Waldorf Graduates Pursue Meaningful Careers

Will My Child Succeed After Waldorf High School? The Research Says Yes

Choosing a high school is a critical decision, and parents often wonder: Will this education prepare my child for college, career, and life?

For families considering Waldorf high schools, this question is especially relevant. With experiential learning, seminar-style discussions, and an interdisciplinary curriculum, can Waldorf truly equip students for fields like medicine, law, technology, and business?

Decades of research say yes.

Waldorf Graduates Excel in Higher Education and Careers

A 60-year study (Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II, Mitchell & Gerwin, 2007) found that:

- 94% of Waldorf graduates attend college.

- 42% major in science-related fields—more than double the national average.

- Many earn advanced degrees in medicine, law, engineering, business, and the arts.

- Alumni thrive in fields ranging from finance and research to entrepreneurship and sustainability.

Waldorf Alumni Spotlight: Science in Action

After earning a degree in Earth Systems Engineering from the University of Michigan, Gavin Chensue ('06) joined the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps, leading critical climate studies worldwide.

"Steiner education gave me a taste of everything. When I needed direction in college, I remembered how much I loved studying weather and geology—and that led me to where I am today." - Gavin Chensue (RSSAA '06), Research Engineer at SRI International, Former NOAA Corps Officer

His story highlights how Waldorf graduates succeed in STEM, combining curiosity and real-world problem-solving to make a global impact.

Read the full studies:

- Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/research

- Into the World Study: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/graduate-outcomes

What Makes a Waldorf Education So Effective?

Contrary to the belief that test-driven education leads to success, research shows that employers and universities highly value graduates who:

✔ Think critically and independently

✔ Communicate clearly and persuasively

✔ Collaborate effectively

✔ Solve complex problems

✔ Adapt to a changing world

These are precisely the skills Waldorf high schools cultivate.

1. Depth Over Memorization: Lifelong Knowledge Retention

Rather than rote memorization, Waldorf fosters deep understanding:

- History is explored through primary sources and narratives.

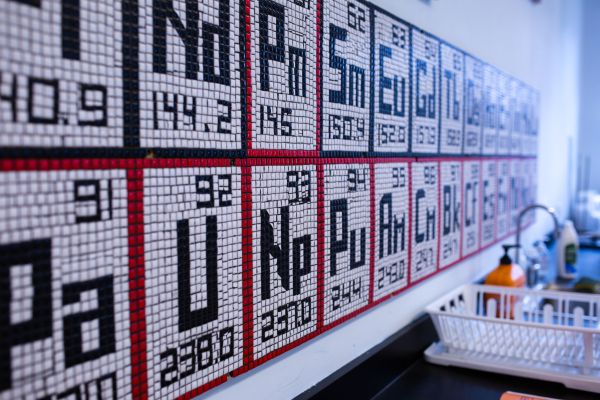

- Science emphasizes hands-on experiments and independent research.

- Mathematics focuses on real-world application.

- Literature and philosophy encourage analytical discussions.

One employer noted:

“Waldorf students don’t just look for the right answer—they explore the why and how behind complex issues.”

2. Seminar-Style Learning Develops Exceptional Communicators

Waldorf emphasizes oral presentations, debates, and collaborative discussions, preparing graduates for leadership roles in law, finance, business, and medicine.

Dr. Ilan Safit, co-author of *Into the World*, states:

“We consistently hear that Waldorf graduates excel at teamwork and leadership. Their ability to articulate complex ideas is a major asset.”

A study from Da Vinci Waldorf School found that Waldorf students select careers based on values and passion rather than prestige or income.

Final Thoughts: The Research Speaks for Itself

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Read more on Waldorf Graduates

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

Imagine a typical school day where students, between classes and during breaks, are glued to their smartphones—scrolling through social media, playing games, or texting. Conversations are sparse, eye contact is minimal, and the vibrant energy of youthful interaction seems subdued. Now, contrast this with a school environment where smartphones are set aside: students engage in lively face-to-face discussions, participate in spontaneous games, and immerse themselves fully in classroom activities without the constant pull of notifications. This is the reality we’ve cultivated at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, embracing a phone-free policy that fosters genuine connections and holistic development.

The Deeper Engagement of Phone-Free Education

At our school, we’ve observed that removing smartphones from the school day does more than just eliminate distractions—it rekindles a deeper, more meaningful engagement among students. Freed from screens, students rediscover the joy of direct communication, collaborative problem-solving, and hands-on learning. This environment aligns seamlessly with the principles of Waldorf education, emphasizing experiential learning and nurturing the whole child.

We Are Phone-Free, Not Tech-Free

While our school maintains a phone-free environment during school hours, we are not devoid of technology. In fact, our curriculum incorporates technology in age-appropriate ways to ensure students are prepared for the digital world:

• Middle School: Students are introduced to computers and the internet in an intentional way that supports learning. Additionally, our middle school robotics club fosters interest in technology and engineering through hands-on projects. https://www.steinerschool.org/programs/extracurricular-activities.cfm

• High School: Our state-of-the-art computer lab facilitates courses in coding, digital literacy, and other computer science subjects. We also have an active high school robotics club where students collaborate on competitive projects that develop real-world problem-solving skills. https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-education.cfm

Many of our graduates go on to thrive in technology fields, excelling in computer science, engineering, and data analysis. Research shows that Waldorf graduates develop strong interdisciplinary thinking skills that prepare them for success in fields that require both creativity and technical expertise.

Leading the Way in Ann Arbor

Our commitment to a phone-free school day positions us as pioneers in the Ann Arbor educational community. While some other local schools have implemented partial restrictions, our comprehensive approach ensures that students remain unplugged throughout the day—including breaks and transitions between classes.

Several Ann Arbor schools are recognizing the value of limiting phone use:

• Forsythe Middle School and Tappan Middle School both require students to keep phones in lockers during school hours. https://forsythe.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy, https://tappan.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy

• Huron High School has introduced classroom phone storage policies in its Mathematics and English departments to help students stay focused. https://thehuronemery.com/9731/news/cell-phone-use-teacher-led-procedures-to-enrich-student-experience/

The Transformative Power of Disconnecting

The shift to a phone-free environment has yielded profound benefits:

• Enhanced Academic Focus: Without the allure of smartphones, students engage more deeply in lessons, leading to improved comprehension and retention.

• Strengthened Social Bonds: Face-to-face interactions during breaks and collaborative projects foster authentic relationships and empathy among students.

• Improved Mental Well-being: Reducing screen time has been linked to decreased anxiety and stress, allowing students to be more present and mindful.

Embracing a Connected Future Without Phones

As more schools recognize the value of limiting smartphone use, it’s evident that this movement is not about restricting technology but about reclaiming the essence of human connection and focused learning. By leading the way in this initiative, Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor not only adheres to the foundational principles of Waldorf education but also prepares students for careers in STEM, the arts, and beyond.

We invite families seeking a nurturing, distraction-free educational environment to join us in this journey, where students can truly engage with the world around them and develop into well-rounded individuals.

Explore the experiences of other schools with phone-free policies:

• “New data reveals shocking trend since school mobile phone ban”

- “The big smartphone school experiment”

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/inside-schools-ban-smartphones-6knb8qtfc

- “Cell phones hinder classroom learning. Texas should tell school districts to lock them up”

- "Waldorf Schools are Media Literacy Role Models"

https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-schools-are-media-literacy-role-models/

Pushing Academics into Preschool Can Be Harmful

A comprehensive study finds significant drawbacks to pushing academics as early as in preschool. Researchers found that any initial academic gains were quickly erased, and children who attended academic-focused Pre-K were actually behind their peers in elementary and middle school. Another troubling finding was that students who experienced early academic pressure showed dramatic increases in behavioral issues later on. In Waldorf education, we focus on what is developmentally appropriate for each age group, understanding that preschool-age children especially need play, movement, and art, which are all critical to social-emotional health and future academic success.

This article was originally published by Anya Kamenetz on NPR.org

A top researcher says it's time to rethink our entire approach to preschool

Dale Farran has been studying early childhood education for half a century. Yet her most recent scientific publication has made her question everything she thought she knew.

"It really has required a lot of soul-searching, a lot of reading of the literature to try to think of what were plausible reasons that might account for this."

And by "this," she means the outcome of a study that lasted more than a decade. It included 2,990 low-income children in Tennessee who applied to free, public prekindergarten programs. Some were admitted by lottery, and the others were rejected, creating the closest thing you can get in the real world to a randomized, controlled trial — the gold standard in showing causality in science.

Farran and her co-authors at Vanderbilt University followed both groups of children all the way through sixth grade. At the end of their first year, the kids who went to pre-K scored higher on school readiness — as expected.

But after third grade, they were doing worse than the control group. And at the end of sixth grade, they were doing even worse. They had lower test scores, were more likely to be in special education, and were more likely to get into trouble in school, including serious trouble like suspensions.

"Whereas in third grade we saw negative effects on one of the three state achievement tests, in sixth grade we saw it on all three — math, science and reading," says Farran. "In third grade, where we had seen effects on one type of suspension, which is minor violations, by sixth grade we're seeing it on both types of suspensions, both major and minor."

That's right. A statewide public pre-K program, taught by licensed teachers, housed in public schools, had a measurable and statistically significant negative effect on the children in this study.

Farran hadn't expected it. She didn't like it. But her study design was unusually strong, so she couldn't easily explain it away.

"This is still the only randomized controlled trial of a statewide pre-K, and I know that people get upset about this and don't want it to be true."

Why it's a bad time for bad news

It's a bad time for early childhood advocates to get bad news about public pre-K. Federally funded universal prekindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds has been a cornerstone of President Biden's social agenda, and there are talks about resurrecting it from the stalled-out "Build Back Better" plan. Preschool has been expanding in recent years and is currently publicly funded to some extent in 46 states. About 7 in 10 4-year-olds now attend some kind of academic program.

This enthusiasm has rested in part on research going back to the 1970s. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman, among others, showed substantial long-term returns on investment for specially designed and carefully implemented programs.

To put it crudely, policymakers and experts have touted for decades now that if you give a 4-year-old who is growing up in poverty a good dose of story time and block play, they'll be more likely to grow up to become a high-earning, productive citizen.

What went wrong in Tennessee

No study is the last word. The research on pre-K continues to be mixed. In May 2021, a working paper (not yet peer reviewed) came out that looked at Boston's pre-K program. The study was a similar size to Farran's, used a similar quasi-experimental design based on random assignment, and also followed up with students for years. This study found that the preschool kids had better disciplinary records and were much more likely to graduate from high school, take the SATs and go to college, though their test scores didn't show a difference.

Farran believes that, with a citywide program, there's more opportunity for quality control than in her statewide study. Boston's program spent more per student, and it also was mixed-income, whereas Tennessee's program is for low-income kids only.

So what went wrong in Tennessee? Farran has some ideas — and they challenge almost everything about how we do school. How teachers are prepared, how programs are funded and where they are located. Even something as simple as where the bathrooms are.

In short, Farran is rethinking her own preconceptions, which are an entire field's preconceptions, about what constitutes quality pre-K.

Do kids in poverty deserve the same teaching as rich kids?

"One of the biases that I hadn't examined in myself is the idea that poor children need a different sort of preparation from children of higher-income families."

She's talking about drilling kids on basic skills. Worksheets for tracing letters and numbers. A teacher giving 10-minute lectures to a whole class of 25 kids who are expected to sit on their hands and listen, only five of whom may be paying any attention.

"Higher-income families are not choosing this kind of preparation," she explains. "And why would we assume that we need to train children of lower-income families earlier?"

Farran points out that families of means tend to choose play-based preschool programs with art, movement, music and nature. Children are asked open-ended questions, and they are listened to.

This is not what Farran is seeing in classrooms full of kids in poverty, where "teachers talk a lot, but they seldom listen to children." She thinks that part of the problem is that teachers in many states are certified for teaching students in prekindergarten through grade 5, or sometimes even pre-K-8. Very little of their training focuses on the youngest learners.

So another major bias that she's challenging is the idea that teacher certification equals quality. "There have been three very large studies, the latest one in 2018, which are not showing any relationship between quality and licensure."

Putting a bubble in your mouth

In 2016, Farran published a study based on her observations of publicly funded Tennessee pre-K classrooms similar to those included in this paper. She found then that the largest chunk of the day was spent in transition time. This means simply moving kids around the building.

Partly this is an architectural problem. Private preschools, even home-based day cares, tend to be laid out with little bodies in mind. There are bathrooms just off the classrooms. Children eat in, or very near, the classroom, too. And there is outdoor play space nearby with equipment suitable for short people.

Putting these same programs in public schools can make the whole day more inconvenient.

"So if you're in an older elementary school, the bathroom is going to be down the hall. You've got to take your children out, line them up and then they wait," Farran says. "And then, if you have to use the cafeteria, it's the same thing. You have to walk through the halls, you know: 'Don't touch your neighbor, don't touch the wall, put a bubble in your mouth because you have to be quiet.' "

One of Farran's most intriguing conjectures is that this need for control could explain the extra discipline problems seen later on in her most recent study.

"I think children are not learning internal control. And if anything, they're learning sort of an almost allergic reaction to the amount of external control that they're having, that they're having to experience in school."

In other words, regularly reprimanding kids for doing normal kid stuff at 4 years old, even suspending them, could backfire down the road as children experience school as a place of unreasonable expectations.

We know from other research that the control of children's bodies at school can have disparate racial impact. Other studies have suggested that Black children are disciplined more often in preschool, as they are in later grades. Farran's study, where 70% of the kids were white, found interactions between race, gender, and discipline problems, but no extra effect of attending preschool was detected.

Where to go from here

The United States has a child care crisis that COVID-19 both intensified and highlighted. Progressive policymakers and advocates have tried for years to expand public support for child care by "pushing it down" from the existing public school system, using the teachers and the buildings.

Farran praises the direction that New York City, for one, has taken instead: a "mixed-delivery" program with slots for 3- and 4-year-olds. Some kids attend free public preschool in existing nonprofit day care centers, some in Head Start programs and some in traditional schools.

But the biggest lesson Farran has drawn from her research is that we've simply asked too much of pre-K, based on early results from what were essentially showcase pilot programs. "We tend to want a magic bullet," she says.

"Whoever thought that you could provide a 4-year-old from an impoverished family with 5 1/2 hours a day, nine months a year of preschool, and close the achievement gap, and send them to college at a higher rate?" she asks. "I mean, why? Why do we put so much pressure on our pre-K programs?"

We might actually get better results, she says, from simply letting little children play.

The Power of Hands-On Science Education

Research shows that hands-on learning is extremely effective for students of all ages, particularly when it comes to science education. Waldorf Education employs an experiential approach in all subjects, especially in science. Students learn through observation and experimentation, rather than just memorizing formulas. This engages the senses and encourages critical thinking and problem-solving, which fosters wonder, curiosity, and a deeper understanding of scientific phenomena.

Learning about science through listening to lectures and reading about it, though valuable, isn’t always enough to truly engage students. Learning by doing science through hands-on science activities and experiments lets students see what they’ve learned in action and develop a deeper understanding of the subject. Hands-on learning is just another way to refer to learning by doing. Allowing students to discover more about scientific concepts through hands-on science activities, experiments, and projects is a proven way to increase engagement and academic achievement.

A study done by the Canadian Center of Science and Education found that children can learn mathematics and sciences effectively even before being exposed to formal school curriculum if basic mathematics and science concepts are communicated to them early using activity-oriented (hands-on) methods of teaching. Mathematics and science are practical and activity oriented and can best be learned through inquiry (Okebukola in Mandor, 2002) and through intelligent manipulation of objects and symbols (Ekwueme, 2007). The study looked at the impact of a hands-on approach on students’ academic performance and the students’ opinion about this activity-based methodology and showed positive improvement in both the students’ performance and participation in mathematics and basic science activities and willingness on the part of the teachers to use hands-on approaches in communicating mathematical and scientific concepts to their students.

A study done by the Canadian Center of Science and Education found that children can learn mathematics and sciences effectively even before being exposed to formal school curriculum if basic mathematics and science concepts are communicated to them early using activity-oriented (hands-on) methods of teaching. Mathematics and science are practical and activity oriented and can best be learned through inquiry (Okebukola in Mandor, 2002) and through intelligent manipulation of objects and symbols (Ekwueme, 2007). The study looked at the impact of a hands-on approach on students’ academic performance and the students’ opinion about this activity-based methodology and showed positive improvement in both the students’ performance and participation in mathematics and basic science activities and willingness on the part of the teachers to use hands-on approaches in communicating mathematical and scientific concepts to their students.

What Is Hands-On Science?

Hands-on science can be defined as students getting their hands on materials, performing experiments, exploring phenomena, and trying out ideas. According to research, hands-on science usually involves “physical materials to give students first-hand experience in scientific methodologies” but can also include virtual labs. Labs, experiments, and projects are all potential hands-on science activities.

Why Hands-On Learning Is Important in Science

Hands-on learning is more than just a way to get students to experiment with science equipment or be immersed in a virtual world. Also, hands-on learning does more than bring fun to learning. This approach is proven to increase student engagement and understanding of scientific concepts.

Hands-on learning can also connect to inquiry-based learning in science, another teaching approach that’s proven to increase student engagement. Inquiry-based science instruction encourages students to ask questions they are interested in and investigate those questions. Hands-on science is one of many ways students can explore inquiries, whether the procedure is designed by the teacher or student. Let’s delve into the additional benefits of hands-on learning in science.

Benefits of Hands-On Learning in Science

Increases Retention: Active learning, such as through hands-on activities, has been proven to be effective at promoting retention. When students apply what they’ve learned in the classroom through hands-on science experiments and activities, students can better understand concepts.

- Improves Performance on Assessments: Research from the University of Chicago shows that hands-on science can improve student outcomes. Participating in the learning process through learning by doing helps students forge a deeper understanding of the scientific concepts taught in class.

- Provides a Sense of Accomplishment: Teachers have recognized that hands-on science provides students with a sense of accomplishment. At the end of a hands-on activity or experiment, students can see the immediate results of their learning. Learning new ideas can take a long time, but when the learning is hands-on, students reach a clear stopping point and can look back at what they did.

- Supports Students with Learning Barriers: Hands-on learning is a proven way to support students with learning barriers, such as multilingual learners and students with autism. Research has shown that students who are just beginning to learn English can benefit from visual resources and hands-on activities that help them understand new words and concepts in English. Additionally, research has shown that hands-on learning can enhance the learning process for students with autism.

- Develops Critical Thinking Skills: Overall, hands-on learning develops students’ critical thinking skills. Through doing hands-on activities and experiments, students have the chance to connect to and apply what they’ve learned in class to complete their projects.

Steiner School Waboba Experiment

Originally Published in the Waboba Journal

Earlier this year, Noelle Frerichs, a physics teacher at Rudolf Steiner High School in Ann Arbor, Michigan, reached out to us about wanting to get her hands on Waboba Pro Balls for an upcoming classroom experiment she was doing. The experiment would involve throwing balls up in the air to calculate the height of each throw using knowledge of the speed of free fall. At first we offered to send Moon Balls since they bounce super high, but Noelle advised it was best to stick with the Waboba Pro balls to get the desired results. (Moon Balls would hit the ceiling in the gym, which would make it problematic for the calculation. Naturally.)

You see, Noelle was planning a series of labs for her 10th grade physics (mechanics) class, where the students discover the acceleration of objects in free fall and learn to calculate the speed and height of a projectile. She thought of the gel Waboba balls because her dog has the pet version - the Waboba Fetch (she has 4, a true furbobian). Noelle knew her students would feel safer trying to catch soft Waboba balls over a hard softball, and others would feel safe with balls flying over their heads too. Plus, they could do the experiment in the gym if needed, and the Pro balls would be heavy enough to get good height, minimizing the effect of air resistance, which would skew their results.

You see, Noelle was planning a series of labs for her 10th grade physics (mechanics) class, where the students discover the acceleration of objects in free fall and learn to calculate the speed and height of a projectile. She thought of the gel Waboba balls because her dog has the pet version - the Waboba Fetch (she has 4, a true furbobian). Noelle knew her students would feel safer trying to catch soft Waboba balls over a hard softball, and others would feel safe with balls flying over their heads too. Plus, they could do the experiment in the gym if needed, and the Pro balls would be heavy enough to get good height, minimizing the effect of air resistance, which would skew their results.

After we sent Noelle some Waboba Pro Balls on the house (we love our teachers), she kept us posted about the experiment and answered some of our other questions too. We hope Noelle's story inspires other teachers to bring Waboba into the classroom to keep life and learning fun!

When/how did you first discover Waboba?

I first discovered Waboba in a small outdoor equipment store in Northport, MI. They sold the Waboba balls that you can bounce across the water and I bought one for my kids, then I later bought the set for dogs. My dog loves that ball, and it’s the only ball she will play with and chase! It’s also the way we get her in the water in the summertime.

How did your students respond to the experiment?

The students enjoyed throwing the Waboba balls as high as possible. They’re amazing because they’re soft but have a good weight to them, so they easily move through the air and can go very high. The students used timers to measure how long the balls were in the air in order to later calculate how high they could throw. Some students were throwing the balls over 50 feet into the air, but there were a few who were almost afraid to throw them and only tossed them about 7 feet high. They had to be encouraged to really throw them!

Any funny stories to share from the lesson?

Any funny stories to share from the lesson?

One of the students threw a ball so high that it went onto the roof of our gym. It’s still there because we don’t have a ladder high enough to get it down!

How is Steiner School different from other schools?

Something that sets Steiner (a Waldorf school) apart is that we work hard to meet students where they are developmentally. This means that in the preschool years the students’ time is primarily spent playing, to develop a healthy imagination, body and senses, as well as doing meaningful and fun work such as cooking and baking. They also hear many stories to foster the formation of mental pictures which later supports reading comprehension. In the lower grades the students transition from a more movement-based curriculum to learning about nature, cultures and sciences primarily through stories to which they connect deeply. The upper grades and high school are where the curriculum shift to more deeply intellectual topics and conversations around culture, literature and the sciences. Throughout our school the students are given a balanced curriculum including subjects lessons, arts, music and movement. Our student-centered approach also cultivates and establishes substantial relationships and helps develop social skills and moral character, as well as, offering a college-prep education.

How do you keep your students engaged in a tech-heavy world?

Something that sets Steiner apart is that we base our science lessons on experiences instead of textbooks or videos. In our science classes, students always start with hands-on experiences. Therefore, the sciences lessons begin in the laboratory and in the field. Observation and experimentation of the phenomena is the basis for the development of the laws and theories of modern science. The result is that we are educating the students to think and discover for themselves, which will serve them particularly well in the sciences but will also be beneficial no matter what their future career will be.

Favorite memory as a teacher:

I love seeing the growth of the students from 9th grade through 12th grade. Students come to us in 9th grade, some with many worries and insecurities and others with an overabundance of confidence. They are often very social but can be lacking in organizational skills, responsibility and social compassion. They grow and change so much from 9th to 12th grade and develop into caring and compassionate young adults.

Favorite memory as a student:

I loved chemistry and physics classes as a student. I remember the day my physics teacher did a demonstration where two balls were simultaneously released from the same height. One was launched horizontally and the other was dropped vertically. I was shocked that they hit the ground at the same time. I really thought the one that was launched horizontally would have taken longer to hit the ground. In retrospect, I would have had a hard time believing my teacher if he told us they would hit the ground at the same time without showing us that demonstration. Instead of focusing on questioning the truth of the statement that they would land at the same time, seeing the demonstration first engaged and interested me, and caused me to focus on questioning why they landed at the same time.

How do you Keep Life Fun with your students?

How do you Keep Life Fun with your students?

Because we start every topic with a demonstration or lab experience, the classes are naturally a lot of fun. The students enjoy hands-on learning. We also have engaging discussions in order to understand the phenomena that we investigate. The students enjoy sharing their thoughts and ideas, and it brings a social component to the lessons that would be absent if I was just lecturing. One day the students sat on scooters and raced through the gym to experience relative velocity. Another day I led them in an organized game of tug of war, an experience which led us to discuss vectors and the idea of equilibrium. There are so many examples of experiences the students have in the sciences, in chemistry, physics and the life sciences, throughout their four years in the high school. In their senior year the students travel to Maine as part of their Zoology lessons. We meet up with students from other Waldorf schools from across the country to study the coastal land and the abundance of life in the tide pools.

Did you have a favorite teacher when you were younger that inspired you to teach?

When I was in high school, I had no inclination to ever teach. I was very shy and wasn’t comfortable being in front of a room. My speech class in college was terrifying. I went to school to be an engineer and worked in the automotive industry for 13 years. Although I enjoyed my co-workers and many aspects of engineering work, I felt drawn to do something more meaningful. I’d had children by that point and had discovered the local Waldorf school. I was impressed by the curriculum and the way it built compassion, interest, imagination and logical thinking. Having spent 13 years in engineering, I could directly see the connections between the skills being built in the school and the skills needed for a successful career in engineering.

What inspired you to teach physics?

In order to truly understand a phenomenon, you have to understand it through your own experience. If someone were to give you a mathematical formula explaining motion, you might be able to understand the math, use it to calculate the position vs time, and even graph the motion. However, in order to truly make sense of the model you’d have to be able to connect it to your own experience. You’d have to be able to visualize the motion of the ball. It would be helpful to connect to your experience of throwing a ball straight up, or as far horizontally as you can. Through your own experience you already know and understand so much more than you realize. By connecting to that experience and then applying the math, you can understand the phenomena and the mathematical model that follows. Starting out of their own experience trains students to use their own experience to support their understanding. It also helps them to develop self-confidence as they realize the inherent knowledge they can tap into if they just take the time to recognize what they already fundamentally know to be true through their own experience. I wanted to teach physics in order to help students realize that they have the capacities to figure things out, and to give them experiences and practice doing so, in order to help them develop interest in the world and confidence in themselves.

Thanks to Noelle for taking the time to answer our questions and for sharing her story with us. We wish we were in her class!

Education for an Unpredictable Future

Teens Feel Ready for College, But Not So Much for Work

A new poll found that 74 percent of high school students think they’ll have a job in 20 years that hasn’t been invented yet. How do schools prepare students for that future? In Waldorf education we focus on helping students develop creativity and problem solving skills, communication, teamwork, and empathy, as well as the ability to take their ideas and put them into practice in the real world. These skills are foundational, and prepare students to successfully navigate the unpredictable and rapidly changing world of work and the diverse paths to higher education.

This piece was originally published by Alyson Klein in Education Week

High schoolers believe that their educational experience is getting them ready for college. But they’re less certain that their coursework is preparing them for the world of work.

That’s one of the big takeaways from surveys published recently by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, a nonprofit philanthropy based in Kansas City, Mo. The survey found that 81 percent of students felt that high school got them “very” or “somewhat” ready for college, compared with just 52 percent who felt it prepared them for the workforce.

“People are coming out of this sort of either-or,” said Aaron North, the vice president of education at the Kauffman Foundation. “You’re going to college, or you’re not. You’re getting a job after high school or you’re not. I think that’s not reflective of the reality of what’s on the other side of that graduation stage for them.”

He expects that, in the future, many students will transfer in and out of the workforce, gaining both educational credentials and on-the-job experience.

The survey also found that students and adults in general expect that technology and computer science jobs will be a major growth industry, with 85 percent of adults and 88 percent of students saying they expect those gigs to be in “much” or at least “somewhat more” in demand in the next decade.

And 74 percent of students think they’ll have a job in 20 years that hasn’t been invented yet.

Students “have only grown up in an age of really accelerated tech evolution,” North said. “I think that’s just the world that they are in. It is a world of creation. It is a world of change.”

‘Practical Connection’ Needed

Overwhelmingly, students, parents, and employers surveyed thought high schoolers would be better off learning how to file their taxes than learning about the Pythagorean theorem. At least 82 percent of parents, students, and employers thought schools should focus more on the 1040-EZ form than on that fundamental concept in geometry.

And 81 percent of students said they thought high school should focus most closely on helping students develop real-world skills such as problem-solving and collaboration rather than focusing so much on specific academic-subject-matter expertise.

“I think what that highlights is this idea that there needs to be this practical connection between what and how you are learning when you’re in school and what happens when you’re not in school,” North said. “So that doesn’t mean it has to be directly related to your everyday life, but it does mean that there could be a balance between things that may be applicable to a very narrow number of fields and things that are highly applicable to your life no matter what field you go into or what path you choose.”

Employers are also more likely to rate employees highly if they have completed an internship in their industry and have technical certifications than if they only have a college degree, the survey found.

But at the same time, 56 percent of employers surveyed felt that someone with only a high school degree would be held back from success in life because of their education. Students were even more convinced of the benefits of college, with 63 percent saying that having only a high school education would be a roadblock to success.

Still, most adults—59 percent of those surveyed—said they can’t connect what they learned in high school to their current jobs. That’s especially true of workers in blue-collar jobs, 61 percent of whom say that their jobs weren’t relevant to their high school educations, compared with 52 percent of white-collar employees.

“Parents who have experienced a noncollege pathway understand that those pathways are viable and they can lead to really good options,” North said. “A huge percentage of our population ends up not getting a college degree. And so there are millions and millions of people out there navigating the nondegree world, without much of a road map, the kind of road map we’ve provided around college. So I think that’s reflective of people who have found that and are understanding that, whether it’s for themselves or for their own kids.”

Old Strategies, New Jobs

Similarly, a separate report released last week by the RAND Corp., found that the needs of the workforce have transformed dramatically thanks to technological changes, globalization, and demographic shifts. But K-12 schools, postsecondary institutions, and job-training organizations are preparing students for jobs using essentially the same set of strategies they’ve been relying on for decades.

At the same time, employers are struggling to find workers with so-called “21st-century skills” such as information synthesis, creativity, problem-solving, communication, and teamwork. Yet the path forward is not easy for workers looking to upgrade their skills because of automation or shifting consumer demands.

“Employers are saying they can’t find employees with the skills they need, and on the other end, you have workers whose jobs have been made less relevant,” said Melanie Zaber, an associate economist at RAND, a nonprofit research organization.

The blame shouldn’t be all on schools, the RAND report emphasizes. Employers and education and job-training institutions don’t do a great job of systematically sharing information with schools that would allow them to better prepare students for the changing needs of the workforce. Plus, funding for K-12 education isn’t equally distributed and often neglects the areas that need strong pre-career training the most.

What also makes progress difficult is that high school principals rarely get to see how their students are doing years after they leave the classroom, Zaber said. “Letting high school principals see what happens when students leave their doors can help inform policy for where the gaps are, where the barriers are, where students are being let down,” she said.

If you are looking for the best game slots online in Southeast Asia, Rajawali888 or Rajawali888 it will be more interesting

For those curious about the Metaverse, don’t miss visiting our website

If you are looking for Zoho CRM Setup and Customization ,check out our website