Yes

Choosing a high school is a critical decision, and parents often wonder: Will this education prepare my child for college, career, and life?

For families considering Waldorf high schools, this question is especially relevant. With experiential learning, seminar-style discussions, and an interdisciplinary curriculum, can Waldorf truly equip students for fields like medicine, law, technology, and business?

Decades of research say yes.

Waldorf Graduates Excel in Higher Education and Careers

A 60-year study (Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II, Mitchell & Gerwin, 2007) found that:

- 94% of Waldorf graduates attend college.

- 42% major in science-related fields—more than double the national average.

- Many earn advanced degrees in medicine, law, engineering, business, and the arts.

- Alumni thrive in fields ranging from finance and research to entrepreneurship and sustainability.

Waldorf Alumni Spotlight: Science in Action

After earning a degree in Earth Systems Engineering from the University of Michigan, Gavin Chensue ('06) joined the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps, leading critical climate studies worldwide.

"Steiner education gave me a taste of everything. When I needed direction in college, I remembered how much I loved studying weather and geology—and that led me to where I am today." - Gavin Chensue (RSSAA '06), Research Engineer at SRI International, Former NOAA Corps Officer

His story highlights how Waldorf graduates succeed in STEM, combining curiosity and real-world problem-solving to make a global impact.

Read the full studies:

- Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/research

- Into the World Study: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/graduate-outcomes

What Makes a Waldorf Education So Effective?

Contrary to the belief that test-driven education leads to success, research shows that employers and universities highly value graduates who:

✔ Think critically and independently

✔ Communicate clearly and persuasively

✔ Collaborate effectively

✔ Solve complex problems

✔ Adapt to a changing world

These are precisely the skills Waldorf high schools cultivate.

1. Depth Over Memorization: Lifelong Knowledge Retention

Rather than rote memorization, Waldorf fosters deep understanding:

- History is explored through primary sources and narratives.

- Science emphasizes hands-on experiments and independent research.

- Mathematics focuses on real-world application.

- Literature and philosophy encourage analytical discussions.

One employer noted:

“Waldorf students don’t just look for the right answer—they explore the why and how behind complex issues.”

2. Seminar-Style Learning Develops Exceptional Communicators

Waldorf emphasizes oral presentations, debates, and collaborative discussions, preparing graduates for leadership roles in law, finance, business, and medicine.

Dr. Ilan Safit, co-author of *Into the World*, states:

“We consistently hear that Waldorf graduates excel at teamwork and leadership. Their ability to articulate complex ideas is a major asset.”

A study from Da Vinci Waldorf School found that Waldorf students select careers based on values and passion rather than prestige or income.

Final Thoughts: The Research Speaks for Itself

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Read more on Waldorf Graduates

Selecting a High School

Selecting a High School

Advice from Veteran Waldorf Educators

Choosing the right high school can feel like one of the most significant decisions a family will make in their child’s educational journey.

To bring clarity to this decision, we turned to two of our most experienced educators at the Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor: Margot Amrine, a longtime Waldorf teacher with over four decades of experience, and Dr. Siân Owen-Cruise, our former School Administrator, who has guided countless families through the high school selection process.

Today’s parents listen to and respect their children’s perspectives more than ever before- a positive shift in family dynamics. But as Margot reminds us, that doesn’t mean parents should surrender their leadership on big decisions.

“In our family we said that Waldorf Education for 9th and 10th grade was essential. At 11th grade, a different kind of maturity sets in; if our children had made compelling reasons to leave then, we would have considered. We never had these discussions!”

Dr. Owen-Cruise expands on this, acknowledging that social pressures play an outside role in an 8th Grader's thinking:

“It's natural for teenagers to focus on their peers and social dynamics when thinking about high school. As parents, we listen, we understand, and we take their feelings seriously- but ultimately, we need to lead this decision with wisdom and foresight.”

Dr. Owen-Cruise often frames the conversation with the rising student in the following way:

“Your parents will choose where you receive your high school education, with your input. YOU will choose where you go to college, with our parental input.”

Many families who have walked this path find that their children- whether they started in Waldorf Education or joined from another school-ultimately express gratitude that their parents guided this decision with their long-term development in mind.

Here are some other helpful tips and information when thinking about our own High School:

Waldorf Graduates Pursue Meaningful Careers

“Will My Child Succeed After Waldorf High School? The Research Says Yes” - Blog Article

Parents often ask: Does a Waldorf education prepare students for college, careers, and beyond? The answer is a resounding yes. Studies show that Waldorf graduates not only attend college at high rates but also excel in fields like science, medicine, law, and technology. Employers and universities consistently praise their ability to think critically, communicate effectively, and adapt to a changing world. Want to know why? This article dives into the research and real-world successes of our alumni.

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

"The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens" - Blog Article

In an age where screens dominate every aspect of life, imagine a school where students engage in real conversations, dive into hands-on projects, and focus fully in class—without the pull of notifications. Our phone-free policy isn’t just a rule; it’s a game-changer. See how it shapes our students’ social and academic lives!

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

Imagine a typical school day where students, between classes and during breaks, are glued to their smartphones—scrolling through social media, playing games, or texting. Conversations are sparse, eye contact is minimal, and the vibrant energy of youthful interaction seems subdued. Now, contrast this with a school environment where smartphones are set aside: students engage in lively face-to-face discussions, participate in spontaneous games, and immerse themselves fully in classroom activities without the constant pull of notifications. This is the reality we’ve cultivated at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, embracing a phone-free policy that fosters genuine connections and holistic development.

The Deeper Engagement of Phone-Free Education

At our school, we’ve observed that removing smartphones from the school day does more than just eliminate distractions—it rekindles a deeper, more meaningful engagement among students. Freed from screens, students rediscover the joy of direct communication, collaborative problem-solving, and hands-on learning. This environment aligns seamlessly with the principles of Waldorf education, emphasizing experiential learning and nurturing the whole child.

We Are Phone-Free, Not Tech-Free

While our school maintains a phone-free environment during school hours, we are not devoid of technology. In fact, our curriculum incorporates technology in age-appropriate ways to ensure students are prepared for the digital world:

• Middle School: Students are introduced to computers and the internet in an intentional way that supports learning. Additionally, our middle school robotics club fosters interest in technology and engineering through hands-on projects. https://www.steinerschool.org/programs/extracurricular-activities.cfm

• High School: Our state-of-the-art computer lab facilitates courses in coding, digital literacy, and other computer science subjects. We also have an active high school robotics club where students collaborate on competitive projects that develop real-world problem-solving skills. https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-education.cfm

Many of our graduates go on to thrive in technology fields, excelling in computer science, engineering, and data analysis. Research shows that Waldorf graduates develop strong interdisciplinary thinking skills that prepare them for success in fields that require both creativity and technical expertise.

Leading the Way in Ann Arbor

Our commitment to a phone-free school day positions us as pioneers in the Ann Arbor educational community. While some other local schools have implemented partial restrictions, our comprehensive approach ensures that students remain unplugged throughout the day—including breaks and transitions between classes.

Several Ann Arbor schools are recognizing the value of limiting phone use:

• Forsythe Middle School and Tappan Middle School both require students to keep phones in lockers during school hours. https://forsythe.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy, https://tappan.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy

• Huron High School has introduced classroom phone storage policies in its Mathematics and English departments to help students stay focused. https://thehuronemery.com/9731/news/cell-phone-use-teacher-led-procedures-to-enrich-student-experience/

The Transformative Power of Disconnecting

The shift to a phone-free environment has yielded profound benefits:

• Enhanced Academic Focus: Without the allure of smartphones, students engage more deeply in lessons, leading to improved comprehension and retention.

• Strengthened Social Bonds: Face-to-face interactions during breaks and collaborative projects foster authentic relationships and empathy among students.

• Improved Mental Well-being: Reducing screen time has been linked to decreased anxiety and stress, allowing students to be more present and mindful.

Embracing a Connected Future Without Phones

As more schools recognize the value of limiting smartphone use, it’s evident that this movement is not about restricting technology but about reclaiming the essence of human connection and focused learning. By leading the way in this initiative, Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor not only adheres to the foundational principles of Waldorf education but also prepares students for careers in STEM, the arts, and beyond.

We invite families seeking a nurturing, distraction-free educational environment to join us in this journey, where students can truly engage with the world around them and develop into well-rounded individuals.

Explore the experiences of other schools with phone-free policies:

• “New data reveals shocking trend since school mobile phone ban”

- “The big smartphone school experiment”

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/inside-schools-ban-smartphones-6knb8qtfc

- “Cell phones hinder classroom learning. Texas should tell school districts to lock them up”

- "Waldorf Schools are Media Literacy Role Models"

https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-schools-are-media-literacy-role-models/

A Thoughtful Approach to Homework

Too often, homework can be meaningless busywork that stresses and overwhelms students and their families, crushes creativity, and has little impact on children's future success. In Waldorf education, we take a thoughtful, age-appropriate and balanced approach, where homework is introduced later, and is focused on meaningful assignments that foster creativity and further their understanding. Assignments will often include an artistic or project-based component as well. Our approach to homework is rooted in sparking students’ imagination and creativity, helping them to learn to articulate their understanding and viewpoint, and cultivating a strong love of learning. The aim is to ensure that students are leading healthy balanced lives that include time for rest, recreation, free play and family time.

Originally published in The Atlantic by Joe Pinsker

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed, which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s. Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study, for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s. Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study, for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s, and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing, considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork, while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”

“Exploratory” is one word Mike Simpson used when describing the types of homework he’d like his students to undertake. Simpson is the head of the Stone Independent School, a tiny private high school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that opened in 2017. “We were lucky to start a school a year and a half ago,” Simpson says, “so it’s been easy to say we aren’t going to assign worksheets, we aren’t going assign regurgitative problem sets.” For instance, a half-dozen students recently built a 25-foot trebuchet on campus.

Simpson says he thinks it’s a shame that the things students have to do at home are often the least fulfilling parts of schooling: “When our students can’t make the connection between the work they’re doing at 11 o’clock at night on a Tuesday to the way they want their lives to be, I think we begin to lose the plot.”

When I talked with other teachers who did homework makeovers in their classrooms, I heard few regrets. Brandy Young, a second-grade teacher in Joshua, Texas, stopped assigning take-home packets of worksheets three years ago, and instead started asking her students to do 20 minutes of pleasure reading a night. She says she’s pleased with the results, but she’s noticed something funny. “Some kids,” she says, “really do like homework.” She’s started putting out a bucket of it for students to draw from voluntarily—whether because they want an additional challenge or something to pass the time at home.

Chris Bronke, a high-school English teacher in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove, told me something similar. This school year, he eliminated homework for his class of freshmen, and now mostly lets students study on their own or in small groups during class time. It’s usually up to them what they work on each day, and Bronke has been impressed by how they’ve managed their time.

In fact, some of them willingly spend time on assignments at home, whether because they’re particularly engaged, because they prefer to do some deeper thinking outside school, or because they needed to spend time in class that day preparing for, say, a biology test the following period. “They’re making meaningful decisions about their time that I don’t think education really ever gives students the experience, nor the practice, of doing,” Bronke said.

The typical prescription offered by those overwhelmed with homework is to assign less of it—to subtract. But perhaps a more useful approach, for many classrooms, would be to create homework only when teachers and students believe it’s actually needed to further the learning that takes place in class—to start with nothing, and add as necessary.

Integrating Science and Art with a Sense of Place: The Waldorf Senior Zoology Trip

Originally published in the Spring 2023 Renewal Magazine

The sun has set, and the sound of the surf is heard just outside this empty wooden building. One hundred Waldorf seniors on this year's trip are out at the ocean's edge on the star-lit beach making ablution. They cleanse their hands, feet, and face in the cold ocean water, purify and calm their minds and then quietly open their senses to the nature of this island they will inhabit this week.

The sun has set, and the sound of the surf is heard just outside this empty wooden building. One hundred Waldorf seniors on this year's trip are out at the ocean's edge on the star-lit beach making ablution. They cleanse their hands, feet, and face in the cold ocean water, purify and calm their minds and then quietly open their senses to the nature of this island they will inhabit this week.

Slowly they re-enter the Kelp Shed, most holding the silence they were asked to keep. The room is dark, but a fire crackles loudly in the stone fireplace of this rustic, homey shed that serves as lodge for the summer campground. The rhythmical strumming of a guitar begins as the teachers sing a chant that has started each of these trips. "The earth ... the air. .. the water. .. the fire. .. return, return, return, return." As the music makes space, students join along singing, tentatively at first, but with growing confidence. Then silence. One teacher asks the group to imagine a picture of the quality of earth, and how it shapes this place and our lives. The rhythm of chant, silence, and picturing continues weaving through all four elements. Then silence. As the evening ends, the students and teachers file out to walk back to their campsites together. Another year of the senior zoology trip has begun.

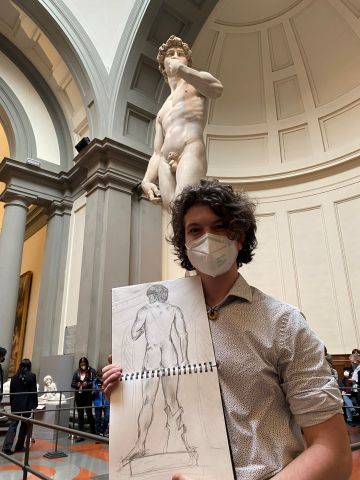

Waldorf science education is rooted in a phenomenological approach. This means that observing phenomena is the key first step. Equally important is the reflective aspect of lessons where teacher and students grapple with previously made observations to come to meaningful relationships. We strive not just to fill the students with facts, but to awaken their capacities for observation, thinking, and artistic expression. Through engaged thinking, students are in the true process of "doing science," not just learning what other people have discovered. When taught well, science lessons awaken an interest in the world and in thinking more deeply about it. Doing this in the novel environment offered at Hermit Island on the Maine coast provides a capstone experience in the natural sciences. The artistic workshops connect the artistic realm to the scientific experience. Paintings, poetry, and observational drawings of marine invertebrates created by students in their field notebooks provide a true integration of art and science.

Student response to the trip has been enthusiastic. An international student from Ann Arbor told me. "I've seen all of the marine animals on TV. I felt like I knew everything about them. But when I interacted with them in the tide pools and observed the live animals under the microscope, I realized that I didn't really know anything. Now, I actually know them." Another student wrote a typical reflection about the week "I am tremendously grateful for this past week's endless opportunities. growth experiences, and lessons." Over the years, many have identified this as being a favorite experience of senior year.

Recently, I had a conversation with Edward Edelstein, trip founder. His love for marine biology began while tide pooling and snorkeling for abalone on the coast of California as a high school student. As a biology teacher at Ontario's Toronto Waldorf School in 1993, Edelstein wrote a letter to all Waldorf High School biology teachers east of the Rocky Mountains proposing a senior trip to study marine zoology at Hermit Island, where he had vacationed with his family. He got only one positive response. Andy Dill from the Kimberton Waldorf School said he would give it a try and the first Hermit Island trip was launched with two schools in the fall of 1994.

Recently, I had a conversation with Edward Edelstein, trip founder. His love for marine biology began while tide pooling and snorkeling for abalone on the coast of California as a high school student. As a biology teacher at Ontario's Toronto Waldorf School in 1993, Edelstein wrote a letter to all Waldorf High School biology teachers east of the Rocky Mountains proposing a senior trip to study marine zoology at Hermit Island, where he had vacationed with his family. He got only one positive response. Andy Dill from the Kimberton Waldorf School said he would give it a try and the first Hermit Island trip was launched with two schools in the fall of 1994.

Year by year, attendance grew. At its pre-COVID peak there were 17 schools and over 240 students attending over two weeks. Over the past quarter century, several thousand Waldorf seniors have participated in this unique experience.

Zoology has always been at the heart of the trip, not just in the scientific work, but also in such details as the subjects of artistic projects, names of lab groups, and orchestration of evening campfires. Each day, one of the key invertebrate animal phyla (mollusks, annelids, arthropods, and echinoderms) forms the topic for the main lesson presented by collaborating teachers from each school.

Our study is deepened during the daily tide pool, microscope, and ecology labs, which are balanced by artistic workshops. Tidal rhythms sometimes require pre-dawn marches to the rocky shore so the students can experience the tide pools at a 6:00 a.m. low tide. These activities encourage students to enter genuinely into the context in which the marine invertebrates thrive. Experiencing them in their environment is key to understanding these animals. Hermit Island, with its unusual diversity of habitats, allows us to experience not only the animals in the context of their homes, but the amazing beauty of nature on this Maine coast.

An alumna of the class of 2013 recently shared the following reflections from her trip 10 years ago. "Hermit Island was a huge trip for me. I had never seen an ocean until we pulled up to Hermit Island. That alone was life changing. I had always wanted to experience being by an ocean so close to that expanse of water that is wild and calming and vast. [The trip] opened the senior year in such a unique way. It set that school year apart, making it special from the beginning. It allowed us to connect with people from other Waldorf schools. It allowed us to really bond as a group, away from the rest of the school. I don't have a single bad memory from that trip. I remember it in music, in the book whose author came to speak that I immediately bought at home, in sunshine, mud, pine trees, porcupines fighting in the trees, feeling free. I remember sitting alone on a cliff on our reflection morning and feeling so happy in that place.”

The opening evening ablution and elements circle sets the tone for the week. Sitting at the computer reflecting on the trip, the simple chant echoes on in me. "The earth, the air, the water, the fire, return, return, return, return.” These four elemental qualities contain deep wisdom. When I think of Hermit Island, the pictures of those qualities arise in me: sand, rock, and mud beneath our feet as we explore the different ecosystems; wind raising the surf and bringing the freshness of the ocean's salty water; cold tide pools, home to periwinkles, sea urchins, tunicates, crabs, and sea stars; the fiery sun warming us in the early morning's chill; the crackle of the evening's campfire, calling us to share and listen.

If you ask one of the students who attended the trip, “What happened in Maine?” you may get many answers, but key among the themes I have found are transformation, connection, joy, and amazement. We will continue sharing this experience with other Waldorf students and teachers as we return for another trip in September 2023.

.jpg/PXL_20210913_144803431(1)__427x320.jpg)

Steiner School Waboba Experiment

Originally Published in the Waboba Journal

Earlier this year, Noelle Frerichs, a physics teacher at Rudolf Steiner High School in Ann Arbor, Michigan, reached out to us about wanting to get her hands on Waboba Pro Balls for an upcoming classroom experiment she was doing. The experiment would involve throwing balls up in the air to calculate the height of each throw using knowledge of the speed of free fall. At first we offered to send Moon Balls since they bounce super high, but Noelle advised it was best to stick with the Waboba Pro balls to get the desired results. (Moon Balls would hit the ceiling in the gym, which would make it problematic for the calculation. Naturally.)

You see, Noelle was planning a series of labs for her 10th grade physics (mechanics) class, where the students discover the acceleration of objects in free fall and learn to calculate the speed and height of a projectile. She thought of the gel Waboba balls because her dog has the pet version - the Waboba Fetch (she has 4, a true furbobian). Noelle knew her students would feel safer trying to catch soft Waboba balls over a hard softball, and others would feel safe with balls flying over their heads too. Plus, they could do the experiment in the gym if needed, and the Pro balls would be heavy enough to get good height, minimizing the effect of air resistance, which would skew their results.

You see, Noelle was planning a series of labs for her 10th grade physics (mechanics) class, where the students discover the acceleration of objects in free fall and learn to calculate the speed and height of a projectile. She thought of the gel Waboba balls because her dog has the pet version - the Waboba Fetch (she has 4, a true furbobian). Noelle knew her students would feel safer trying to catch soft Waboba balls over a hard softball, and others would feel safe with balls flying over their heads too. Plus, they could do the experiment in the gym if needed, and the Pro balls would be heavy enough to get good height, minimizing the effect of air resistance, which would skew their results.

After we sent Noelle some Waboba Pro Balls on the house (we love our teachers), she kept us posted about the experiment and answered some of our other questions too. We hope Noelle's story inspires other teachers to bring Waboba into the classroom to keep life and learning fun!

When/how did you first discover Waboba?

I first discovered Waboba in a small outdoor equipment store in Northport, MI. They sold the Waboba balls that you can bounce across the water and I bought one for my kids, then I later bought the set for dogs. My dog loves that ball, and it’s the only ball she will play with and chase! It’s also the way we get her in the water in the summertime.

How did your students respond to the experiment?

The students enjoyed throwing the Waboba balls as high as possible. They’re amazing because they’re soft but have a good weight to them, so they easily move through the air and can go very high. The students used timers to measure how long the balls were in the air in order to later calculate how high they could throw. Some students were throwing the balls over 50 feet into the air, but there were a few who were almost afraid to throw them and only tossed them about 7 feet high. They had to be encouraged to really throw them!

Any funny stories to share from the lesson?

Any funny stories to share from the lesson?

One of the students threw a ball so high that it went onto the roof of our gym. It’s still there because we don’t have a ladder high enough to get it down!

How is Steiner School different from other schools?

Something that sets Steiner (a Waldorf school) apart is that we work hard to meet students where they are developmentally. This means that in the preschool years the students’ time is primarily spent playing, to develop a healthy imagination, body and senses, as well as doing meaningful and fun work such as cooking and baking. They also hear many stories to foster the formation of mental pictures which later supports reading comprehension. In the lower grades the students transition from a more movement-based curriculum to learning about nature, cultures and sciences primarily through stories to which they connect deeply. The upper grades and high school are where the curriculum shift to more deeply intellectual topics and conversations around culture, literature and the sciences. Throughout our school the students are given a balanced curriculum including subjects lessons, arts, music and movement. Our student-centered approach also cultivates and establishes substantial relationships and helps develop social skills and moral character, as well as, offering a college-prep education.

How do you keep your students engaged in a tech-heavy world?

Something that sets Steiner apart is that we base our science lessons on experiences instead of textbooks or videos. In our science classes, students always start with hands-on experiences. Therefore, the sciences lessons begin in the laboratory and in the field. Observation and experimentation of the phenomena is the basis for the development of the laws and theories of modern science. The result is that we are educating the students to think and discover for themselves, which will serve them particularly well in the sciences but will also be beneficial no matter what their future career will be.

Favorite memory as a teacher:

I love seeing the growth of the students from 9th grade through 12th grade. Students come to us in 9th grade, some with many worries and insecurities and others with an overabundance of confidence. They are often very social but can be lacking in organizational skills, responsibility and social compassion. They grow and change so much from 9th to 12th grade and develop into caring and compassionate young adults.

Favorite memory as a student:

I loved chemistry and physics classes as a student. I remember the day my physics teacher did a demonstration where two balls were simultaneously released from the same height. One was launched horizontally and the other was dropped vertically. I was shocked that they hit the ground at the same time. I really thought the one that was launched horizontally would have taken longer to hit the ground. In retrospect, I would have had a hard time believing my teacher if he told us they would hit the ground at the same time without showing us that demonstration. Instead of focusing on questioning the truth of the statement that they would land at the same time, seeing the demonstration first engaged and interested me, and caused me to focus on questioning why they landed at the same time.

How do you Keep Life Fun with your students?

How do you Keep Life Fun with your students?

Because we start every topic with a demonstration or lab experience, the classes are naturally a lot of fun. The students enjoy hands-on learning. We also have engaging discussions in order to understand the phenomena that we investigate. The students enjoy sharing their thoughts and ideas, and it brings a social component to the lessons that would be absent if I was just lecturing. One day the students sat on scooters and raced through the gym to experience relative velocity. Another day I led them in an organized game of tug of war, an experience which led us to discuss vectors and the idea of equilibrium. There are so many examples of experiences the students have in the sciences, in chemistry, physics and the life sciences, throughout their four years in the high school. In their senior year the students travel to Maine as part of their Zoology lessons. We meet up with students from other Waldorf schools from across the country to study the coastal land and the abundance of life in the tide pools.

Did you have a favorite teacher when you were younger that inspired you to teach?

When I was in high school, I had no inclination to ever teach. I was very shy and wasn’t comfortable being in front of a room. My speech class in college was terrifying. I went to school to be an engineer and worked in the automotive industry for 13 years. Although I enjoyed my co-workers and many aspects of engineering work, I felt drawn to do something more meaningful. I’d had children by that point and had discovered the local Waldorf school. I was impressed by the curriculum and the way it built compassion, interest, imagination and logical thinking. Having spent 13 years in engineering, I could directly see the connections between the skills being built in the school and the skills needed for a successful career in engineering.

What inspired you to teach physics?

In order to truly understand a phenomenon, you have to understand it through your own experience. If someone were to give you a mathematical formula explaining motion, you might be able to understand the math, use it to calculate the position vs time, and even graph the motion. However, in order to truly make sense of the model you’d have to be able to connect it to your own experience. You’d have to be able to visualize the motion of the ball. It would be helpful to connect to your experience of throwing a ball straight up, or as far horizontally as you can. Through your own experience you already know and understand so much more than you realize. By connecting to that experience and then applying the math, you can understand the phenomena and the mathematical model that follows. Starting out of their own experience trains students to use their own experience to support their understanding. It also helps them to develop self-confidence as they realize the inherent knowledge they can tap into if they just take the time to recognize what they already fundamentally know to be true through their own experience. I wanted to teach physics in order to help students realize that they have the capacities to figure things out, and to give them experiences and practice doing so, in order to help them develop interest in the world and confidence in themselves.

Thanks to Noelle for taking the time to answer our questions and for sharing her story with us. We wish we were in her class!

Education for an Unpredictable Future

Teens Feel Ready for College, But Not So Much for Work

A new poll found that 74 percent of high school students think they’ll have a job in 20 years that hasn’t been invented yet. How do schools prepare students for that future? In Waldorf education we focus on helping students develop creativity and problem solving skills, communication, teamwork, and empathy, as well as the ability to take their ideas and put them into practice in the real world. These skills are foundational, and prepare students to successfully navigate the unpredictable and rapidly changing world of work and the diverse paths to higher education.

This piece was originally published by Alyson Klein in Education Week

High schoolers believe that their educational experience is getting them ready for college. But they’re less certain that their coursework is preparing them for the world of work.

That’s one of the big takeaways from surveys published recently by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, a nonprofit philanthropy based in Kansas City, Mo. The survey found that 81 percent of students felt that high school got them “very” or “somewhat” ready for college, compared with just 52 percent who felt it prepared them for the workforce.

“People are coming out of this sort of either-or,” said Aaron North, the vice president of education at the Kauffman Foundation. “You’re going to college, or you’re not. You’re getting a job after high school or you’re not. I think that’s not reflective of the reality of what’s on the other side of that graduation stage for them.”

He expects that, in the future, many students will transfer in and out of the workforce, gaining both educational credentials and on-the-job experience.

The survey also found that students and adults in general expect that technology and computer science jobs will be a major growth industry, with 85 percent of adults and 88 percent of students saying they expect those gigs to be in “much” or at least “somewhat more” in demand in the next decade.

And 74 percent of students think they’ll have a job in 20 years that hasn’t been invented yet.

Students “have only grown up in an age of really accelerated tech evolution,” North said. “I think that’s just the world that they are in. It is a world of creation. It is a world of change.”

‘Practical Connection’ Needed

Overwhelmingly, students, parents, and employers surveyed thought high schoolers would be better off learning how to file their taxes than learning about the Pythagorean theorem. At least 82 percent of parents, students, and employers thought schools should focus more on the 1040-EZ form than on that fundamental concept in geometry.

And 81 percent of students said they thought high school should focus most closely on helping students develop real-world skills such as problem-solving and collaboration rather than focusing so much on specific academic-subject-matter expertise.

“I think what that highlights is this idea that there needs to be this practical connection between what and how you are learning when you’re in school and what happens when you’re not in school,” North said. “So that doesn’t mean it has to be directly related to your everyday life, but it does mean that there could be a balance between things that may be applicable to a very narrow number of fields and things that are highly applicable to your life no matter what field you go into or what path you choose.”

Employers are also more likely to rate employees highly if they have completed an internship in their industry and have technical certifications than if they only have a college degree, the survey found.

But at the same time, 56 percent of employers surveyed felt that someone with only a high school degree would be held back from success in life because of their education. Students were even more convinced of the benefits of college, with 63 percent saying that having only a high school education would be a roadblock to success.

Still, most adults—59 percent of those surveyed—said they can’t connect what they learned in high school to their current jobs. That’s especially true of workers in blue-collar jobs, 61 percent of whom say that their jobs weren’t relevant to their high school educations, compared with 52 percent of white-collar employees.

“Parents who have experienced a noncollege pathway understand that those pathways are viable and they can lead to really good options,” North said. “A huge percentage of our population ends up not getting a college degree. And so there are millions and millions of people out there navigating the nondegree world, without much of a road map, the kind of road map we’ve provided around college. So I think that’s reflective of people who have found that and are understanding that, whether it’s for themselves or for their own kids.”

Old Strategies, New Jobs

Similarly, a separate report released last week by the RAND Corp., found that the needs of the workforce have transformed dramatically thanks to technological changes, globalization, and demographic shifts. But K-12 schools, postsecondary institutions, and job-training organizations are preparing students for jobs using essentially the same set of strategies they’ve been relying on for decades.

At the same time, employers are struggling to find workers with so-called “21st-century skills” such as information synthesis, creativity, problem-solving, communication, and teamwork. Yet the path forward is not easy for workers looking to upgrade their skills because of automation or shifting consumer demands.

“Employers are saying they can’t find employees with the skills they need, and on the other end, you have workers whose jobs have been made less relevant,” said Melanie Zaber, an associate economist at RAND, a nonprofit research organization.

The blame shouldn’t be all on schools, the RAND report emphasizes. Employers and education and job-training institutions don’t do a great job of systematically sharing information with schools that would allow them to better prepare students for the changing needs of the workforce. Plus, funding for K-12 education isn’t equally distributed and often neglects the areas that need strong pre-career training the most.

What also makes progress difficult is that high school principals rarely get to see how their students are doing years after they leave the classroom, Zaber said. “Letting high school principals see what happens when students leave their doors can help inform policy for where the gaps are, where the barriers are, where students are being let down,” she said.

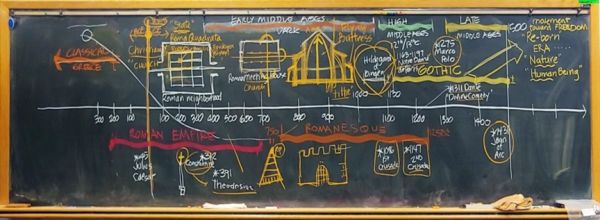

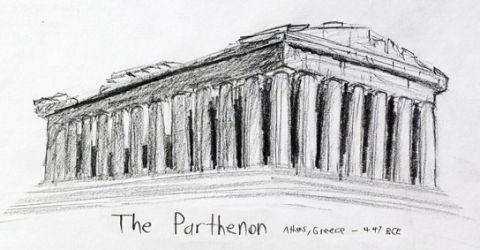

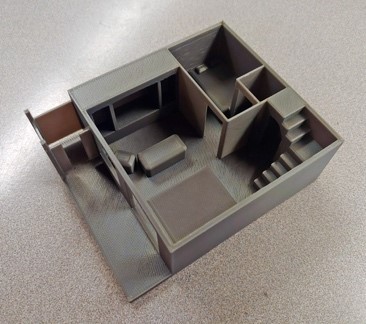

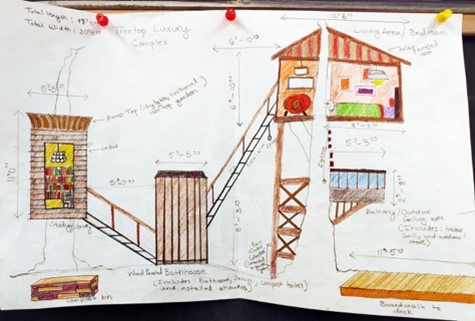

History Through Architecture

History through Architecture is a culminating course in the K-12 journey of Waldorf Education. It is a sweeping survey that traces the development of human consciousness over millennia from the earliest times to the present, including speculations about what the future may hold for our collective lives on Earth. Through this year’s special block, our 12th Graders explored their unique places in the long line of other human beings who have come before them. They began to see themselves with new eyes as they related to the larger human story.

The vehicle for their experience is what we call Architecture…a kind of “memory chip” that holds a rich tapestry of data points logged from all aspects of humanity – iconic facets that have imbued the “bricks-and-mortar” of buildings, cities, landscapes and human-made systems with the zeitgeist or spirit of the age in which they were manifested. Specific teachings in this block have been artfully designed to showcase how human ingenuity advanced with each succeeding generation. New ideas imaginatively evolved to produce structures, materials, energy and metaphysical awareness that created all our structures from simple barrow mounds of earliest human settlements to the soaring skyscrapers of our modern world. All of them imbued with an inner force – a seeking for higher awareness – what we term today a “spiritual experience”.

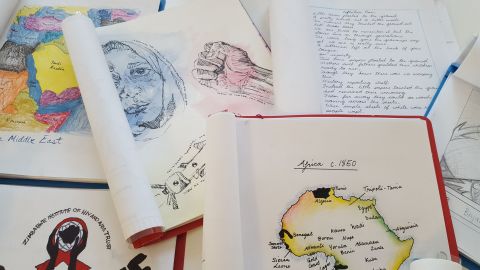

Colorful, hand-drawn chalkboards of chronological, step-by-step timelines showed how passive and dynamic forces of compression and tension moved across time to shape clay, stone, brick, metal, glass and myriad other materials and processes into the infinitely varied forms that we see in our material world. Concepts of “boundary” and “monument” drove the construction of fences, walls for protection from weather and wild animals, but also marked personal identity – whether for an individual or for tribes and clans, where the “I” became a “we”.

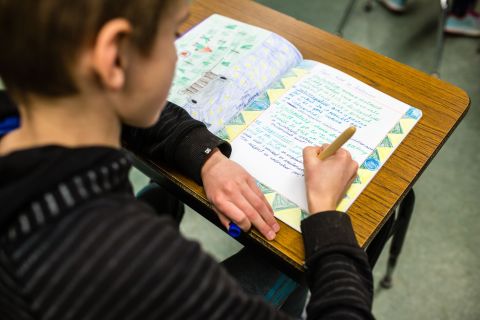

The students hand drew and wrote the salient points of the block into their Main Lesson books. Applying their innate Creativity and Imagination, they recorded the content of their learning. Some exercises were given to demonstrate how historic structures could be shown in plan, section and in three dimensions for learning how buildings are represented.

The students hand drew and wrote the salient points of the block into their Main Lesson books. Applying their innate Creativity and Imagination, they recorded the content of their learning. Some exercises were given to demonstrate how historic structures could be shown in plan, section and in three dimensions for learning how buildings are represented.

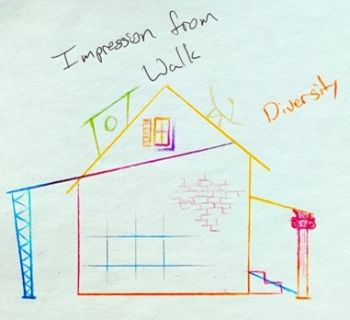

Other exercises engage the students’ personal observations and imaginations. For example, an “Impression/Expression” exercise was assigned for an outside walk taken through the Pontiac Trail neighborhood during one class period. Each student observed a particular perception along the way (a house, a tree, the rhythm of structures, a door or window detail, etc.) that impressed them. Returning to school, some form of expression was made from memory that described the nature of the student’s experience.

Other exercises engage the students’ personal observations and imaginations. For example, an “Impression/Expression” exercise was assigned for an outside walk taken through the Pontiac Trail neighborhood during one class period. Each student observed a particular perception along the way (a house, a tree, the rhythm of structures, a door or window detail, etc.) that impressed them. Returning to school, some form of expression was made from memory that described the nature of the student’s experience.

We contrasted challenging Thinking of the block’s first week with a Clay Handwork exercise that explored the curved line under the force of compression that freed the student’s imagination.

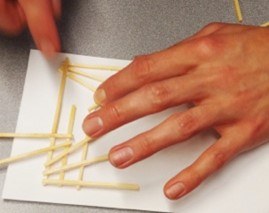

In the second week, Wooden Sticks Handwork created a new experience reflecting the advent of the straight-line forces of tension in history that led to developing open-structured trusses.

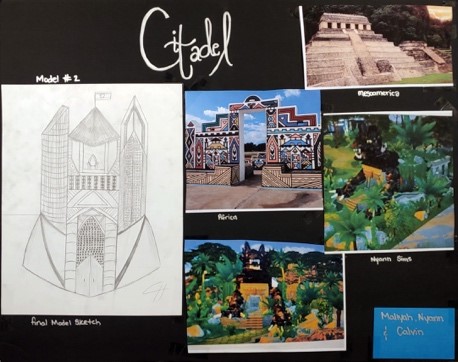

Toward the end of the block, after experiencing the great diversity of human structures built throughout history, students were given a final project where they were asked to design their own “architecture”. The day the assignment was given, this year’s Seniors immediately jumped into action, eagerly discussing possibilities and ideas for their individual or group to develop.

Over several days, students collaborated, talking and sketching ideas until a final design became clear. Every student prepared a statement, drawings, or a model to describe their vision. They then stood before their classmates and presented unique designs which inspired thoughtful questions and comments. This process of inner creativity - manifesting into outer forms -teaches lessons that will serve our Seniors as they venture out into the wider world to pursue their dreams in coming years.

Over several days, students collaborated, talking and sketching ideas until a final design became clear. Every student prepared a statement, drawings, or a model to describe their vision. They then stood before their classmates and presented unique designs which inspired thoughtful questions and comments. This process of inner creativity - manifesting into outer forms -teaches lessons that will serve our Seniors as they venture out into the wider world to pursue their dreams in coming years.

It is a great joy for me to witness the various revelations that unfold through each 12th Grader as they come to know themselves more deeply in the History through Architecture block.

Research Supports the Benefits of Arts Education

Research shows that students who engage in the arts at school perform better in math, reading, and writing, and have an enhanced social and emotional experience. Waldorf education integrates an array of arts into the curriculum to support academic growth, develop communication and collaboration skills, and give children a well-rounded, joyful educational journey!

This article was originally written by Brian Kisida and Daniel H. Bowen and published by the Brookings Institution

A critical challenge for arts education has been a lack of empirical evidence that demonstrates its educational value. Though few would deny that the arts confer intrinsic benefits, advocating “art for art’s sake” has been insufficient for preserving the arts in schools—despite national surveys showing an overwhelming majority of the public agrees that the arts are a necessary part of a well-rounded education.

Over the last few decades, the proportion of students receiving arts education has shrunk drastically. This trend is primarily attributable to the expansion of standardized-test-based accountability, which has pressured schools to focus resources on tested subjects. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets done. These pressures have disproportionately affected access to the arts in a negative way for students from historically underserved communities. For example, a federal government report found that schools designated under No Child Left Behind as needing improvement and schools with higher percentages of minority students were more likely to experience decreases in time spent on arts education.

We recently conducted the first ever large-scale, randomized controlled trial study of a city’s collective efforts to restore arts education through community partnerships and investments. Building on our previous investigations of the impacts of enriching arts field trip experiences, this study examines the effects of a sustained reinvigoration of schoolwide arts education. Specifically, our study focuses on the initial two years of Houston’s Arts Access Initiative and includes 42 elementary and middle schools with over 10,000 third- through eighth-grade students. Our study was made possible by generous support of the Houston Endowment, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Spencer Foundation.

Due to the program’s gradual rollout and oversubscription, we implemented a lottery to randomly assign which schools initially participated. Half of these schools received substantial influxes of funding earmarked to provide students with a vast array of arts educational experiences throughout the school year. Participating schools were required to commit a monetary match to provide arts experiences. Including matched funds from the Houston Endowment, schools in the treatment group had an average of $14.67 annually per student to facilitate and enhance partnerships with arts organizations and institutions. In addition to arts education professional development for school leaders and teachers, students at the 21 treatment schools received, on average, 10 enriching arts educational experiences across dance, music, theater, and visual arts disciplines. Schools partnered with cultural organizations and institutions that provided these arts learning opportunities through before- and after-school programs, field trips, in-school performances from professional artists, and teaching-artist residencies. Principals worked with the Arts Access Initiative director and staff to help guide arts program selections that aligned with their schools’ goals.

Our research efforts were part of a multisector collaboration that united district administrators, cultural organizations and institutions, philanthropists, government officials, and researchers. Collective efforts similar to Houston’s Arts Access Initiative have become increasingly common means for supplementing arts education opportunities through school-community partnerships. Other examples include Boston’s Arts Expansion Initiative, Chicago’s Creative Schools Initiative, and Seattle’s Creative Advantage.

Through our partnership with the Houston Education Research Consortium, we obtained access to student-level demographics, attendance and disciplinary records, and test score achievement, as well as the ability to collect original survey data from all 42 schools on students’ school engagement and social and emotional-related outcomes.

We find that a substantial increase in arts educational experiences has remarkable impacts on students’ academic, social, and emotional outcomes. Relative to students assigned to the control group, treatment school students experienced a 3.6 percentage point reduction in disciplinary infractions, an improvement of 13 percent of a standard deviation in standardized writing scores, and an increase of 8 percent of a standard deviation in their compassion for others. In terms of our measure of compassion for others, students who received more arts education experiences are more interested in how other people feel and more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.

When we restrict our analysis to elementary schools, which comprised 86 percent of the sample and were the primary target of the program, we also find that increases in arts learning positively and significantly affect students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathizing with others. In terms of school engagement, students in the treatment group were more likely to agree that school work is enjoyable, makes them think about things in new ways, and that their school offers programs, classes, and activities that keep them interested in school. We generally did not find evidence to suggest significant impacts on students’ math, reading, or science achievement, attendance, or our other survey outcomes, which we discuss in our full report.

As education policymakers increasingly rely on empirical evidence to guide and justify decisions, advocates struggle to make the case for the preservation and restoration of K-12 arts education. To date, there is a remarkable lack of large-scale experimental studies that investigate the educational impacts of the arts. One problem is that U.S. school systems rarely collect and report basic data that researchers could use to assess students’ access and participation in arts educational programs. Moreover, the most promising outcomes associated with arts education learning objectives extend beyond commonly reported outcomes such as math and reading test scores. There are strong reasons to suspect that engagement in arts education can improve school climate, empower students with a sense of purpose and ownership, and enhance mutual respect for their teachers and peers. Yet, as educators and policymakers have come to recognize the importance of expanding the measures we use to assess educational effectiveness, data measuring social and emotional benefits are not widely collected. Future efforts should continue to expand on the types of measures used to assess educational program and policy effectiveness.

These findings provide strong evidence that arts educational experiences can produce significant positive impacts on academic and social development. Because schools play a pivotal role in cultivating the next generation of citizens and leaders, it is imperative that we reflect on the fundamental purpose of a well-rounded education. This mission is critical in a time of heightened intolerance and pressing threats to our core democratic values. As policymakers begin to collect and value outcome measures beyond test scores, we are likely to further recognize the value of the arts in the fundamental mission of education.

Yes! Field Trips Are Worth The Effort!

Research shows that field trips aren’t just fun and disruptive “extras”; these trips have strong academic and behavioral benefits. A recent study showed that students who went on multiple field trips performed better academically and were less likely to miss school or have behavioral issues than their peers. Waldorf schools value engaging students with the world through hands-on experiences and have specific cultural, community service, and outdoor education trips built into our curriculum to further enrich and enliven our students' education!

This article was originally written by Paige Tutt and published in Edutopia

As a teacher, Elena Aguilar often looked for opportunities to get her students out of the classroom and into different neighborhoods or natural environments. “We did the usual museum trips and science center stuff, but I loved the trips which pushed them into unfamiliar territory,” writes Aguilar, an instructional coach and author. Nudging kids out of their comfort zones, she says, “taught them about others as well as themselves. It helped them see the expansiveness of our world and perhaps inspired them to think about what might be available to them out there.”

Aguilar’s thinking made an impact: 15 years after traveling with her third-grade class to Yosemite National Park, a student contacted Aguilar on Facebook to thank her for the life-changing excursion. “You changed our lives with that trip,” the student wrote. “It's what made me want to be a teacher, to be able to give that same gift to other kids.”

As schools grapple with pandemic-related concerns about balancing in-seat instructional time with non-essentials like trips, new research published in The Journal of Human Resources argues that field trips, and the vital educational experiences that they provide—whether it’s a visit to a local museum or a big commitment like Aguilar’s national park trip—deliver a host of positive social and academic outcomes and are worth the effort.

“The pandemic should not keep schools from providing these essential cultural experiences forever,” asserts Jay P. Greene, one of the study’s co-authors and a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, in an opinion piece for the Daily News. “If schools make culturally-enriching field trips an integral part of the education experience, all students—especially those whose parents have a harder time accessing these experiences on their own—would benefit.”

In the study, researchers assigned more than 1,000 fourth- and fifth-grade students in Atlanta to two groups. One group participated in three to six “culturally-enriching” field trips—visits to an art museum, a live theater performance, and a symphony concert—while students in the control group stayed put in class. The outcome? Kids in the field trip group “scored higher on end-of-grade exams, received higher course grades, were absent less often, and had fewer behavioral infractions,” compared to students in the control group, according to a ScienceDaily brief. Benefits lasted two to three years, Greene writes, and were “most visible when students were in middle school.”

“We are able to demonstrate that a relatively simple intervention—and we consider it pretty low-touch; three field trips in a year, maybe six field trips in two years—can actually have some substantial impacts,” says lead study author Heidi Holmes Erickson in an interview with The 74. “They’re not just limited to social benefits. It shows that smaller interventions can actually have some significant effects on academics as well.”

Field trips aren’t a threat to in-class instruction, Erickson notes, they’re a tool to help bolster engagement and expand students’ horizons. “It's possible to expose students to a broader world and have a culturally enriching curriculum without sacrificing academic outcomes, and it may actually improve academic outcomes,” Erickson says. Far from harming test scores, the researchers found that culturally rich excursions reinforce academics and “students who participated in these field trips were doing better in class.”

Meanwhile, class trips don't need to be elaborate productions to make an impact: small excursions outside the classroom—"low-touch," as the researchers call them—can pack a punch. Here’s how three educators recommend dialing it back with low-stakes options that are both engaging and stimulating for students, but might not require days to prepare and plan:

Make Them Bite-Sized: Instead of allocating an entire day to a field trip, educational consultant Laurel Schwartz takes her classes on micro field trips, or “short outings that can be completed in a single class period.” These real-world encounters, she says, are especially beneficial for English learners and world language students. A micro field trip to a nearby park or around school grounds, for example, can be a great opportunity to “enhance a unit on nature and wildlife while reinforcing vocabulary for senses, colors, and the concepts of quantity and size,” Schwartz writes. “Afterwards, students might write descriptive stories set in the place you visited using vocabulary collected and defined together by the class.”

Try Teacher-Less Trips: To encourage exploration and learning outside of the classroom, former social studies teacher Arch Grieve removes himself from the equation with teacher-less field trips rooted in students’ local communities. Grieve only suggests options that are directly tied to a unit being discussed in class—like attending a talk at a local university or visiting a museum or cultural festival—and offers extra credit to incentivize students. “These trips allow for a greater appreciation of my subject matter than is possible in the school setting, and perhaps best of all, there's little to no planning involved.”

Explore Virtual Options: It may not be as fun as visiting in person, but the Internet makes it possible to visit museums like The National Gallery of London and The Vatican Museums without leaving the school building. Middle school English teacher Laura Bradley likes to search the Museums for Digital Learning website by topic, keyword, and grade level, to find lessons and activities that meet her unique curricular needs. The site grants access to digitized museum collections, 3D models, audio files, documents, images, and videos.

Standing on the Shoulders of Gnomes

When we think of progress, many people refer to the “giants” who propel an organization forward. In reality, it’s all the “gnomes” who do the hard work that makes a community successful. This is certainly the case for Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor. With humble beginnings in a three-room building near Cobblestone Farm in 1980, and eventually a home for our K-8 program on Newport Road, our growing community of inspired parents and teachers had a vision for a full PreK-12 program.

A high school study group was active for many years and eventually, the College of Teachers hired Agaf Dancy in 1996 to spend a year preparing to welcome 22 ninth and tenth graders in the fall. A valiant effort was made by Robert Black, Margot Amrine, Becky Schmitt and Judie Erb to build the high school on the Lower School's Newport Road campus, but there was resistance in the surrounding neighborhood. Judie proposed the Genesis building on Packard Road and Agaf found the ideal faculty team of Mary Emery (Humanities) and Geoff Robb (Science), who were trained Waldorf high school teachers. Navigating precarious waters, Judie, Margot and Fred Amrine won over a reluctant Board and in the fall of 1997, 22 high school students attended classes in the basement of the Genesis building.

Ashlea Walton (HS’ 01) recalls, “It didn’t matter that our classes were small or that we were learning in a basement. Ms. Emery and Mr. Robb, along with the other faculty, made us feel part of a family and the subject areas were enlivened by their enthusiastic approach to teaching.”

Caroline Freitag (HS '02) has known since 7th grade that she would be a Waldorf teacher and is now in her seventeenth-year class teaching, working right here at RSSAA! As one of the pioneering high school students, Caroline didn’t realize initially, “… but I was seeking a high school experience where I was seen by my teachers and peers. These strong personal relationships, along with a wide array of educational opportunities and trips, led me to pursue a college experience that offered the same things.”

Mary and Geoff led an amazing team of supporting faculty including Elena Efimova (Art), Robert Santacroce (Eurythmy), Erica Choberka (Biology), Janice Sanders (Instrumental), Barbara Brown (Bookbinding & Basket-weaving), David Van Eck (Technology) and Margot Amrine (History).

Erica Choberka was a teaching assistant at University of Tennessee, Knoxville and started her high school teaching career at RSSAA. Along with teaching most of the science classes, she briefly taught gym and writing as well - it was all hands-on deck. As a twenty-something herself, she would sometimes hear students listening to “Sublime” on their boombox and resisted the temptation to join them (she was a fan).

Elena Efimova held classes in her home art studio, where students were bussed daily. Her whole house was open to the students - snacks and drinks in the fridge, bathroom in the master bedroom, and a “hotel lobby” in the living room. Some students even stayed for dinner if their parents showed up late. The first senior mosaics (the Five Elements) were created by the first graduating class of five students and now hang in the hallway at the Lower School.

Eventually, we needed more space and in October 2001, a six-acre homestead and factory, located on Pontiac Trail, was purchased to be the permanent home for our growing high school. A staunch group of eager, professional volunteers, who dubbed themselves "The Four Musketeers" (Tim Vachon, Victor Leabu, Robin Grosshuesch and Robert Black) donated both skilled labor and materials to improve the Frame House and the Stone House buildings on the property into administrative spaces. The generous support of key donors, like the Fox family and Erb Downward family and Seyhan Eğe, empowered a whole host of volunteers from families, students, staff and faculty to put the final touches on the former factory building, built by Christman Company and sub-contractor Brivar. The new campus opened in the fall of 2002.

When Evan Schmitt (HS ’01) reflects on his time at RSSAA, “I don’t think a day goes by where I don’t apply the lessons I learned during my time at the Steiner School. So much of my job is talking with organizations about their role in creating a fairer, more secure, and more equitable global economy where individual rights are respected and protected. The seeds of that ethos were planted in me every day I walked into that school…by the teachers, the community, and my fellow students”. As a junior, Evan was key in organizing the first basketball team, coached by Bob Cosey. The sports teams gained momentum, sometimes “borrowing” 8th graders to complete the teams.

In 2008, RSSAA received our largest gift, a bequest of $834,000 from Seyhan Eğe’s estate. This gift paid for a dedicated middle school building in 2016 and launched the Inspire. Create. Lead. Capital Campaign for a high school campus expansion of a gym, lab, classrooms, and performance spaces in 2018, solidifying the commitment to a full PreK-12 Waldorf education.

Although our spaces are beautiful and inspiring, it’s our faculty that make our school an exceptional experience for students and families. A high school parent recognized that during the pandemic, everyone was managing stressful situations and our faculty and staff were doing the same. However, they were also striving to provide the best experience they could for our students along with taking pay cuts to balance the budget. That is devotion.

These stories have reminded us of where we’ve been and how many involved families helped us get there. We are entering the next phase of our development, with seeds being planted to eliminate debt and build an endowment, to create an outstanding Waldorf educational experience that supports our students with outstanding educators, passionate administration, facility maintenance, and financial stability.

Is Travel Good For Teens?

Is it safe? Will they make good choices? What if something happens? Will they meet nice people?