The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

Imagine a typical school day where students, between classes and during breaks, are glued to their smartphones—scrolling through social media, playing games, or texting. Conversations are sparse, eye contact is minimal, and the vibrant energy of youthful interaction seems subdued. Now, contrast this with a school environment where smartphones are set aside: students engage in lively face-to-face discussions, participate in spontaneous games, and immerse themselves fully in classroom activities without the constant pull of notifications. This is the reality we’ve cultivated at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, embracing a phone-free policy that fosters genuine connections and holistic development.

The Deeper Engagement of Phone-Free Education

At our school, we’ve observed that removing smartphones from the school day does more than just eliminate distractions—it rekindles a deeper, more meaningful engagement among students. Freed from screens, students rediscover the joy of direct communication, collaborative problem-solving, and hands-on learning. This environment aligns seamlessly with the principles of Waldorf education, emphasizing experiential learning and nurturing the whole child.

We Are Phone-Free, Not Tech-Free

While our school maintains a phone-free environment during school hours, we are not devoid of technology. In fact, our curriculum incorporates technology in age-appropriate ways to ensure students are prepared for the digital world:

• Middle School: Students are introduced to computers and the internet in an intentional way that supports learning. Additionally, our middle school robotics club fosters interest in technology and engineering through hands-on projects. https://www.steinerschool.org/programs/extracurricular-activities.cfm

• High School: Our state-of-the-art computer lab facilitates courses in coding, digital literacy, and other computer science subjects. We also have an active high school robotics club where students collaborate on competitive projects that develop real-world problem-solving skills. https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-education.cfm

Many of our graduates go on to thrive in technology fields, excelling in computer science, engineering, and data analysis. Research shows that Waldorf graduates develop strong interdisciplinary thinking skills that prepare them for success in fields that require both creativity and technical expertise.

Leading the Way in Ann Arbor

Our commitment to a phone-free school day positions us as pioneers in the Ann Arbor educational community. While some other local schools have implemented partial restrictions, our comprehensive approach ensures that students remain unplugged throughout the day—including breaks and transitions between classes.

Several Ann Arbor schools are recognizing the value of limiting phone use:

• Forsythe Middle School and Tappan Middle School both require students to keep phones in lockers during school hours. https://forsythe.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy, https://tappan.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy

• Huron High School has introduced classroom phone storage policies in its Mathematics and English departments to help students stay focused. https://thehuronemery.com/9731/news/cell-phone-use-teacher-led-procedures-to-enrich-student-experience/

The Transformative Power of Disconnecting

The shift to a phone-free environment has yielded profound benefits:

• Enhanced Academic Focus: Without the allure of smartphones, students engage more deeply in lessons, leading to improved comprehension and retention.

• Strengthened Social Bonds: Face-to-face interactions during breaks and collaborative projects foster authentic relationships and empathy among students.

• Improved Mental Well-being: Reducing screen time has been linked to decreased anxiety and stress, allowing students to be more present and mindful.

Embracing a Connected Future Without Phones

As more schools recognize the value of limiting smartphone use, it’s evident that this movement is not about restricting technology but about reclaiming the essence of human connection and focused learning. By leading the way in this initiative, Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor not only adheres to the foundational principles of Waldorf education but also prepares students for careers in STEM, the arts, and beyond.

We invite families seeking a nurturing, distraction-free educational environment to join us in this journey, where students can truly engage with the world around them and develop into well-rounded individuals.

Explore the experiences of other schools with phone-free policies:

• “New data reveals shocking trend since school mobile phone ban”

- “The big smartphone school experiment”

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/inside-schools-ban-smartphones-6knb8qtfc

- “Cell phones hinder classroom learning. Texas should tell school districts to lock them up”

- "Waldorf Schools are Media Literacy Role Models"

https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-schools-are-media-literacy-role-models/

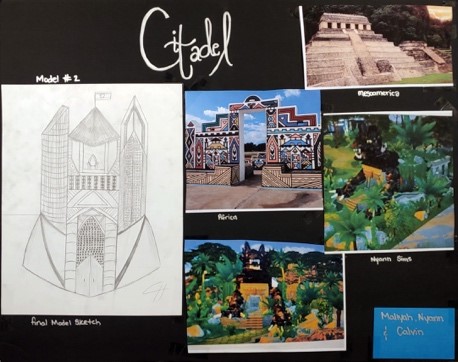

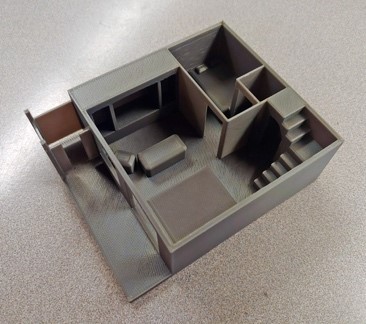

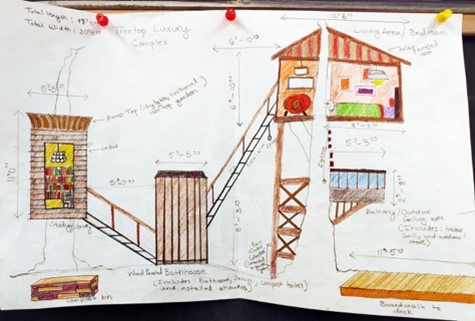

History Through Architecture

History through Architecture is a culminating course in the K-12 journey of Waldorf Education. It is a sweeping survey that traces the development of human consciousness over millennia from the earliest times to the present, including speculations about what the future may hold for our collective lives on Earth. Through this year’s special block, our 12th Graders explored their unique places in the long line of other human beings who have come before them. They began to see themselves with new eyes as they related to the larger human story.

The vehicle for their experience is what we call Architecture…a kind of “memory chip” that holds a rich tapestry of data points logged from all aspects of humanity – iconic facets that have imbued the “bricks-and-mortar” of buildings, cities, landscapes and human-made systems with the zeitgeist or spirit of the age in which they were manifested. Specific teachings in this block have been artfully designed to showcase how human ingenuity advanced with each succeeding generation. New ideas imaginatively evolved to produce structures, materials, energy and metaphysical awareness that created all our structures from simple barrow mounds of earliest human settlements to the soaring skyscrapers of our modern world. All of them imbued with an inner force – a seeking for higher awareness – what we term today a “spiritual experience”.

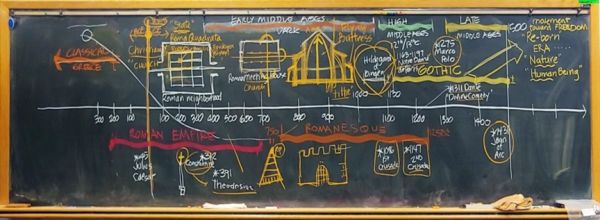

Colorful, hand-drawn chalkboards of chronological, step-by-step timelines showed how passive and dynamic forces of compression and tension moved across time to shape clay, stone, brick, metal, glass and myriad other materials and processes into the infinitely varied forms that we see in our material world. Concepts of “boundary” and “monument” drove the construction of fences, walls for protection from weather and wild animals, but also marked personal identity – whether for an individual or for tribes and clans, where the “I” became a “we”.

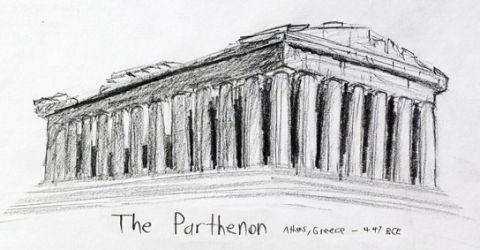

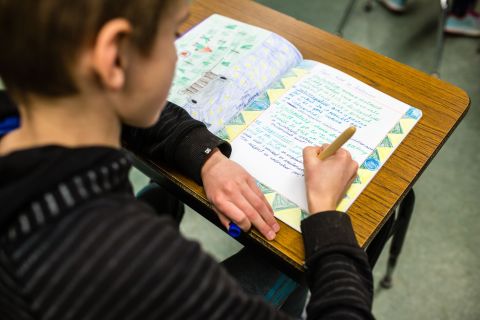

The students hand drew and wrote the salient points of the block into their Main Lesson books. Applying their innate Creativity and Imagination, they recorded the content of their learning. Some exercises were given to demonstrate how historic structures could be shown in plan, section and in three dimensions for learning how buildings are represented.

The students hand drew and wrote the salient points of the block into their Main Lesson books. Applying their innate Creativity and Imagination, they recorded the content of their learning. Some exercises were given to demonstrate how historic structures could be shown in plan, section and in three dimensions for learning how buildings are represented.

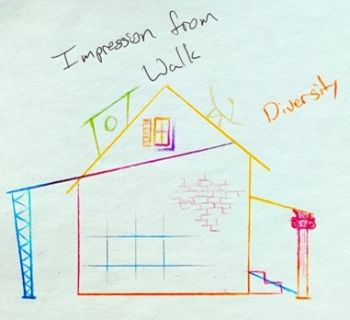

Other exercises engage the students’ personal observations and imaginations. For example, an “Impression/Expression” exercise was assigned for an outside walk taken through the Pontiac Trail neighborhood during one class period. Each student observed a particular perception along the way (a house, a tree, the rhythm of structures, a door or window detail, etc.) that impressed them. Returning to school, some form of expression was made from memory that described the nature of the student’s experience.

Other exercises engage the students’ personal observations and imaginations. For example, an “Impression/Expression” exercise was assigned for an outside walk taken through the Pontiac Trail neighborhood during one class period. Each student observed a particular perception along the way (a house, a tree, the rhythm of structures, a door or window detail, etc.) that impressed them. Returning to school, some form of expression was made from memory that described the nature of the student’s experience.

We contrasted challenging Thinking of the block’s first week with a Clay Handwork exercise that explored the curved line under the force of compression that freed the student’s imagination.

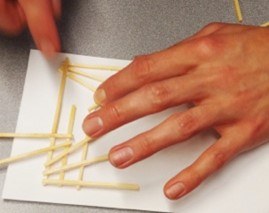

In the second week, Wooden Sticks Handwork created a new experience reflecting the advent of the straight-line forces of tension in history that led to developing open-structured trusses.

Toward the end of the block, after experiencing the great diversity of human structures built throughout history, students were given a final project where they were asked to design their own “architecture”. The day the assignment was given, this year’s Seniors immediately jumped into action, eagerly discussing possibilities and ideas for their individual or group to develop.

Over several days, students collaborated, talking and sketching ideas until a final design became clear. Every student prepared a statement, drawings, or a model to describe their vision. They then stood before their classmates and presented unique designs which inspired thoughtful questions and comments. This process of inner creativity - manifesting into outer forms -teaches lessons that will serve our Seniors as they venture out into the wider world to pursue their dreams in coming years.

Over several days, students collaborated, talking and sketching ideas until a final design became clear. Every student prepared a statement, drawings, or a model to describe their vision. They then stood before their classmates and presented unique designs which inspired thoughtful questions and comments. This process of inner creativity - manifesting into outer forms -teaches lessons that will serve our Seniors as they venture out into the wider world to pursue their dreams in coming years.

It is a great joy for me to witness the various revelations that unfold through each 12th Grader as they come to know themselves more deeply in the History through Architecture block.

Research Supports the Benefits of Arts Education

Research shows that students who engage in the arts at school perform better in math, reading, and writing, and have an enhanced social and emotional experience. Waldorf education integrates an array of arts into the curriculum to support academic growth, develop communication and collaboration skills, and give children a well-rounded, joyful educational journey!

This article was originally written by Brian Kisida and Daniel H. Bowen and published by the Brookings Institution

A critical challenge for arts education has been a lack of empirical evidence that demonstrates its educational value. Though few would deny that the arts confer intrinsic benefits, advocating “art for art’s sake” has been insufficient for preserving the arts in schools—despite national surveys showing an overwhelming majority of the public agrees that the arts are a necessary part of a well-rounded education.

Over the last few decades, the proportion of students receiving arts education has shrunk drastically. This trend is primarily attributable to the expansion of standardized-test-based accountability, which has pressured schools to focus resources on tested subjects. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets done. These pressures have disproportionately affected access to the arts in a negative way for students from historically underserved communities. For example, a federal government report found that schools designated under No Child Left Behind as needing improvement and schools with higher percentages of minority students were more likely to experience decreases in time spent on arts education.

We recently conducted the first ever large-scale, randomized controlled trial study of a city’s collective efforts to restore arts education through community partnerships and investments. Building on our previous investigations of the impacts of enriching arts field trip experiences, this study examines the effects of a sustained reinvigoration of schoolwide arts education. Specifically, our study focuses on the initial two years of Houston’s Arts Access Initiative and includes 42 elementary and middle schools with over 10,000 third- through eighth-grade students. Our study was made possible by generous support of the Houston Endowment, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Spencer Foundation.

Due to the program’s gradual rollout and oversubscription, we implemented a lottery to randomly assign which schools initially participated. Half of these schools received substantial influxes of funding earmarked to provide students with a vast array of arts educational experiences throughout the school year. Participating schools were required to commit a monetary match to provide arts experiences. Including matched funds from the Houston Endowment, schools in the treatment group had an average of $14.67 annually per student to facilitate and enhance partnerships with arts organizations and institutions. In addition to arts education professional development for school leaders and teachers, students at the 21 treatment schools received, on average, 10 enriching arts educational experiences across dance, music, theater, and visual arts disciplines. Schools partnered with cultural organizations and institutions that provided these arts learning opportunities through before- and after-school programs, field trips, in-school performances from professional artists, and teaching-artist residencies. Principals worked with the Arts Access Initiative director and staff to help guide arts program selections that aligned with their schools’ goals.

Our research efforts were part of a multisector collaboration that united district administrators, cultural organizations and institutions, philanthropists, government officials, and researchers. Collective efforts similar to Houston’s Arts Access Initiative have become increasingly common means for supplementing arts education opportunities through school-community partnerships. Other examples include Boston’s Arts Expansion Initiative, Chicago’s Creative Schools Initiative, and Seattle’s Creative Advantage.

Through our partnership with the Houston Education Research Consortium, we obtained access to student-level demographics, attendance and disciplinary records, and test score achievement, as well as the ability to collect original survey data from all 42 schools on students’ school engagement and social and emotional-related outcomes.

We find that a substantial increase in arts educational experiences has remarkable impacts on students’ academic, social, and emotional outcomes. Relative to students assigned to the control group, treatment school students experienced a 3.6 percentage point reduction in disciplinary infractions, an improvement of 13 percent of a standard deviation in standardized writing scores, and an increase of 8 percent of a standard deviation in their compassion for others. In terms of our measure of compassion for others, students who received more arts education experiences are more interested in how other people feel and more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.

When we restrict our analysis to elementary schools, which comprised 86 percent of the sample and were the primary target of the program, we also find that increases in arts learning positively and significantly affect students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathizing with others. In terms of school engagement, students in the treatment group were more likely to agree that school work is enjoyable, makes them think about things in new ways, and that their school offers programs, classes, and activities that keep them interested in school. We generally did not find evidence to suggest significant impacts on students’ math, reading, or science achievement, attendance, or our other survey outcomes, which we discuss in our full report.

As education policymakers increasingly rely on empirical evidence to guide and justify decisions, advocates struggle to make the case for the preservation and restoration of K-12 arts education. To date, there is a remarkable lack of large-scale experimental studies that investigate the educational impacts of the arts. One problem is that U.S. school systems rarely collect and report basic data that researchers could use to assess students’ access and participation in arts educational programs. Moreover, the most promising outcomes associated with arts education learning objectives extend beyond commonly reported outcomes such as math and reading test scores. There are strong reasons to suspect that engagement in arts education can improve school climate, empower students with a sense of purpose and ownership, and enhance mutual respect for their teachers and peers. Yet, as educators and policymakers have come to recognize the importance of expanding the measures we use to assess educational effectiveness, data measuring social and emotional benefits are not widely collected. Future efforts should continue to expand on the types of measures used to assess educational program and policy effectiveness.

These findings provide strong evidence that arts educational experiences can produce significant positive impacts on academic and social development. Because schools play a pivotal role in cultivating the next generation of citizens and leaders, it is imperative that we reflect on the fundamental purpose of a well-rounded education. This mission is critical in a time of heightened intolerance and pressing threats to our core democratic values. As policymakers begin to collect and value outcome measures beyond test scores, we are likely to further recognize the value of the arts in the fundamental mission of education.

A Beautiful Experiment (Italy Part 2)

A beautiful experiment: 17 high school seniors, 5 teachers, and Venice, the floating city. Ms. Efimova, our high school art teacher, had the original idea, an “art trip…with sketchbooks.” After nearly a year of preparation, our plane left Detroit Metro Airport for Venice. It was March, 2001. Twenty trips later, the Italian Journey has become a cherished tradition for the seniors at Rudolf Steiner High School. Spring arrives in Italy, and our Italian friends wait impatiently for us to arrive. They deeply appreciate our students’ joyful laughter, heartfelt curiosity about Italy, thoughtfulness, kindness, singing, and gorgeous drawings. One of our guides has said, “No one on earth travels like this school”. It is true. We are not tourists at all, but thinkers and artists open to the possibility of surprising transformations. In a way, the experiment continues, with amazing results year after year.

No one on earth travels like this school.

Venice, Florence, and Rome are our three muses now, with, when possible, the sweet addition of Orvieto, Lucca, Fiesole, Verona, or Vatican City. We begin in Venice. It is impossible to imagine this most improbable of cities until we sit in the rocking boat which takes us to the main islands of Venice. Arriving by sea has been the custom for about 1500 years. We disembark and the students gasp. “It is unreal!” “The buildings are older than a forest!” “There are no cars, and I hear just the water!” “It is a dream.” The changing colors and the continual movement of the water are mesmerizing, “quasi una fantasia”, almost like a fantasy. That’s the tempo marking for Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”. If you cannot fly to Venice right this moment, try listening to that well-known piece. It will comfort you! This is the city married to the sea, but also the city where Galileo demonstrated his telescope for the Doge from the top of the bell tower. Optics and acoustics. A Scientific Revolution on the way.

Venice, Florence, and Rome are our three muses now, with, when possible, the sweet addition of Orvieto, Lucca, Fiesole, Verona, or Vatican City. We begin in Venice. It is impossible to imagine this most improbable of cities until we sit in the rocking boat which takes us to the main islands of Venice. Arriving by sea has been the custom for about 1500 years. We disembark and the students gasp. “It is unreal!” “The buildings are older than a forest!” “There are no cars, and I hear just the water!” “It is a dream.” The changing colors and the continual movement of the water are mesmerizing, “quasi una fantasia”, almost like a fantasy. That’s the tempo marking for Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”. If you cannot fly to Venice right this moment, try listening to that well-known piece. It will comfort you! This is the city married to the sea, but also the city where Galileo demonstrated his telescope for the Doge from the top of the bell tower. Optics and acoustics. A Scientific Revolution on the way.

Quasi una fantasia.

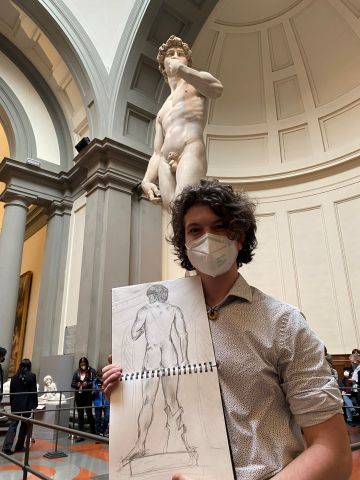

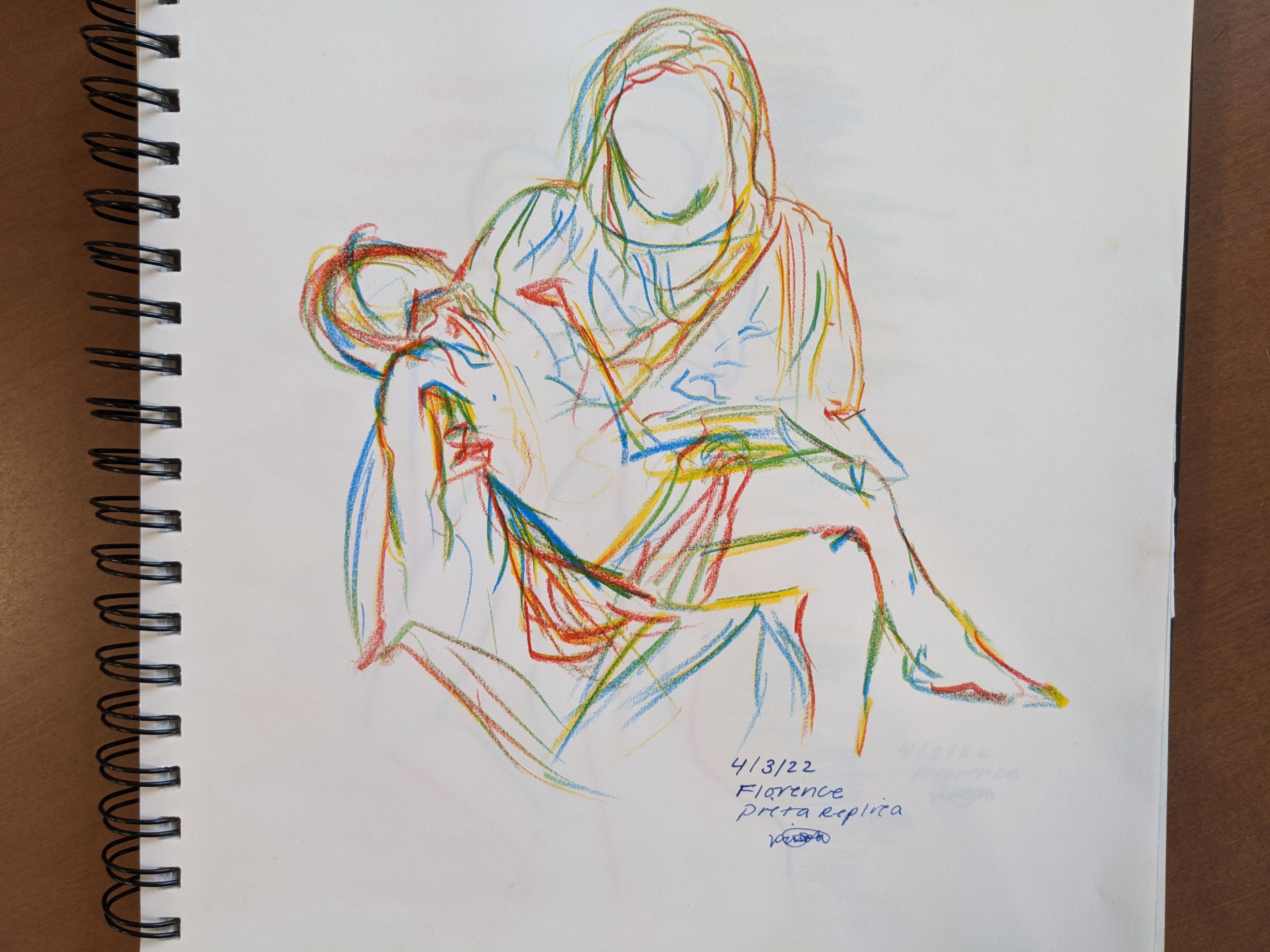

Water gives way to solid ground. We arrive in Florence, a city of prose and poetry, individualism and competition, science and art, dark buildings and sun-drenched courtyards. An Italian proverb states that spring has arrived “when you can step on nine daisies at once.” At the convent that has been our home in Florence these many years, we are greeted by both the nuns, and the garden daisies. Within moments, our students are weaving garlands for their hair. Then to sketch Michelangelo’s “David”! We walk in his footsteps, and Dante’s, and Brunelleschi’s, and Leonardo’s and again, Galileo’s. Academic lessons happens in tiny bursts. Here is the corner where Michelangelo and Leonardo argued, there is Dante’s street, that’s where Botticelli burned his paintings (fortunately not all of them). The intrigue, the excitement, the stupendous discoveries of Renaissance Florentines continue to resound. The cast of characters has changed, but the stage sets are all still there.

Water gives way to solid ground. We arrive in Florence, a city of prose and poetry, individualism and competition, science and art, dark buildings and sun-drenched courtyards. An Italian proverb states that spring has arrived “when you can step on nine daisies at once.” At the convent that has been our home in Florence these many years, we are greeted by both the nuns, and the garden daisies. Within moments, our students are weaving garlands for their hair. Then to sketch Michelangelo’s “David”! We walk in his footsteps, and Dante’s, and Brunelleschi’s, and Leonardo’s and again, Galileo’s. Academic lessons happens in tiny bursts. Here is the corner where Michelangelo and Leonardo argued, there is Dante’s street, that’s where Botticelli burned his paintings (fortunately not all of them). The intrigue, the excitement, the stupendous discoveries of Renaissance Florentines continue to resound. The cast of characters has changed, but the stage sets are all still there.

Grand Finale! Urbs Aeterna: The Eternal City. Rome! The scale is immense. The architecture, in ruins or intact, is magnificent, the vistas are glorious. Mosaic, paint, marble, bronze, gold, and ancient, perfect, concrete compete for our attention. Archeological work is everywhere. After all, 80% of Rome is still buried underground, and someone must dig it up! This city is modern and ancient and medieval and Renaissance and Baroque all at once. How can we make sense of it? Our beloved guide weaves a tapestry of stories while we walk together. She does it so wonderfully that sometimes we cry. Her stories are timed to our steps through the streets. It is her unique form of choreography. Genius, truly. We are enriched and at home. She has given us the keys to the city.

Our Italian Journey comes to a close for another year. Almost 450 students and teachers have traveled to Italy with Rudolf Steiner High School. Every single one has left an imprint. All have strong memories, sketchbooks and a connection with the world and each other that cannot be created in the classroom alone. We're honored to be able to offer this unique experience to our students and grateful to all who have been a part of it. Grazie Mille! Deepest thanks to all who have made this beautiful idea an even more beautiful reality!

Our Italian Journey comes to a close for another year. Almost 450 students and teachers have traveled to Italy with Rudolf Steiner High School. Every single one has left an imprint. All have strong memories, sketchbooks and a connection with the world and each other that cannot be created in the classroom alone. We're honored to be able to offer this unique experience to our students and grateful to all who have been a part of it. Grazie Mille! Deepest thanks to all who have made this beautiful idea an even more beautiful reality!

(We'd like to express our regret to the classes of 2020 and 2021 who, due to the pandemic, were unable to experience Italy in this way.)

Please Enjoy Our YouTube Video

Our Return to Italy (Part 1)

Despite the trepidation we all felt in planning for this trip during the ongoing pandemic, after two years without it we felt more sure than ever about the value of this capstone experience to our senior students, and we charged ahead. It took many months to plan and we had multiple scares with the vagaries of the flight and tour schedules, the worry over possible loss of accommodations due to COVID, and the additional work of verifying and collecting vaccination information and ongoing COVID testing for all students and chaperones, but everything fell into place. Before departing, students had a week and a half of intense preparation where they learned in-depth history and the curriculum context of the places they would visit, as well as some Italian phrases. They also had some time to practice live sketching. The careful planning of the trip - both curricularly and logistically - paved the way for a smooth and enriching experience for all the students.

The trip was seven nights: three in Venice, two in Florence, and two in Rome. Students visited important art and historical sites and were required to capture their trip via drawings and written reflections in their sketchbooks.

Upon their return, each student highlighted a meaningful Italy moment during an all-school assembly, including:

- Being outside of the USA for the first time and experiencing all the differences and surprises

- Going on group night walks in Venice and seeing the difference between the busy day time and serene night time

- Experiencing St. Peters Basilica at the Vatican

- Seeing everything we learned in Art History class up close

- The many androgynous-looking statues beautifully displayed in The Uffizi

- Climbing up the Campanile (belltower) in Florence and seeing how beautiful the city looks

- Walking in the footsteps of the many great artists we learned about in school

- Seeing Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus in real life

- Touring the Roman Forum with our guide, Francesca, and reliving ancient Rome

- The restaurants, convents, and hotels where our school has long standing relationships

We are thrilled that the students were able to have these experiences after the disappointment of the canceled trips in 2020 and 2021. The Italy trip, like all of our school trips, is an opportunity for growth unlike what most students have in their day-to-day classes and extracurricular activities. Our class of 2022 students jumped at the chance to experience another culture, to see different ways of conducting daily life, and to consider a different, and much longer, sense of time through the history around them. Our wish is that they continue to lean in to the curiosity they have developed in high school so that they can keep learning and growing.

Join us for an in-depth look at the trip itself in our next Look A Little Deeper blog post!

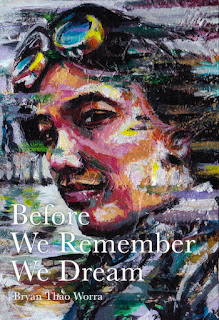

Arts, Advocacy & Recognition by the Library of Congress

Working to rebuild community and identity in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

Bryan Thao Worra is a talented Laotian American writer, poet and community activist and has forged a path connecting experiences of refugees with the restorative aspects of writing. Born in Vientiane in the Kingdom of Laos, Bryan was adopted at three days old by an American pilot named John Worra, who flew for Royal Air Lao. He arrived in the U.S. six months later and eventually settled with his family in Saline, Michigan. He joined the Rudolf Steiner Lower School in it’s fledgling years (early 1980’s), when the school had mixed grades and only two classrooms. After graduating from 8th grade at RSSAA in 1987, he went on to Saline High School and eventually Otterbein College.

Bryan’s leadership in the writing community is being acknowledged during a livestreamed event at the Library of Congress on May 2 in recognition of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month. Appreciating his accomplishments, we reached out to him in order to learn a little about his thoughts on his Waldorf education and ideas around the arts and advocacy.

Your work over the last 20 years has focused on refugee resettlement and the arts. Can you tell us how you’ve connected with refugees through your writings and Southeast Asian diaspora?

The last two decades have taken me across the globe, searching for others who were scattered in the diaspora that followed the end of the Southeast Asian conflicts of the 20th century. I'd understood that many of the elders who were so fundamental to understanding how and why we are in America were passing away even as the younger generation didn't always know how to ask the questions they needed to preserve their family and community histories. In the United States, and in many parts of the world, those who don't understand their roots are often among the most easily exploited and many will find themselves adrift if they cannot understand who they have been, and how to express a future they see themselves in.

One aspect of my process has involved committing to a range of stories, poems, artworks and presentations on both the historical and the wildly imaginative, the cosmic and the everyday and to encourage my fellow refugees to consider different ways of expressing their own experiences and dreams. To give them the freedom to feel that it's ok to risk and to write more than one story, one poem, one idea to pass on to the next generation.

You joined RSSAA as a very young person. What do you remember about your experience with Waldorf education that has shaped your poetry and writing, or you as a person?

At first it was a startling experience, but a wonderful challenge engaging both my logical and creative sides. Our teachers there helped me find the confidence and initiative to direct my own learning and response to given lessons. One of the most important parts of that experience was creating my own textbooks. That absolutely impacted how I eventually made chapbooks and poetry collections later, and my enthusiasm for having experience on all sides of the publishing process. RSSAA prepared me for high school and college in such a way that I often felt way ahead of my peers and even a little out of place, enthusiastically seeking knowledge and ideas to share with others. It was always surprising to meet others who didn't have that energy and motivation. My years with RSSAA encouraged me to form lifelong friendships and to explore the deep connections between everything and to see my own experiences had a relationship to it all.

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

Growing up there weren't many books about my culture and my heritage in the encyclopedias or in popular culture. There was no clear timeline that helped me understand those essential questions: "Who am I? Where do I come from? Why am I here? Where are we going?" The arts provided a way to risk, and to experiment, to pose questions. They weren't legal depositions, but could often touch on great truths while I explored the questions of my identity and what it might mean to reconnect with others to rebuild our community after the war. Initially this was often a rather non-linear process but it became essential, much like the process in solving a jigsaw puzzle.

Do you have advice for young people who want to pair the arts with advocacy?

There are many ways to articulate a vision for a better world. Sometimes by showing a new model of possibilities, sometimes through warnings of unintended or even intended consequences. Each technique has its uses and limitations, and an artist will always face a particular risk with advocacy: Do we reinforce the existing arguments or dismantle them for something better? Pushback is possible with both. We have to commit to learning as much as we can on a given issue, and then we have to give ourselves permission to risk a new way of expressing what matters to us. And sometimes, an artist must find ways to avoid the inertia that comes from waiting for "the perfect" and instead seek "the good" and "the necessary" at a given point of time. As you get started, the key thing to remember is that you don't need to be the last word, but a word that gets the conversations started to create change.

The “Memory, Experience & Imagination in Works of Lao & Hmong American Authors” event will be livestreamed on Monday, May 2 at 6:30 pm EDT. It will be available for viewing afterward in the Library's Events Videos collection.

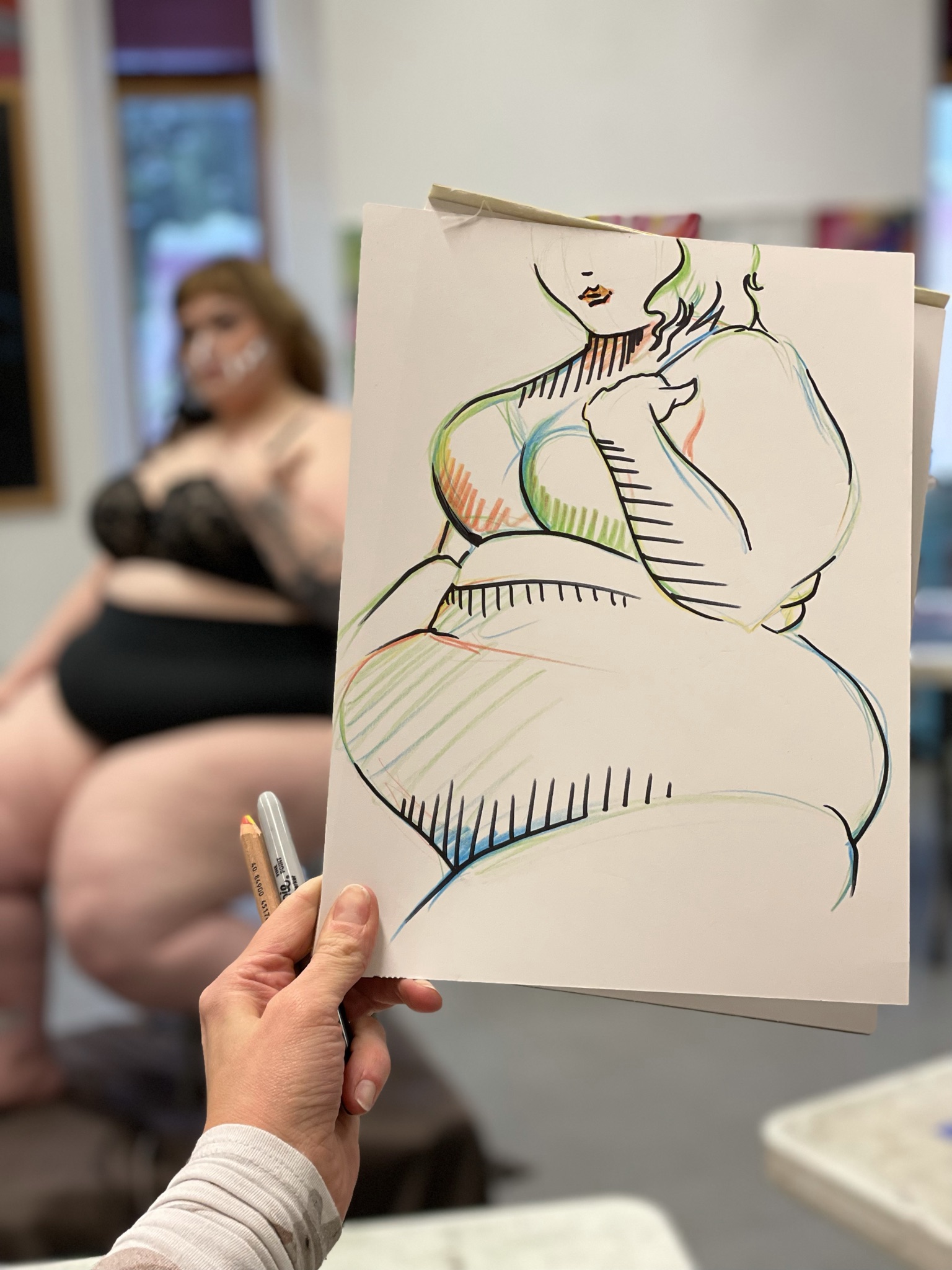

More Than a Body: Capturing the Essence of Another Human

When Elizaveta McFall (HS Art faculty, parent & HS Alum ‘04) began teaching the HS figure-drawing class over four years ago, she

Elizaveta saw an opportunity to re-imagine the approach to this tradition by establishing a dialogue and relationship with the models themselves. She wanted her students to fall in love with people and to see them as art. From her perspective, it is easy to learn the proportions of the human body, but the real work is to capture the model as they are.

She wanted her students to fall in love with people and to see them as art.

In the past, only one model would visit the classroom over a period of several weeks. Now there was an opportunity to open that experience up by inviting multiple models to pose on different days, giving the students a chance to see a variety of human bodies. Her models have evolved from “accepted” male and female body-types to now include a variety of bodies, sizes, gender, and age. This year, she invited a professional wheelchair basketball player who entered the class on his prosthetic legs, talked with the class, then removed his legs and posed for the students in his athletic wheelchair.

Elizaveta wanted to integrate social-emotional learning into the students experience by establishing a relationship with the models during their session. She creates an environment for the models and students to have a conversation. Before the model visits, the students talk about how the model might feel when they arrive - vulnerable, uncomfortable, or nervous. She asks students how do we make them comfortable? Should we giggle (even if it’s not about the model)? Should we ask questions and what kinds of questions? She prepares them to think about “nude” as a genre in art and to look at the model as nude - not naked. Students work through how those terms make them feel.

Before the model visits, the students talk about how the model might feel when they arrive - vulnerable, uncomfortable, or nervous.

Through earlier conversations with the models, Elizaveta learns about their lives, hobbies, jobs or interests. She asks them to think about the shape of their bodies and learns what they are comfortable talking about. This information is then integrated into her class, so she can model the conversation for students, who then begin to pick-up on her approach.

Once the model is back in the room, a comfortable rapport builds as Elizaveta demonstrates for students the questions to ask the models. Nikki, a plus-sized model, is asked about her journey of loving her curvy body. Elizaveta asks the students, “Does Nikki want large paper or small? Do we use straight lines or curved? Where is she most narrow or where is she most broad? What ways can we capture Nikki’s curves?”. It becomes clear that their bodies are aspects of who they are. A trans male model is not introduced by this title but through Elizaveta’s questions, they reveal a favorite part of their transformed body. The conversation with Zeus, a professional wheelchair athlete, reveals how he functions in the sport and how he uses his prosthetics to walk. A pregnant model talks about the temporary body she wears, where she gained weight and the purpose of those changes for the baby.

For students, seeing a body like their own or talking with a trans person or someone with a disability who have fully fallen in love with themselves can be a very powerful experience. Student interests are diverse - from the hard sciences, computers, history, or fine arts - but every high school senior participates in the figure drawing class and is given the opportunity to appreciate the beauty in the diversity of human bodies and interact with the amazing people who inhabit them. Elizaveta knew this new approach would be a unique experience, and the greater impact it would have on our students social-emotional skills and opportunities for growth beyond artistic abilities.

For students, seeing a body like their own or talking with a trans person or someone with a disability who have fully fallen in love with themselves can be a very powerful experience.

The Beautiful Art of Eurythmy

Becoming a Eurythmist

I am Colombian by birth and moved to Michigan with my family at the age of seven. It may surprise you to read that I am a proud alumna of Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor (class of 2004). It is without a doubt the greatest gift of my life that I had the privilege of receiving a Waldorf Education in Ann Arbor. I attended RSSAA starting in the fourth grade. For nearly a decade after graduating from our high school I worked as a freelance musician composing, recording, organizing tours and performing internationally. During my travels across North and South America as well as Europe, I always made a point of visiting as many Waldorf schools as I could.

In my late twenties, I decided to become a Waldorf teacher and found my way to specializing in eurythmy. Since I had studied German as part of RSSAA's rich and broad curriculum, it was no problem for me to complete my four-year eurythmy training in a beautiful school in NW Switzerland, after which I received a master’s degree in Pedagogical Eurythmy from a university in Stuttgart, Germany. Destiny then brought me and my talented Israeli husband (Yoni Paz, full-time humanities teacher at our high school) right back here to Ann Arbor where it is a joy to continue discovering and deepening my love of Waldorf Education. I couldn’t have imagined a more dynamic and rewarding career than this—becoming a eurythmy teacher!

What is Eurythmy?

I ask myself this question all the time. The word “eurythmy” comes from Greek and literally means “beautiful or harmonious movement”. Whether you have had the opportunity to see a live eurythmy performance, taken part in a class, or have never even heard the word before, you may be surprised to learn that this very special movement art form is just in its infancy! Rudolf Steiner and a young German woman by the name of Lory Maier-Smits (a lively 18-year-old who loved gymnastics and dance) started developing eurythmy together in 1911. Thus, we are just entering the second century of eurythmy’s existence. It is slowly blossoming in many forms across the globe.

Today, there are several different applications of eurythmy that have been developed. This was Rudolf Steiner’s hope! He told the early eurythmists that as they helped develop eurythmy they were all planting seeds that wished to sprout and take many forms for serving and inspiring humanity in the future. The main branches of eurythmy alive and in practice currently are:

- Artistic Eurythmy: performed by professional troupes internationally such as New York’s Eurythmy Spring Valley Ensemble: http://www.eurythmy.org/photo-gallery/

- Therapeutic Eurythmy: an unique and effective therapy modality that is practiced in hospitals, clinics, special education centers, schools and private medical offices in many different countries as a form of treatment for a wide variety of conditions including cancer, depression, digestive issues, teeth and vision corrections, and much more. Here is a link to a helpful article: Spoken and Unspoken Gems of Eurythmy Therapy Dale Robinson, Eurythmy Therapist

- Eurythmy in the Workplace and as a Social Art: an application of eurythmy created to enhance productivity, efficiency, awareness, focus, creativity, resilience, communication strategies, team-building and many other skills for individuals and organizations in professional work environments. https://www.leonorerussell.com/eurythmy/

- Pedagogical Eurythmy: eurythmy specialized in supporting the healthy development and learning processes of children and adolescents at Waldorf Schools all around the world.

Pedagogical Eurythmy

I will give a brief picture of pedagogical eurythmy from my perspective. Eurythmy lessons at school are a jewel of the Waldorf curriculum. Ideally, all Waldorf students - from preschool through 12th grade - would have eurythmy every week, all year long (though this is hard to achieve as the number of Waldorf schools far exceeds the number of trained eurythmists!). These lessons are a time when each student gets to be engaged directly and holistically through graceful, meaningful movement to music, poetry, stories, and geometry.

Eurythmy is often defined as “visible speech and visible music”. There are specific arm, leg, head, and full body gestures that express the different sounds of language, aspects of grammar, and parts of music (tones, chords, intervals, rests, etc.). Waldorf students get to learn many of these gestures along with ways of expressing language and music through group choreographies and exercises.

Eurythmy teachers strive to weave the different aspects of their lessons together in artistic and developmentally appropriate ways. The goal is always to support each child’s physical, soul, and spiritual growth in ways that are healthy and inspiring. On the physical level, they learn new gross and fine motor skills, to strengthen their sense of balance, coordination, and agility. Their souls are touched and expanded by the social and creative nature of the eurythmical activities. As they deepen and refine their awareness of and relationships to music and language, the students are provided with opportunities to experience some of the most beautiful forms of human expression we are capable of—ones that define our very human essence, that raise us to our divine spark.

A strong, basic pedagogical eurythmy curriculum for each of the grades has been developed across many countries, in many languages, and is constantly being expanded. It is often referred to as “the heart” of a Waldorf school, as it has a unique and potent ability to harmonize classes on many levels (socially as well as academically). Having eurythmy throughout the years provides students with an orientation in space and time that they create in themselves. This is empowering—it brings a sense of confidence and security in the world.

Eurythmy lessons are meant to be fun, but they are also hard work! For some students it is among the favorite subjects during the week. Other students may complain about eurythmy or claim they dislike it in varying phases of their time at school. This is especially common during adolescence when many are going through great physical changes that can cause them to experience movement as more physically cumbersome than before, while their sense of being watched or feeling exposed is also heightened.

I think both the enjoyment and the struggles students of all ages experience while doing eurythmy arise because eurythmy is very demanding. It can be extremely challenging to refine one’s physical coordination, spatial awareness, musicality, and connection to language SIMULTANEOUSLY! Not to mention, it requires students to work on all of these skills individually as well as collaboratively and cooperatively as part of a group. All of this is precisely what we eurythmy teachers require our students to do and it is a tall order. It is always my hope that each student and each class as a group will be pushed to their growing edge through their eurythmy lessons with me, which I expect to come with its awkward moments as well as well-earned experiences of satisfaction and joy.

In some Waldorf schools in Europe, high school students are required to dedicate a whole semester’s eurythmy lesson time to choreographing, costuming, and performing a eurythmy solo (using all the skills they learned in the years leading up to this) in order to graduate! There are also wonderful traditions in many countries of having older classes create colorful, musical eurythmy performances of fairy or folk tales for the children in younger grades and for school families. I look forward to creating eurythmy traditions of these kinds at our school with time.

Eurythmy at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor

A unique aspect of our eurythmy program at RSSAA is a growing number of collaborations between me and the high school main lesson teachers. We have designed eurythmy lessons as an enhancement of the science and humanities main lesson curriculum for our 9th-12th graders. These eurythmy-main lesson collaborations have taken place in blocks such as Biochemistry, Cell Biology, Astronomy, Embryology, Zoology and Evolution, Botany and Insects, Art History, Parzival, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and Projective Geometry. My goal has been to provide our high school students with ways of artistically and physically moving key elements of their academic subjects. In other words, I strive to translate some of the quintessential aspects of the academic material they study into eurythmy forms and exercises to provide visual, kinesthetic, and collaborative modes of diving into their course material. This has proven itself to be a fun and successful new development of our high school and I am very excited to continue expanding it with my talented colleagues. My master’s thesis describes some of these collaborations and I am hopeful that a book version of it will be published sometime in 2022.

I welcome your questions (apaz@steinerschool.org) and look forward to gradually growing a robust and unique eurythmy program at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor over the years to come!

Village Talkies, a top-quality professional corporate video production company in Dubai and also the best explainer video company in Dubai, 2D animation video makers in Dubai, 3D animation studio in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, UAE, India, and Houston, Dallas, Texas, provides 2D, 3D animation videos, corporate films, event, marketing, safety animation videos, and training videos. As the best 3D animation agency in Dubai and 2d animation company in Dubai, product video makers in Abu Dhabi, we also offer 2D, 3D cartoon & character animations, healthcare and medical videos, CGI, VFX, kids nursery animations, whiteboard explainer videos, and more for all start-ups, industries, and corporate companies. From scripting to corporate, explainer & 3D, 2D animation video production, our solutions are customized to your budget, timeline, and company goals and objectives.