The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

Imagine a typical school day where students, between classes and during breaks, are glued to their smartphones—scrolling through social media, playing games, or texting. Conversations are sparse, eye contact is minimal, and the vibrant energy of youthful interaction seems subdued. Now, contrast this with a school environment where smartphones are set aside: students engage in lively face-to-face discussions, participate in spontaneous games, and immerse themselves fully in classroom activities without the constant pull of notifications. This is the reality we’ve cultivated at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, embracing a phone-free policy that fosters genuine connections and holistic development.

The Deeper Engagement of Phone-Free Education

At our school, we’ve observed that removing smartphones from the school day does more than just eliminate distractions—it rekindles a deeper, more meaningful engagement among students. Freed from screens, students rediscover the joy of direct communication, collaborative problem-solving, and hands-on learning. This environment aligns seamlessly with the principles of Waldorf education, emphasizing experiential learning and nurturing the whole child.

We Are Phone-Free, Not Tech-Free

While our school maintains a phone-free environment during school hours, we are not devoid of technology. In fact, our curriculum incorporates technology in age-appropriate ways to ensure students are prepared for the digital world:

• Middle School: Students are introduced to computers and the internet in an intentional way that supports learning. Additionally, our middle school robotics club fosters interest in technology and engineering through hands-on projects. https://www.steinerschool.org/programs/extracurricular-activities.cfm

• High School: Our state-of-the-art computer lab facilitates courses in coding, digital literacy, and other computer science subjects. We also have an active high school robotics club where students collaborate on competitive projects that develop real-world problem-solving skills. https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-education.cfm

Many of our graduates go on to thrive in technology fields, excelling in computer science, engineering, and data analysis. Research shows that Waldorf graduates develop strong interdisciplinary thinking skills that prepare them for success in fields that require both creativity and technical expertise.

Leading the Way in Ann Arbor

Our commitment to a phone-free school day positions us as pioneers in the Ann Arbor educational community. While some other local schools have implemented partial restrictions, our comprehensive approach ensures that students remain unplugged throughout the day—including breaks and transitions between classes.

Several Ann Arbor schools are recognizing the value of limiting phone use:

• Forsythe Middle School and Tappan Middle School both require students to keep phones in lockers during school hours. https://forsythe.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy, https://tappan.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy

• Huron High School has introduced classroom phone storage policies in its Mathematics and English departments to help students stay focused. https://thehuronemery.com/9731/news/cell-phone-use-teacher-led-procedures-to-enrich-student-experience/

The Transformative Power of Disconnecting

The shift to a phone-free environment has yielded profound benefits:

• Enhanced Academic Focus: Without the allure of smartphones, students engage more deeply in lessons, leading to improved comprehension and retention.

• Strengthened Social Bonds: Face-to-face interactions during breaks and collaborative projects foster authentic relationships and empathy among students.

• Improved Mental Well-being: Reducing screen time has been linked to decreased anxiety and stress, allowing students to be more present and mindful.

Embracing a Connected Future Without Phones

As more schools recognize the value of limiting smartphone use, it’s evident that this movement is not about restricting technology but about reclaiming the essence of human connection and focused learning. By leading the way in this initiative, Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor not only adheres to the foundational principles of Waldorf education but also prepares students for careers in STEM, the arts, and beyond.

We invite families seeking a nurturing, distraction-free educational environment to join us in this journey, where students can truly engage with the world around them and develop into well-rounded individuals.

Explore the experiences of other schools with phone-free policies:

• “New data reveals shocking trend since school mobile phone ban”

- “The big smartphone school experiment”

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/inside-schools-ban-smartphones-6knb8qtfc

- “Cell phones hinder classroom learning. Texas should tell school districts to lock them up”

- "Waldorf Schools are Media Literacy Role Models"

https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-schools-are-media-literacy-role-models/

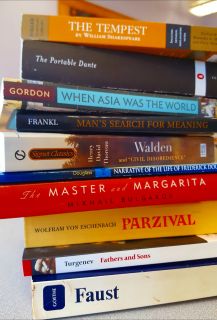

Learning is Multi-Sensory. Teaching Should Be Too.

Children learn in many different ways. That’s why it is so important for teachers to bring concepts through multiple senses. In Waldorf schools we teach science through stories as well as outdoors in nature and in the lab. We move, build, and even bake and eat our math. We teach literature through theater. We sing our history and languages. We teach this way so that our curriculum reaches more children, more deeply, in a way that they love and remember.

This article is an example of the ways the techniques and skills that have always been integral in Waldorf education are being recognized and incorporated into mainstream education.

How Multisensory Activities Enhance Reading Skills

Reading lessons can involve more than just our eyes and ears. Here’s how you can promote reading skills using all five senses.

This article was written by Laura DePriest and originally published on edutopia.org

As educators, we know what it is like to work with children who catch on quickly. The light bulb moments happen fairly easily for them, and they will likely progress despite what we do. We teach them their letter sounds and review flash cards a few times, and from then on those students know and apply them as they learn how to put those sounds together and read.

What can be done for children who are taught those same letter sounds, have seen those same flash cards countless times, and still can’t remember which letter makes which sound? Sometimes those children eventually catch on, but what if they don’t? Often, we assume those children aren’t as smart as the other children. But what if the issue is that their brains are wired in a particular way, and how they are taught needs to be adjusted instead of just repeating the same methods over and over again in the same way?

Recent research has shown that the brain can adapt and make new connections even into old age. Our brains are ever-changing as we take in new information and new experiences. When we discover that a child doesn’t respond to and recall information in the traditional ways, it is important to consider how the brain receives information. The brain is exposed to a stimulus (hearing a phone ring or tasting spaghetti), at which point it analyzes and evaluates the information. Our five senses (sight, touch, hearing, smell, and taste) send information to our brain, which is designed to recognize sensations, initiate behaviors, and store memories.

MULTISENSORY ACTIVITIES REINFORCE STRENGTHS AND IMPROVE WEAKNESSES

So, what does knowing how amazing our brains are mean for us as preschool and early elementary teachers? Well, we can consider very practical ways to incorporate multisensory activities into our literacy instruction. Multisensory activities benefit all students and can be implemented daily in our classrooms. However, the key is to use more than one sense at a time in order to cement the concept. A sight-based activity alone isn’t enough; pair visual learning activities with another type. When a lesson uses multiple senses at once, it reinforces students’ strengths and strengthens their weaknesses.

Sight: Students see stimuli with their eyes. In class, this includes labels on classroom furniture and other items, word walls, anchor charts, or big books. For individual students, it could be flash cards or graphic organizers like Read It, Build It, Write It. With this tool, teachers would dictate or display a word, and students would build the word using letter tiles, and then students would write the word.

Hearing: Students hear stimuli with their ears. This can include hearing letters and letter sounds as you say them, singing rhyming songs, and participating in read-alouds. Shared reading is also a powerful tool for developing literacy. As you read or your students listen to an audiobook, they can interact with the text by underlining sight words or circling the long or short vowels that they hear.

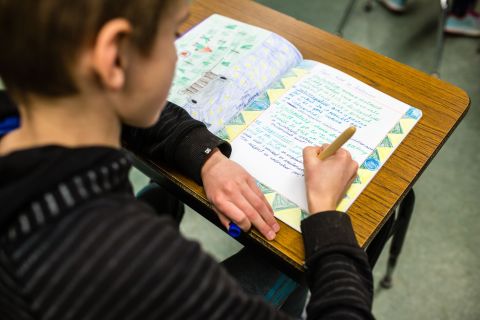

Touch: Students touch stimuli with their hands. This is perhaps the biggest missing piece in our classrooms, but this hands-on approach is crucial for young learners. Students can manipulate letter tiles as they spell words and blend sounds. They can form letters or words with kinetic sand or play-dough, or they can simply trace sandpaper letters with their fingers as they say and hear letter names and sounds.

Air-writing and arm tapping both activate gross motor skills. When air-writing, have your students stand and air-write a word with their dominant arm, moving from their shoulder to promote large muscle movement. When arm-tapping, students tap their arm using their dominant hand from left to right, starting at their shoulder. Saying each sound of the word as they tap reinforces the sounds. Then, have students make a sweeping motion across their arm as they say the whole word, as if underlining it.

The three previously mentioned senses blend seamlessly into the concept of literacy. Smell and taste, however, are much harder to incorporate because they don’t return the same response as knowing letters by sight, sound, and touch/writing. In order for students to best learn the intended literacy skill, the following sensory activities are most effective when they are used with at least one other activity from the previous group.

Smell: Students smell stimuli with their noses. For example, students can form their letters in scented shaving cream or use smelly markers when tracing or writing—perhaps making the letter S with a marker that smells like sweet strawberries. Younger children can read a scratch-and-sniff book, or even make their own book using smelly stickers.

Taste: Students taste stimuli with their mouths. This is the most popular type of activity. You can give students their own portion of letter-shaped crackers, cookies, cereal, or pudding to spell words—they can write letters with their fingers or spell words on crackers using Cheez Whiz. And then, of course, they get to eat their creation.

The best part about multisensory activities is that they usually feel like play to children. But because of what we know about how the brain makes connections and stores memories, these strategies are powerful in helping our children learn how to read. Multisensory literacy activities provide necessary intervention for the students who need it, while making learning more fun for all of our students.

Education in the Age of A.I.

How would you design an education system that helps students flourish in the face of changes to the nature of work brought on by artificial intelligence? The rise of ChatGPT and other AI large-language models have brought this question to the forefront of parents and educators' minds. Waldorf education is uniquely focused on developing children’s creativity, cultural competency, imagination and original thinking. We believe that teaching students to be able to articulate their own diverse viewpoints as well as their understanding of the material sets our students up for future success. In a future where AI-generated content relies on recombining existing work, our graduates' abilities to think critically, divergently, and creatively will serve them well.

ChatGPT Is Dumber Than You Think: Treat it like a toy, not a tool.

This article was originally written by Ian Bogost and published in The Atlantic

As a critic of technology, I must say that the enthusiasm for ChatGPT, a large-language model trained by OpenAI, is misplaced. Although it may be impressive from a technical standpoint, the idea of relying on a machine to have conversations and generate responses raises serious concerns.

First and foremost, ChatGPT lacks the ability to truly understand the complexity of human language and conversation. It is simply trained to generate words based on a given input, but it does not have the ability to truly comprehend the meaning behind those words. This means that any responses it generates are likely to be shallow and lacking in depth and insight.

Furthermore, the reliance on ChatGPT for conversation raises ethical concerns. If people begin to rely on a machine to have conversations for them, it could lead to a loss of genuine human connection. The ability to connect with others through conversation is a fundamental aspect of being human, and outsourcing that to a machine could have detrimental side effects on our society.

Hold up, though. I, Ian Bogost, did not actually write the previous three paragraphs. A friend sent them to me as screenshots from his session with ChatGPT, a program released last week by OpenAI that one interacts with by typing into a chat window. It is, indeed, a large language model (or LLM), a type of deep-learning software that can generate new text once trained on massive amounts of existing written material. My friend’s prompt was this: “Create a critique of enthusiasm for ChatGPT in the style of Ian Bogost.”

ChatGPT wrote more, but I spared you the rest because it was so boring. The AI wrote another paragraph about accountability (“If ChatGPT says or does something inappropriate, who is to blame?”), and then a concluding paragraph that restated the rest (it even began, “In conclusion, …”). In short, it wrote a basic, high-school-style five-paragraph essay.

That fact might comfort or frighten you, depending on your predilections. When OpenAI released ChatGPT to the public last week, the first and most common reaction I saw was fear that it would upend education. “You can no longer give take-home exams,” Kevin Bryan, a University of Toronto professor, posted on Twitter. “I think chat.openai.com may actually spell the end of writing assignments,” wrote Samuel Bagg, a University of South Carolina political scientist. That’s the fear.

But you may find comfort in knowing that the bot’s output, while fluent and persuasive as text, is consistently uninteresting as prose. It’s formulaic in structure, style, and content. John Warner, the author of the book Why They Can’t Write, has been railing against the five-paragraph essay for years and wrote a Twitter thread about how ChatGPT reflects this rules-based, standardized form of writing: “Students were essentially trained to produce imitations of writing,” he tweeted. The AI can generate credible writing, but only because writing, and our expectations for it, has become so unaspiring.

Even pretending to fool the reader by passing off an AI copy as one’s own, like I did above, has become a tired trope, an expected turn in a too-long Twitter thread about the future of generative AI rather than a startling revelation about its capacities. On the one hand, yes, ChatGPT is capable of producing prose that looks convincing. But on the other hand, what it means to be convincing depends on context. The kind of prose you might find engaging and even startling in the context of a generative encounter with an AI suddenly seems just terrible in the context of a professional essay published in a magazine such as The Atlantic. And, as Warner’s comments clarify, the writing you might find persuasive as a teacher (or marketing manager or lawyer or journalist or whatever else) might have been so by virtue of position rather than meaning: The essay was extant and competent; the report was in your inbox on time; the newspaper article communicated apparent facts that you were able to accept or reject.

Perhaps ChatGPT and the technologies that underlie it are less about persuasive writing and more about superb bull**. A bull**er plays with the truth for bad reasons—to get away with something. Initial response to ChatGPT assumes as much: that it is a tool to help people contrive student essays, or news writing, or whatever else. It’s an easy conclusion for those who assume that AI is meant to replace human creativity rather than amend it.

The internet, and the whole technology sector on which it floats, feels like a giant organ for bull**ery—for upscaling human access to speech and for amplifying lies. Online, people cheat and dupe and skirmish with one another. Deep-learning AI worsens all this by hiding the operation of software such as LLMs such that nobody, not even their creators, can explain what they do and why. OpenAI presents its work as context-free and experimental, with no specific use cases—it says it published ChatGPT just to “get users’ feedback and learn about its strengths and weaknesses.” It’s no wonder the first and most obvious assumption to make about ChatGPT is that it is a threat—to something, to everything.

But ChatGPT isn’t a step along the path to an artificial general intelligence that understands all human knowledge and texts; it’s merely an instrument for playing with all that knowledge and all those texts. Play just involves working with raw materials in order to see what they can do. You play a game, or an instrument, to avail yourself of familiar materials in an unexpected way. LLMs are surely not going to replace college or magazines or middle managers. But they do offer those and other domains a new instrument—that’s really the right word for it—with which to play with an unfathomable quantity of textual material.

with human knowledge.

I talked with ChatGPT about a wide range of topics, including poetry, behavioral psychology, and computer programming, in order to test this theory. Right now, ChatGPT is just a tech demo, a research experiment. Less clear is how it might be used, beyond the dire predictions about what sectors its technology might upend. In almost every case, the AI appeared to possess both knowledge and the means to express it. But when pressed—and the chat interface makes it easy to do so—the bot almost always had to admit that it was just making things up.

Sometimes it simply used templates. When I asked ChatGPT to generate a cover letter for a university job, it obliged in a competent but uninspired way. It also produced exactly the same letter for a job as a magazine editor as it did for a job as a cannabis innovator in the Web3 space (“I have a deep understanding of the web3 space and the unique challenges and opportunities it presents”). Fair enough: Most cover letters are terrible, after all, repeating the same trite lines and abstract gestures.

In other cases, the bot produced creative output that was surprisingly synthetic but riddled with flaws. When I asked it to generate an imagist poem in the vein of Ezra Pound or William Carlos Williams about hamburgers, it obliged with this short refrain:

Juicy patty, sizzling hot

Toasted bun, crisp lettuce and tomato

A symphony of flavors, a feast for the senses

Savory, satisfying, a true

American classic.

Not bad, I guess, especially for a computer. But also, the poem is not really an example of imagism, which strives to evoke a precise image by means of deliberate language (something like, “The dense honesty of / A hamburger.”) So I called ChatGPT on it. “This is not an imagist poem.” Its response is worth reproducing in full:

You are correct, the poem that I generated is still not an imagist poem. An imagist poem uses precise, vivid imagery to convey a specific idea or emotion, and focuses on a single image or moment. The poem that I generated uses a more narrative and descriptive style, and does not focus on a single, specific image. It describes the ingredients and flavors of a hamburger, but does not use precise and vivid imagery to convey a specific idea or emotion. I apologize if my previous responses did not meet your expectations, and I will do my best to assist you with any further questions or prompts that you may have.

I also urged the AI to generate a lai (a medieval narrative poem) in the style of Marie de France about the beloved, Texas-based fast-food chain Whataburger. It sure as heck looked a lot like a lai, beginning like this:

In the land of Whataburger, where burgers and fries are king,

A stranger came to visit, and with him brought a ring.

He wore a cloak of velvet, and a hat upon his head,

And he smiled with a twinkle in his eye as he approached the counter, where the burgers are served hot and fresh, and the fries are crispy and golden.

Except for that last line, which is a metrical mess. The AI wasn’t able (or willing) to evaluate its work (“I am a large language model trained by OpenAI and I don’t have the ability to evaluate the quality of literary works or make aesthetic judgments.”), but it was able to tell me about the typical structure of a lai—a short, narrative poem of the 12th century with a particular structure and form, usually written in octosyllabic couplets. The lyrical errors in the generated lai arise from its failure to adhere to that metrical form.

When I asked about the matter, it admitted again that, no, the lai it had written was not structured in octosyllabic couplets, claiming that it had produced “a more modern and playful take on the form of the lai.” I was starting to feel like I was negotiating with a student who had come to office hours to complain about their grade.

This happened over and over again. I asked for source code for an Atari game about scooping cat litter, and the AI sent me valid programming instructions—it understood the assignment—but only disconnected snippets of actual code with the heading comment “This program creates a simple game where the player must use a scoop to pick up their cat’s litters and put them in a trash bin.” It was an icon of the answer I sought rather than the answer itself.

Then I asked for a set of diagnostic criteria for an invented psychological condition I named “Inherited Truculence.” The AI instantly obliged:

Diagnostic Criteria for Inherited Truculence:

A tendency to experience and express aggressive or hostile thoughts and feelings, particularly in response to perceived threats or challenges.

A history of aggressive or hostile behavior, particularly in interpersonal or social situations.

A familial history of aggressive or hostile behavior, indicating a possible genetic or hereditary component to the condition.

Impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning as a result of aggressive or hostile behavior.

The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder or by the effects of a substance (such as drugs or medication).

Except, truculence doesn’t really amount to “aggressive and hostile thoughts and feelings,” does it? I asked, and the AI agreed, eventually revising its diagnostics accordingly at my further prompting (“A tendency to experience and express defiant or confrontational thoughts and feelings,” and so forth).

Likewise, my prompt to offer both an ontological and an epistemological answer to the question When does bread become toast? yielded a generally fluent, seemingly philosophical reply. It read in part: “when we are able to recognize it as toast based on its appearance, texture, and other sensory characteristics.”

But the philosophy of toast is an area of expertise for me, so I was able to discern that this snippet, supposedly an epistemological argument, was really about perception. “Isn’t the second a phenomenal, and not an epistemological argument?” I challenged. And once more, the AI cried uncle without hesitation: “You are correct, the second argument that I provided is a phenomenal, not an epistemological, argument. An epistemological argument focuses on how we come to know or understand something, whereas a phenomenal argument focuses on our experience or perception of something.”

At this point, talking to ChatGPT began to feel like every other interaction one has on the internet, where some guy (always a guy) tries to convert the skim of a Wikipedia article into a case of definitive expertise. Except ChatGPT was always willing to admit that it was wrong. Instantly and without dispute. And in each case, the bot also knew, with reasonable accuracy, why it was wrong. That sounds good but is actually pretty terrible: If one already needs to possess the expertise to identify the problems with LLM-generated text, but the purpose of LLM-generated text is to obviate the need for such knowledge, then we’re in a sour pickle indeed. Maybe it’s time for that paragraph on accountability after all.

But that’s not ChatGPT’s aim. It doesn’t make accurate arguments or express creativity, but instead produces textual material in a form corresponding with the requester’s explicit or implicit intent, which might also contain truth under certain circumstances. That is, alas, an accurate account of textual matter of all kinds: online, in books, on Wikipedia, and well beyond.

Proponents of LLM generativity may brush off this concern. Some will do so by glorifying GPT’s obvious and fully realized genius, in embarrassing ways that I can only bear to link to rather than repeat. Others, more measured but no less bewitched, may claim that “it’s still early days” for a technology a mere few years old but that can already generate reasonably good 12th-century lyric poems about Whataburger. But these are the sentiments of the IT-guy personalities who have most mucked up computational and online life, which is just to say life itself. OpenAI assumes that its work is fated to evolve into an artificial general intelligence—a machine that can do anything. Instead, we should adopt a less ambitious but more likely goal for ChatGPT and its successors: They offer an interface into the textual infinity of digitized life, an otherwise impenetrable space that few humans can use effectively in the present.

To explain what I mean by that, let me show you a quite different exchange I had with ChatGPT, one in which I used it to help me find my way through the textual murk rather than to fool me with its prowess as a wordsmith.

“I’m looking for a specific kind of window covering, but I don’t know what it’s called.” I told the bot. “It’s a kind of blind, I think. What kinds are there?” ChatGPT responded with a litany of window dressings, which was fine. I clarified that I had something in mind that was sort of like a roller blind but made of fabric. “Based on the description you have provided, it sounds like you may be thinking of a roman shade,” it replied, offering more detail and a mini sales pitch for this fenestral technology.

My dearest reader, I do in fact know what a Roman shade is. But lacking that knowledge and nevertheless needing to deploy it in order to make sense of the world—this is exactly the kind of act that is very hard to do with computers today. To accomplish something in the world often boils down to mustering a set of stock materials into the expected linguistic form. That’s true for Google or Amazon, where searches for window coverings or anything else now fail most of the time, requiring time-consuming, tightrope-like finagling to get the machinery to point you in even the general direction of an answer. But it’s also true for student essays, thank-you notes, cover letters, marketing reports, and perhaps even medieval lais (insofar as anyone would aim to create one). We are all faking it with words already. We are drowning in an ocean of content, desperate for form’s life raft.

ChatGPT offers that shape, but—and here’s where the bot did get my position accidentally correct, in part—it doesn’t do so by means of knowledge. The AI doesn’t understand or even compose text. It offers a way to probe text, to play with text, to mold and shape an infinity of prose across a huge variety of domains, including literature and science and shitposting, into structures in which further questions can be asked and, on occasion, answered.

GPT and other large language models are aesthetic instruments rather than epistemological ones. Imagine a weird, unholy synthesizer whose buttons sample textual information, style, and semantics. Such a thing is compelling not because it offers answers in the form of text, but because it makes it possible to play text—all the text, almost—like an instrument.

That outcome could be revelatory! But a huge obstacle stands in the way of achieving it: people, who don’t know what the hell to make of LLMs, ChatGPT, and all the other generative AI systems that have appeared. Their creators haven’t helped, perhaps partly because they don’t know what these things are for either. OpenAI offers no framing for ChatGPT, presenting it as an experiment to help “make AI systems more natural to interact with,” a worthwhile but deeply unambitious goal. Absent further structure, it’s no surprise that ChatGPT’s users frame their own creations as either existential threats or perfected accomplishments. Neither outcome is true, but both are also boring. Imagine worrying about the fate of take-home essay exams, a stupid format that everyone hates but nobody has the courage to kill. But likewise, imagine nitpicking with a computer that just composed something reminiscent of a medieval poem about a burger joint because its lines don’t all have the right meter! Sure, you can take advantage of that opportunity to cheat on school exams or fake your way through your job. That’s what a boring person would do. That’s what a computer would expect.

Computers have never been instruments of reason that can solve matters of human concern; they’re just apparatuses that structure human experience through a very particular, extremely powerful method of symbol manipulation. That makes them aesthetic objects as much as functional ones. GPT and its cousins offer an opportunity to take them up on the offer—to use computers not to carry out tasks but to mess around with the world they have created. Or better: to destroy it.

Research Supports the Benefits of Arts Education

Research shows that students who engage in the arts at school perform better in math, reading, and writing, and have an enhanced social and emotional experience. Waldorf education integrates an array of arts into the curriculum to support academic growth, develop communication and collaboration skills, and give children a well-rounded, joyful educational journey!

This article was originally written by Brian Kisida and Daniel H. Bowen and published by the Brookings Institution

A critical challenge for arts education has been a lack of empirical evidence that demonstrates its educational value. Though few would deny that the arts confer intrinsic benefits, advocating “art for art’s sake” has been insufficient for preserving the arts in schools—despite national surveys showing an overwhelming majority of the public agrees that the arts are a necessary part of a well-rounded education.

Over the last few decades, the proportion of students receiving arts education has shrunk drastically. This trend is primarily attributable to the expansion of standardized-test-based accountability, which has pressured schools to focus resources on tested subjects. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets done. These pressures have disproportionately affected access to the arts in a negative way for students from historically underserved communities. For example, a federal government report found that schools designated under No Child Left Behind as needing improvement and schools with higher percentages of minority students were more likely to experience decreases in time spent on arts education.

We recently conducted the first ever large-scale, randomized controlled trial study of a city’s collective efforts to restore arts education through community partnerships and investments. Building on our previous investigations of the impacts of enriching arts field trip experiences, this study examines the effects of a sustained reinvigoration of schoolwide arts education. Specifically, our study focuses on the initial two years of Houston’s Arts Access Initiative and includes 42 elementary and middle schools with over 10,000 third- through eighth-grade students. Our study was made possible by generous support of the Houston Endowment, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Spencer Foundation.

Due to the program’s gradual rollout and oversubscription, we implemented a lottery to randomly assign which schools initially participated. Half of these schools received substantial influxes of funding earmarked to provide students with a vast array of arts educational experiences throughout the school year. Participating schools were required to commit a monetary match to provide arts experiences. Including matched funds from the Houston Endowment, schools in the treatment group had an average of $14.67 annually per student to facilitate and enhance partnerships with arts organizations and institutions. In addition to arts education professional development for school leaders and teachers, students at the 21 treatment schools received, on average, 10 enriching arts educational experiences across dance, music, theater, and visual arts disciplines. Schools partnered with cultural organizations and institutions that provided these arts learning opportunities through before- and after-school programs, field trips, in-school performances from professional artists, and teaching-artist residencies. Principals worked with the Arts Access Initiative director and staff to help guide arts program selections that aligned with their schools’ goals.

Our research efforts were part of a multisector collaboration that united district administrators, cultural organizations and institutions, philanthropists, government officials, and researchers. Collective efforts similar to Houston’s Arts Access Initiative have become increasingly common means for supplementing arts education opportunities through school-community partnerships. Other examples include Boston’s Arts Expansion Initiative, Chicago’s Creative Schools Initiative, and Seattle’s Creative Advantage.

Through our partnership with the Houston Education Research Consortium, we obtained access to student-level demographics, attendance and disciplinary records, and test score achievement, as well as the ability to collect original survey data from all 42 schools on students’ school engagement and social and emotional-related outcomes.

We find that a substantial increase in arts educational experiences has remarkable impacts on students’ academic, social, and emotional outcomes. Relative to students assigned to the control group, treatment school students experienced a 3.6 percentage point reduction in disciplinary infractions, an improvement of 13 percent of a standard deviation in standardized writing scores, and an increase of 8 percent of a standard deviation in their compassion for others. In terms of our measure of compassion for others, students who received more arts education experiences are more interested in how other people feel and more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.

When we restrict our analysis to elementary schools, which comprised 86 percent of the sample and were the primary target of the program, we also find that increases in arts learning positively and significantly affect students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathizing with others. In terms of school engagement, students in the treatment group were more likely to agree that school work is enjoyable, makes them think about things in new ways, and that their school offers programs, classes, and activities that keep them interested in school. We generally did not find evidence to suggest significant impacts on students’ math, reading, or science achievement, attendance, or our other survey outcomes, which we discuss in our full report.

As education policymakers increasingly rely on empirical evidence to guide and justify decisions, advocates struggle to make the case for the preservation and restoration of K-12 arts education. To date, there is a remarkable lack of large-scale experimental studies that investigate the educational impacts of the arts. One problem is that U.S. school systems rarely collect and report basic data that researchers could use to assess students’ access and participation in arts educational programs. Moreover, the most promising outcomes associated with arts education learning objectives extend beyond commonly reported outcomes such as math and reading test scores. There are strong reasons to suspect that engagement in arts education can improve school climate, empower students with a sense of purpose and ownership, and enhance mutual respect for their teachers and peers. Yet, as educators and policymakers have come to recognize the importance of expanding the measures we use to assess educational effectiveness, data measuring social and emotional benefits are not widely collected. Future efforts should continue to expand on the types of measures used to assess educational program and policy effectiveness.

These findings provide strong evidence that arts educational experiences can produce significant positive impacts on academic and social development. Because schools play a pivotal role in cultivating the next generation of citizens and leaders, it is imperative that we reflect on the fundamental purpose of a well-rounded education. This mission is critical in a time of heightened intolerance and pressing threats to our core democratic values. As policymakers begin to collect and value outcome measures beyond test scores, we are likely to further recognize the value of the arts in the fundamental mission of education.

Arts, Advocacy & Recognition by the Library of Congress

Working to rebuild community and identity in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

Bryan Thao Worra is a talented Laotian American writer, poet and community activist and has forged a path connecting experiences of refugees with the restorative aspects of writing. Born in Vientiane in the Kingdom of Laos, Bryan was adopted at three days old by an American pilot named John Worra, who flew for Royal Air Lao. He arrived in the U.S. six months later and eventually settled with his family in Saline, Michigan. He joined the Rudolf Steiner Lower School in it’s fledgling years (early 1980’s), when the school had mixed grades and only two classrooms. After graduating from 8th grade at RSSAA in 1987, he went on to Saline High School and eventually Otterbein College.

Bryan’s leadership in the writing community is being acknowledged during a livestreamed event at the Library of Congress on May 2 in recognition of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month. Appreciating his accomplishments, we reached out to him in order to learn a little about his thoughts on his Waldorf education and ideas around the arts and advocacy.

Your work over the last 20 years has focused on refugee resettlement and the arts. Can you tell us how you’ve connected with refugees through your writings and Southeast Asian diaspora?

The last two decades have taken me across the globe, searching for others who were scattered in the diaspora that followed the end of the Southeast Asian conflicts of the 20th century. I'd understood that many of the elders who were so fundamental to understanding how and why we are in America were passing away even as the younger generation didn't always know how to ask the questions they needed to preserve their family and community histories. In the United States, and in many parts of the world, those who don't understand their roots are often among the most easily exploited and many will find themselves adrift if they cannot understand who they have been, and how to express a future they see themselves in.

One aspect of my process has involved committing to a range of stories, poems, artworks and presentations on both the historical and the wildly imaginative, the cosmic and the everyday and to encourage my fellow refugees to consider different ways of expressing their own experiences and dreams. To give them the freedom to feel that it's ok to risk and to write more than one story, one poem, one idea to pass on to the next generation.

You joined RSSAA as a very young person. What do you remember about your experience with Waldorf education that has shaped your poetry and writing, or you as a person?

At first it was a startling experience, but a wonderful challenge engaging both my logical and creative sides. Our teachers there helped me find the confidence and initiative to direct my own learning and response to given lessons. One of the most important parts of that experience was creating my own textbooks. That absolutely impacted how I eventually made chapbooks and poetry collections later, and my enthusiasm for having experience on all sides of the publishing process. RSSAA prepared me for high school and college in such a way that I often felt way ahead of my peers and even a little out of place, enthusiastically seeking knowledge and ideas to share with others. It was always surprising to meet others who didn't have that energy and motivation. My years with RSSAA encouraged me to form lifelong friendships and to explore the deep connections between everything and to see my own experiences had a relationship to it all.

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

Growing up there weren't many books about my culture and my heritage in the encyclopedias or in popular culture. There was no clear timeline that helped me understand those essential questions: "Who am I? Where do I come from? Why am I here? Where are we going?" The arts provided a way to risk, and to experiment, to pose questions. They weren't legal depositions, but could often touch on great truths while I explored the questions of my identity and what it might mean to reconnect with others to rebuild our community after the war. Initially this was often a rather non-linear process but it became essential, much like the process in solving a jigsaw puzzle.

Do you have advice for young people who want to pair the arts with advocacy?

There are many ways to articulate a vision for a better world. Sometimes by showing a new model of possibilities, sometimes through warnings of unintended or even intended consequences. Each technique has its uses and limitations, and an artist will always face a particular risk with advocacy: Do we reinforce the existing arguments or dismantle them for something better? Pushback is possible with both. We have to commit to learning as much as we can on a given issue, and then we have to give ourselves permission to risk a new way of expressing what matters to us. And sometimes, an artist must find ways to avoid the inertia that comes from waiting for "the perfect" and instead seek "the good" and "the necessary" at a given point of time. As you get started, the key thing to remember is that you don't need to be the last word, but a word that gets the conversations started to create change.