Waldorf Graduates Pursue Meaningful Careers

Will My Child Succeed After Waldorf High School? The Research Says Yes

Choosing a high school is a critical decision, and parents often wonder: Will this education prepare my child for college, career, and life?

For families considering Waldorf high schools, this question is especially relevant. With experiential learning, seminar-style discussions, and an interdisciplinary curriculum, can Waldorf truly equip students for fields like medicine, law, technology, and business?

Decades of research say yes.

Waldorf Graduates Excel in Higher Education and Careers

A 60-year study (Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II, Mitchell & Gerwin, 2007) found that:

- 94% of Waldorf graduates attend college.

- 42% major in science-related fields—more than double the national average.

- Many earn advanced degrees in medicine, law, engineering, business, and the arts.

- Alumni thrive in fields ranging from finance and research to entrepreneurship and sustainability.

Waldorf Alumni Spotlight: Science in Action

After earning a degree in Earth Systems Engineering from the University of Michigan, Gavin Chensue ('06) joined the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps, leading critical climate studies worldwide.

"Steiner education gave me a taste of everything. When I needed direction in college, I remembered how much I loved studying weather and geology—and that led me to where I am today." - Gavin Chensue (RSSAA '06), Research Engineer at SRI International, Former NOAA Corps Officer

His story highlights how Waldorf graduates succeed in STEM, combining curiosity and real-world problem-solving to make a global impact.

Read the full studies:

- Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/research

- Into the World Study: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/graduate-outcomes

What Makes a Waldorf Education So Effective?

Contrary to the belief that test-driven education leads to success, research shows that employers and universities highly value graduates who:

✔ Think critically and independently

✔ Communicate clearly and persuasively

✔ Collaborate effectively

✔ Solve complex problems

✔ Adapt to a changing world

These are precisely the skills Waldorf high schools cultivate.

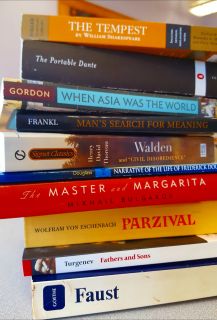

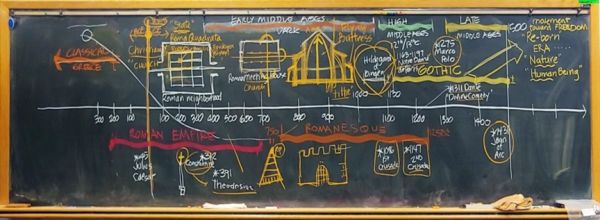

1. Depth Over Memorization: Lifelong Knowledge Retention

Rather than rote memorization, Waldorf fosters deep understanding:

- History is explored through primary sources and narratives.

- Science emphasizes hands-on experiments and independent research.

- Mathematics focuses on real-world application.

- Literature and philosophy encourage analytical discussions.

One employer noted:

“Waldorf students don’t just look for the right answer—they explore the why and how behind complex issues.”

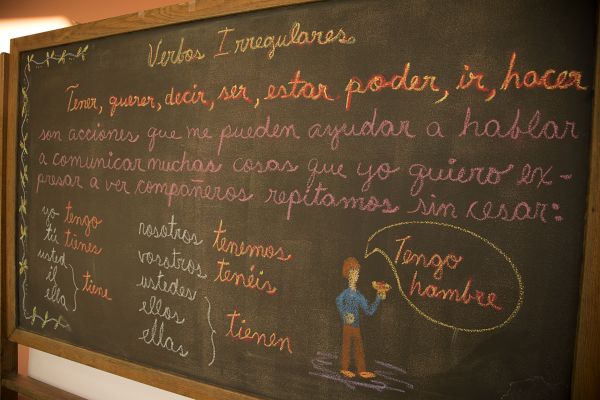

2. Seminar-Style Learning Develops Exceptional Communicators

Waldorf emphasizes oral presentations, debates, and collaborative discussions, preparing graduates for leadership roles in law, finance, business, and medicine.

Dr. Ilan Safit, co-author of *Into the World*, states:

“We consistently hear that Waldorf graduates excel at teamwork and leadership. Their ability to articulate complex ideas is a major asset.”

A study from Da Vinci Waldorf School found that Waldorf students select careers based on values and passion rather than prestige or income.

Final Thoughts: The Research Speaks for Itself

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Read more on Waldorf Graduates

Selecting a High School

Selecting a High School

Advice from Veteran Waldorf Educators

Choosing the right high school can feel like one of the most significant decisions a family will make in their child’s educational journey.

To bring clarity to this decision, we turned to two of our most experienced educators at the Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor: Margot Amrine, a longtime Waldorf teacher with over four decades of experience, and Dr. Siân Owen-Cruise, our former School Administrator, who has guided countless families through the high school selection process.

Today’s parents listen to and respect their children’s perspectives more than ever before- a positive shift in family dynamics. But as Margot reminds us, that doesn’t mean parents should surrender their leadership on big decisions.

“In our family we said that Waldorf Education for 9th and 10th grade was essential. At 11th grade, a different kind of maturity sets in; if our children had made compelling reasons to leave then, we would have considered. We never had these discussions!”

Dr. Owen-Cruise expands on this, acknowledging that social pressures play an outside role in an 8th Grader's thinking:

“It's natural for teenagers to focus on their peers and social dynamics when thinking about high school. As parents, we listen, we understand, and we take their feelings seriously- but ultimately, we need to lead this decision with wisdom and foresight.”

Dr. Owen-Cruise often frames the conversation with the rising student in the following way:

“Your parents will choose where you receive your high school education, with your input. YOU will choose where you go to college, with our parental input.”

Many families who have walked this path find that their children- whether they started in Waldorf Education or joined from another school-ultimately express gratitude that their parents guided this decision with their long-term development in mind.

Here are some other helpful tips and information when thinking about our own High School:

Waldorf Graduates Pursue Meaningful Careers

“Will My Child Succeed After Waldorf High School? The Research Says Yes” - Blog Article

Parents often ask: Does a Waldorf education prepare students for college, careers, and beyond? The answer is a resounding yes. Studies show that Waldorf graduates not only attend college at high rates but also excel in fields like science, medicine, law, and technology. Employers and universities consistently praise their ability to think critically, communicate effectively, and adapt to a changing world. Want to know why? This article dives into the research and real-world successes of our alumni.

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

"The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens" - Blog Article

In an age where screens dominate every aspect of life, imagine a school where students engage in real conversations, dive into hands-on projects, and focus fully in class—without the pull of notifications. Our phone-free policy isn’t just a rule; it’s a game-changer. See how it shapes our students’ social and academic lives!

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

Imagine a typical school day where students, between classes and during breaks, are glued to their smartphones—scrolling through social media, playing games, or texting. Conversations are sparse, eye contact is minimal, and the vibrant energy of youthful interaction seems subdued. Now, contrast this with a school environment where smartphones are set aside: students engage in lively face-to-face discussions, participate in spontaneous games, and immerse themselves fully in classroom activities without the constant pull of notifications. This is the reality we’ve cultivated at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, embracing a phone-free policy that fosters genuine connections and holistic development.

The Deeper Engagement of Phone-Free Education

At our school, we’ve observed that removing smartphones from the school day does more than just eliminate distractions—it rekindles a deeper, more meaningful engagement among students. Freed from screens, students rediscover the joy of direct communication, collaborative problem-solving, and hands-on learning. This environment aligns seamlessly with the principles of Waldorf education, emphasizing experiential learning and nurturing the whole child.

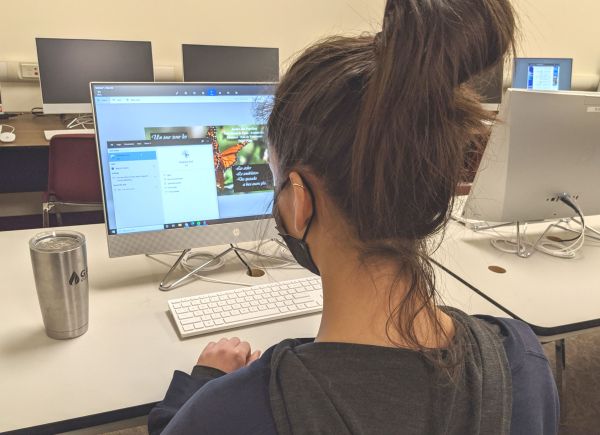

We Are Phone-Free, Not Tech-Free

While our school maintains a phone-free environment during school hours, we are not devoid of technology. In fact, our curriculum incorporates technology in age-appropriate ways to ensure students are prepared for the digital world:

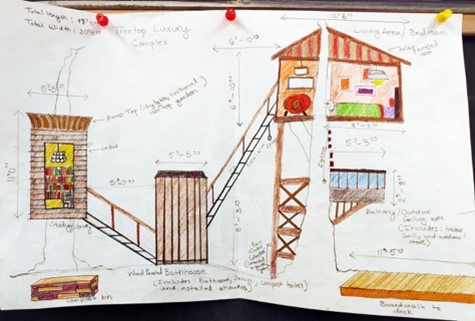

• Middle School: Students are introduced to computers and the internet in an intentional way that supports learning. Additionally, our middle school robotics club fosters interest in technology and engineering through hands-on projects. https://www.steinerschool.org/programs/extracurricular-activities.cfm

• High School: Our state-of-the-art computer lab facilitates courses in coding, digital literacy, and other computer science subjects. We also have an active high school robotics club where students collaborate on competitive projects that develop real-world problem-solving skills. https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-education.cfm

Many of our graduates go on to thrive in technology fields, excelling in computer science, engineering, and data analysis. Research shows that Waldorf graduates develop strong interdisciplinary thinking skills that prepare them for success in fields that require both creativity and technical expertise.

Leading the Way in Ann Arbor

Our commitment to a phone-free school day positions us as pioneers in the Ann Arbor educational community. While some other local schools have implemented partial restrictions, our comprehensive approach ensures that students remain unplugged throughout the day—including breaks and transitions between classes.

Several Ann Arbor schools are recognizing the value of limiting phone use:

• Forsythe Middle School and Tappan Middle School both require students to keep phones in lockers during school hours. https://forsythe.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy, https://tappan.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy

• Huron High School has introduced classroom phone storage policies in its Mathematics and English departments to help students stay focused. https://thehuronemery.com/9731/news/cell-phone-use-teacher-led-procedures-to-enrich-student-experience/

The Transformative Power of Disconnecting

The shift to a phone-free environment has yielded profound benefits:

• Enhanced Academic Focus: Without the allure of smartphones, students engage more deeply in lessons, leading to improved comprehension and retention.

• Strengthened Social Bonds: Face-to-face interactions during breaks and collaborative projects foster authentic relationships and empathy among students.

• Improved Mental Well-being: Reducing screen time has been linked to decreased anxiety and stress, allowing students to be more present and mindful.

Embracing a Connected Future Without Phones

As more schools recognize the value of limiting smartphone use, it’s evident that this movement is not about restricting technology but about reclaiming the essence of human connection and focused learning. By leading the way in this initiative, Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor not only adheres to the foundational principles of Waldorf education but also prepares students for careers in STEM, the arts, and beyond.

We invite families seeking a nurturing, distraction-free educational environment to join us in this journey, where students can truly engage with the world around them and develop into well-rounded individuals.

Explore the experiences of other schools with phone-free policies:

• “New data reveals shocking trend since school mobile phone ban”

- “The big smartphone school experiment”

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/inside-schools-ban-smartphones-6knb8qtfc

- “Cell phones hinder classroom learning. Texas should tell school districts to lock them up”

- "Waldorf Schools are Media Literacy Role Models"

https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-schools-are-media-literacy-role-models/

Pushing Academics into Preschool Can Be Harmful

A comprehensive study finds significant drawbacks to pushing academics as early as in preschool. Researchers found that any initial academic gains were quickly erased, and children who attended academic-focused Pre-K were actually behind their peers in elementary and middle school. Another troubling finding was that students who experienced early academic pressure showed dramatic increases in behavioral issues later on. In Waldorf education, we focus on what is developmentally appropriate for each age group, understanding that preschool-age children especially need play, movement, and art, which are all critical to social-emotional health and future academic success.

This article was originally published by Anya Kamenetz on NPR.org

A top researcher says it's time to rethink our entire approach to preschool

Dale Farran has been studying early childhood education for half a century. Yet her most recent scientific publication has made her question everything she thought she knew.

"It really has required a lot of soul-searching, a lot of reading of the literature to try to think of what were plausible reasons that might account for this."

And by "this," she means the outcome of a study that lasted more than a decade. It included 2,990 low-income children in Tennessee who applied to free, public prekindergarten programs. Some were admitted by lottery, and the others were rejected, creating the closest thing you can get in the real world to a randomized, controlled trial — the gold standard in showing causality in science.

Farran and her co-authors at Vanderbilt University followed both groups of children all the way through sixth grade. At the end of their first year, the kids who went to pre-K scored higher on school readiness — as expected.

But after third grade, they were doing worse than the control group. And at the end of sixth grade, they were doing even worse. They had lower test scores, were more likely to be in special education, and were more likely to get into trouble in school, including serious trouble like suspensions.

"Whereas in third grade we saw negative effects on one of the three state achievement tests, in sixth grade we saw it on all three — math, science and reading," says Farran. "In third grade, where we had seen effects on one type of suspension, which is minor violations, by sixth grade we're seeing it on both types of suspensions, both major and minor."

That's right. A statewide public pre-K program, taught by licensed teachers, housed in public schools, had a measurable and statistically significant negative effect on the children in this study.

Farran hadn't expected it. She didn't like it. But her study design was unusually strong, so she couldn't easily explain it away.

"This is still the only randomized controlled trial of a statewide pre-K, and I know that people get upset about this and don't want it to be true."

Why it's a bad time for bad news

It's a bad time for early childhood advocates to get bad news about public pre-K. Federally funded universal prekindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds has been a cornerstone of President Biden's social agenda, and there are talks about resurrecting it from the stalled-out "Build Back Better" plan. Preschool has been expanding in recent years and is currently publicly funded to some extent in 46 states. About 7 in 10 4-year-olds now attend some kind of academic program.

This enthusiasm has rested in part on research going back to the 1970s. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman, among others, showed substantial long-term returns on investment for specially designed and carefully implemented programs.

To put it crudely, policymakers and experts have touted for decades now that if you give a 4-year-old who is growing up in poverty a good dose of story time and block play, they'll be more likely to grow up to become a high-earning, productive citizen.

What went wrong in Tennessee

No study is the last word. The research on pre-K continues to be mixed. In May 2021, a working paper (not yet peer reviewed) came out that looked at Boston's pre-K program. The study was a similar size to Farran's, used a similar quasi-experimental design based on random assignment, and also followed up with students for years. This study found that the preschool kids had better disciplinary records and were much more likely to graduate from high school, take the SATs and go to college, though their test scores didn't show a difference.

Farran believes that, with a citywide program, there's more opportunity for quality control than in her statewide study. Boston's program spent more per student, and it also was mixed-income, whereas Tennessee's program is for low-income kids only.

So what went wrong in Tennessee? Farran has some ideas — and they challenge almost everything about how we do school. How teachers are prepared, how programs are funded and where they are located. Even something as simple as where the bathrooms are.

In short, Farran is rethinking her own preconceptions, which are an entire field's preconceptions, about what constitutes quality pre-K.

Do kids in poverty deserve the same teaching as rich kids?

"One of the biases that I hadn't examined in myself is the idea that poor children need a different sort of preparation from children of higher-income families."

She's talking about drilling kids on basic skills. Worksheets for tracing letters and numbers. A teacher giving 10-minute lectures to a whole class of 25 kids who are expected to sit on their hands and listen, only five of whom may be paying any attention.

"Higher-income families are not choosing this kind of preparation," she explains. "And why would we assume that we need to train children of lower-income families earlier?"

Farran points out that families of means tend to choose play-based preschool programs with art, movement, music and nature. Children are asked open-ended questions, and they are listened to.

This is not what Farran is seeing in classrooms full of kids in poverty, where "teachers talk a lot, but they seldom listen to children." She thinks that part of the problem is that teachers in many states are certified for teaching students in prekindergarten through grade 5, or sometimes even pre-K-8. Very little of their training focuses on the youngest learners.

So another major bias that she's challenging is the idea that teacher certification equals quality. "There have been three very large studies, the latest one in 2018, which are not showing any relationship between quality and licensure."

Putting a bubble in your mouth

In 2016, Farran published a study based on her observations of publicly funded Tennessee pre-K classrooms similar to those included in this paper. She found then that the largest chunk of the day was spent in transition time. This means simply moving kids around the building.

Partly this is an architectural problem. Private preschools, even home-based day cares, tend to be laid out with little bodies in mind. There are bathrooms just off the classrooms. Children eat in, or very near, the classroom, too. And there is outdoor play space nearby with equipment suitable for short people.

Putting these same programs in public schools can make the whole day more inconvenient.

"So if you're in an older elementary school, the bathroom is going to be down the hall. You've got to take your children out, line them up and then they wait," Farran says. "And then, if you have to use the cafeteria, it's the same thing. You have to walk through the halls, you know: 'Don't touch your neighbor, don't touch the wall, put a bubble in your mouth because you have to be quiet.' "

One of Farran's most intriguing conjectures is that this need for control could explain the extra discipline problems seen later on in her most recent study.

"I think children are not learning internal control. And if anything, they're learning sort of an almost allergic reaction to the amount of external control that they're having, that they're having to experience in school."

In other words, regularly reprimanding kids for doing normal kid stuff at 4 years old, even suspending them, could backfire down the road as children experience school as a place of unreasonable expectations.

We know from other research that the control of children's bodies at school can have disparate racial impact. Other studies have suggested that Black children are disciplined more often in preschool, as they are in later grades. Farran's study, where 70% of the kids were white, found interactions between race, gender, and discipline problems, but no extra effect of attending preschool was detected.

Where to go from here

The United States has a child care crisis that COVID-19 both intensified and highlighted. Progressive policymakers and advocates have tried for years to expand public support for child care by "pushing it down" from the existing public school system, using the teachers and the buildings.

Farran praises the direction that New York City, for one, has taken instead: a "mixed-delivery" program with slots for 3- and 4-year-olds. Some kids attend free public preschool in existing nonprofit day care centers, some in Head Start programs and some in traditional schools.

But the biggest lesson Farran has drawn from her research is that we've simply asked too much of pre-K, based on early results from what were essentially showcase pilot programs. "We tend to want a magic bullet," she says.

"Whoever thought that you could provide a 4-year-old from an impoverished family with 5 1/2 hours a day, nine months a year of preschool, and close the achievement gap, and send them to college at a higher rate?" she asks. "I mean, why? Why do we put so much pressure on our pre-K programs?"

We might actually get better results, she says, from simply letting little children play.

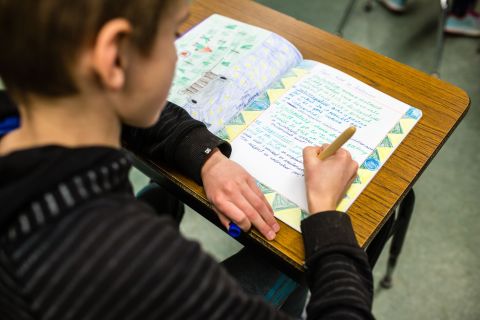

The Waldorf Approach to Reading

Could pushing kids to read too early be counterproductive? Studies have shown that academic demands on young children have increased significantly in the last few decades, with mixed results. Many children feel unnecessary stress in response to early academic pressure, with long-term negative effects. In the Waldorf approach, children build their foundation to reading and writing organically, learning letters and sounds through stories, songs, word games, and more. This low-stress, natural approach starts in preschool and is integrated into every subject, every day. Our story-first approach helps children feel excited, rather than pressured, to learn to read and write, and engages their natural curiosity and love of learning.

This article was originally published by Whitney Ballard on the Bored Teachers website.

Study Shows: Pushing Kids to Read Too Much, Too Early is Counterproductive

It’s no secret that there is a constant push to do MORE and be BETTER in education. It often feels like a never-ending competition. If your child performs well, you “should” push him or her to be better than their peers. Your school may perform well, but you “should” push for the best in the state. Your state may do well, but you “should” push to beat other regions. In terms of news, our country is “so far behind”. These not-so-subtle messages are pushing our students, teachers, and all other school personnel far beyond age-appropriate performance levels. It starts with reading. Exactly why are we pushing kids to read so early?

In fact, learning to read too early can actually be counterproductive. Studies show it can lead to a variety of problems including increased frustration, misdiagnosed disorders, and unnecessary time and money spent teaching kids skills they don’t even have the skillset to understand yet.

“Escalating Academic Demand in Kindergarten: Counterproductive Policies” is one study that exemplifies the reverse of pushing children to read before they are ready:

“Narrow emphasis on isolated reading and numeracy skills is detrimental even to the children who succeed and is especially harmful to children labeled as failures…academic demands in kindergarten and first grade are considerably higher today than 20 years ago and continue to escalate.”

While it may seem like our kids are being pushed to succeed, they are often pushed too hard. They eventually accept defeat because it becomes increasingly difficult for students to keep up with impossible standards. Once kids “fall behind” according to educational standards, it creates an “I’m not good enough” mentality. This often sticks with them through school. The early years are extremely important for building confidence and a positive attitude. Yet every year, we fill the early years with more requirements that are proven to be confidence-killers and negative reinforcements.

There are virtually zero studies that show proof that reading early actually helps kids succeed long-term.

From a secondary teacher’s perspective, I have never been able to tell which child learned to read first, or which child could recite their ABCs before they were 3 years old. I could, however, tell which students felt confident in his or her abilities. Likewise, I could tell which students struggled to believe in themselves and which students expected to fail. As a teacher, I worry that we are putting skills like reading above social skills and confidence-building.

I could, however, tell which students felt confident in his or her abilities. Likewise, I could tell which students struggled to believe in themselves and which students expected to fail. As a teacher, I worry that we are putting skills like reading above social skills and confidence-building.

The teacher part of me can see the long-term struggle, but the parent-of-young-kids part of me can see the current stress. It is extremely difficult not to buy into the hype—the kind that tells you your young children need every educational toy on the market. Society tells mamas (and daddies) that their children are falling behind in sneaky ways through the use of advertisements, social media, etc.

Parents are constantly seeing children praised for their outstanding achievements and are being asked to compare their own children with the ‘exception’, not the rule. Many kids WANT to accelerate the process and constantly learn MORE. That is perfectly fine. Many kids also want to take their sweet time. That is also perfectly fine.

No two kids are the same. And no two students are the same. No kid should be pushed too hard too early to do anything, including reading.

As a teacher, I am constantly reassuring parents that their children are on track, despite the constant “push” for more. And as a parent, I am constantly re-centering myself on the idea that our children are natural learners who learn more from the world around them at a young age. As a friend, I want to encourage you to research the lack of benefits of learning to read too early—and look to your child for cues on when he or she is actually ready.

What age is truly the right age to learn to read? It depends on the individual.

In the meantime, let’s focus on building confidence, fostering creativity, and allowing our young kids to learn in the ways that suit them best.

The Value of an Unhurried Childhood

A recent New York Times article highlighted the importance of giving children an unhurried childhood, without an overpacked schedule of extracurricular activities and excessive homework. The pressure on Gen Z to excel at a young age has led to decreased mental health and increasing struggles at school. Waldorf Education takes a balanced approach, with plenty of time for children to play and explore, while also providing a joyful and well-rounded education that instills essential life skills, sparks a lifelong love of learning, and prepares them for a successful future.

This article was written by Shalini Shankar and originally published on July 9, 2021 in the New York Times

A Packed Schedule Doesn’t Really ‘Enrich’ Your Child

When the extracurricular-industrial complex came to a grinding halt last spring, parents were left scrambling to fill vast hours of unscheduled time. Some activities moved to remote instruction but most were canceled, and keeping children engaged became the bane of parents’ existence. Understandably, screens became default child care for younger kids and social lifelines for older ones.

As American society reopens, going back to our children’s prepandemic activities looks like an enticing way to reintroduce upper-elementary through high-school-age kids to the outside world. For parents with economic means, it’s tempting to return to a full slate of language classes, sports, music lessons and other extracurriculars — a guilt-free plan to keep kids busy with “enriching” activities while we get our jobs done.

But I suggest pausing before filling up their calendars again. We should not simply return children to their hectic prepandemic schedules.

Certainly, some amount of extracurricular activity can offer a welcome break from screens and help children nurture interests. But for Generation Z, the over-scheduling of extracurricular activities has been bad for stress and mental health and even worse for widening racial gaps. Moreover, as I learned when I conducted anthropological research for my book “Beeline: What Spelling Bees Reveal About Generation Z’s New Path to Success,” it no longer consistently improves the prospects of the white middle-class kids for whom it was designed.

But what can parents do with our kids instead? The answer is simple, though not easy to carry out: We can teach them (and perhaps relearn ourselves) the value of unstructured time and greater civic participation.

But what can parents do with our kids instead? The answer is simple, though not easy to carry out: We can teach them (and perhaps relearn ourselves) the value of unstructured time and greater civic participation.

This does not mean we should quit our day jobs and devote ourselves instead to endless hours of building forts and playing games. Exposing children to sports, music, art, programming or dance certainly has benefits — including physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and fun — but there are also good reasons to give children time to be bored. Not least of these is it forces them to figure out a way to entertain themselves.

For many kids today, scheduled time and down time on their screens are the only states of being. Paradoxically, scheduled unstructured time could address this. Cooking, reading a book, art projects and neighborhood walks are unlikely to completely replace screens, but routinizing blocks of time for these self-sustaining activities each day or several times a week could introduce children and teenagers to new pleasures, and at the very least invite calmness.

Gen Z acutely feels the pressure to be accomplished at a younger age. As kids take on a wider range of challenging activities younger, a trend that began with millennials but has grown to steroidal levels, the criteria for standing out in the college admissions process have shot up accordingly. It’s no wonder kids are stressed out.

The Slacker Generation, an initially disparaging label that Gen Xers have reclaimed, did not have to build a childhood résumé brimming with skills, expertise and accolades to get into college. Now many of these former slackers are parents worried about whether their kids are doing enough to stay competitive in college admissions and the job market. Those who can afford it feel pressure to pad their kids’ résumés as much as they can. A 2019 survey found that more than a quarter of “sports parents” spent upward of $500 per month, with some spending over $1,000 and jeopardizing their retirement savings.

But it’s clear by now that all this expensive enrichment won’t ensure kids’ success. Despite middle- and upper-class millennials mortgaging their childhood to get into college and then toiling through early adulthood in unpaid internships, they are unable to acquire the levels of economic and social security still held by their baby boomer parents.

Perhaps that’s why Gen Z has shown astute awareness of the dangers of overwork, with some high-profile Zoomers demonstrating acts of radical self-preservation. The Gen Z tennis star Naomi Osaka, for example, recently chose to prioritize her well-being over her career’s demands when she dropped out of the French Open after officials fined her for declining to participate in its post-match news conferences. Gen Z seems to have accepted that no matter how much you love your job, your job won’t love you back. Their parents — Gen Xers and even older millennials — were late to this lesson, and if they learned it at all, it was often only when they hit a wall with burnout.

Of course, preparing children for college and the job market is not the only goal of parents shelling out for guitar lessons or robot-making labs. Parents are also eager to expose their children to different ways of using their minds and bodies in the hope that they’ll discover passions that could become vocations, or simply lifelong joys. One passion that’s worth trying to instill is civic participation.

Of course, preparing children for college and the job market is not the only goal of parents shelling out for guitar lessons or robot-making labs. Parents are also eager to expose their children to different ways of using their minds and bodies in the hope that they’ll discover passions that could become vocations, or simply lifelong joys. One passion that’s worth trying to instill is civic participation.

As parents, we can reinforce the importance of caring beyond one’s own success. Taking your kids to volunteer or to protest injustices they see in the world are good ways to show them what it looks like to give back and replenish. The human and nonhuman connections they will make at food pantries and animal shelters can help kids cultivate empathy — itself a valuable skill for navigating life — while offsetting the anxiety footprint caused by today’s inflated standards for success.

It might feel counterintuitive to deny your children the leg up in life that many extracurriculars promise, but it’s worth examining that impulse too. The pandemic has exacerbated existing socioeconomic disparities, especially along racial lines. With widening wealth gaps, there will be even fewer opportunities to prioritize extracurricular activities for low-income kids. Rethinking the value of a packed calendar offers a concrete opportunity to narrow the racial and economic gaps between privileged and underprivileged kids.

Replacing video games with nature walks might not make you the most popular parent. Your kids may complain a little (or a lot) about losing some of their organized fun, since boredom is a feeling they’ve rarely experienced. But they’ll figure it out.

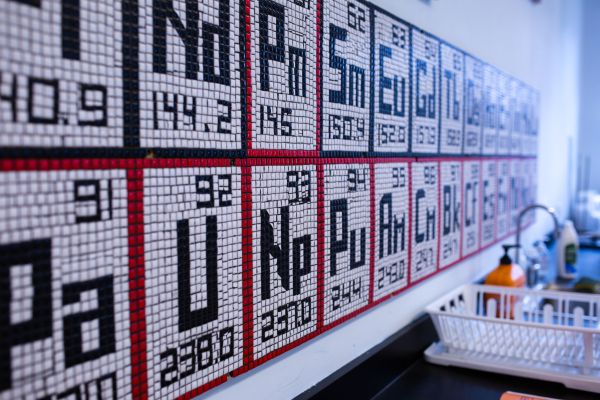

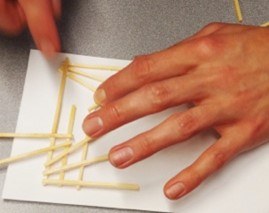

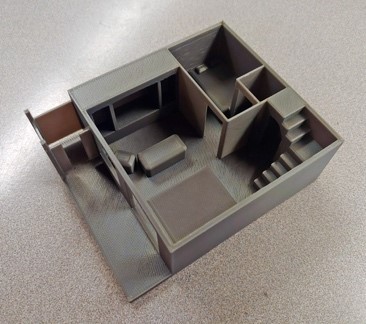

The Power of Hands-On Science Education

Research shows that hands-on learning is extremely effective for students of all ages, particularly when it comes to science education. Waldorf Education employs an experiential approach in all subjects, especially in science. Students learn through observation and experimentation, rather than just memorizing formulas. This engages the senses and encourages critical thinking and problem-solving, which fosters wonder, curiosity, and a deeper understanding of scientific phenomena.

Learning about science through listening to lectures and reading about it, though valuable, isn’t always enough to truly engage students. Learning by doing science through hands-on science activities and experiments lets students see what they’ve learned in action and develop a deeper understanding of the subject. Hands-on learning is just another way to refer to learning by doing. Allowing students to discover more about scientific concepts through hands-on science activities, experiments, and projects is a proven way to increase engagement and academic achievement.

A study done by the Canadian Center of Science and Education found that children can learn mathematics and sciences effectively even before being exposed to formal school curriculum if basic mathematics and science concepts are communicated to them early using activity-oriented (hands-on) methods of teaching. Mathematics and science are practical and activity oriented and can best be learned through inquiry (Okebukola in Mandor, 2002) and through intelligent manipulation of objects and symbols (Ekwueme, 2007). The study looked at the impact of a hands-on approach on students’ academic performance and the students’ opinion about this activity-based methodology and showed positive improvement in both the students’ performance and participation in mathematics and basic science activities and willingness on the part of the teachers to use hands-on approaches in communicating mathematical and scientific concepts to their students.

A study done by the Canadian Center of Science and Education found that children can learn mathematics and sciences effectively even before being exposed to formal school curriculum if basic mathematics and science concepts are communicated to them early using activity-oriented (hands-on) methods of teaching. Mathematics and science are practical and activity oriented and can best be learned through inquiry (Okebukola in Mandor, 2002) and through intelligent manipulation of objects and symbols (Ekwueme, 2007). The study looked at the impact of a hands-on approach on students’ academic performance and the students’ opinion about this activity-based methodology and showed positive improvement in both the students’ performance and participation in mathematics and basic science activities and willingness on the part of the teachers to use hands-on approaches in communicating mathematical and scientific concepts to their students.

What Is Hands-On Science?

Hands-on science can be defined as students getting their hands on materials, performing experiments, exploring phenomena, and trying out ideas. According to research, hands-on science usually involves “physical materials to give students first-hand experience in scientific methodologies” but can also include virtual labs. Labs, experiments, and projects are all potential hands-on science activities.

Why Hands-On Learning Is Important in Science

Hands-on learning is more than just a way to get students to experiment with science equipment or be immersed in a virtual world. Also, hands-on learning does more than bring fun to learning. This approach is proven to increase student engagement and understanding of scientific concepts.

Hands-on learning can also connect to inquiry-based learning in science, another teaching approach that’s proven to increase student engagement. Inquiry-based science instruction encourages students to ask questions they are interested in and investigate those questions. Hands-on science is one of many ways students can explore inquiries, whether the procedure is designed by the teacher or student. Let’s delve into the additional benefits of hands-on learning in science.

Benefits of Hands-On Learning in Science

Increases Retention: Active learning, such as through hands-on activities, has been proven to be effective at promoting retention. When students apply what they’ve learned in the classroom through hands-on science experiments and activities, students can better understand concepts.

- Improves Performance on Assessments: Research from the University of Chicago shows that hands-on science can improve student outcomes. Participating in the learning process through learning by doing helps students forge a deeper understanding of the scientific concepts taught in class.

- Provides a Sense of Accomplishment: Teachers have recognized that hands-on science provides students with a sense of accomplishment. At the end of a hands-on activity or experiment, students can see the immediate results of their learning. Learning new ideas can take a long time, but when the learning is hands-on, students reach a clear stopping point and can look back at what they did.

- Supports Students with Learning Barriers: Hands-on learning is a proven way to support students with learning barriers, such as multilingual learners and students with autism. Research has shown that students who are just beginning to learn English can benefit from visual resources and hands-on activities that help them understand new words and concepts in English. Additionally, research has shown that hands-on learning can enhance the learning process for students with autism.

- Develops Critical Thinking Skills: Overall, hands-on learning develops students’ critical thinking skills. Through doing hands-on activities and experiments, students have the chance to connect to and apply what they’ve learned in class to complete their projects.

Harvard Supports: Education Should Be Joyful

Research from Harvard Graduate School of Education emphasizes the importance of making education joyful. Compared with high-pressure, high-stakes, testing-driven environments, students retain more and process better in happy, lower-stress environments. In Waldorf Education, our intentional approach prioritizes engaged, enthusiastic learning and our teachers bring joy to every lesson, instilling a deep understanding of each subject and a lifelong love of learning.

This is an excerpt. The full article was originally published by Lory Hough in the Harvard Ed. Magazine https://www.gse.harvard.edu/ideas/ed-magazine/22/05/space-joy

Is learning even meant to be joyful?

Anyone who has picked up an instrument or tried to learn a new language knows that learning can be hard and frustrating. As Irby pointed out, “Learning is not always a joyous undertaking. Pushing through a difficult subject, topic, or painstaking assignment can be tough.”

But, he adds, “joy at school and in learning is a foundation from which students gain the confidence that academic struggle is temporary and worthwhile.” There’s also a very real connection to the brain. “The brain does not exist by itself,” writes Professor Jack Shonkoff, director of the Center on the Developing Child. “Connecting the brain to the rest of the body is critically important. When we’re stressed, every cell in the body is working overtime.”

But, he adds, “joy at school and in learning is a foundation from which students gain the confidence that academic struggle is temporary and worthwhile.” There’s also a very real connection to the brain. “The brain does not exist by itself,” writes Professor Jack Shonkoff, director of the Center on the Developing Child. “Connecting the brain to the rest of the body is critically important. When we’re stressed, every cell in the body is working overtime.”

Students who appear joyless or unmotivated may not be making voluntary choices, says Judy Willis, a neurologist who went on to teach middle school for 10 years. Their brains, as Shonkoff points out, may just be responding to what’s going on around them, like the ups and downs of the pandemic and our push to “catch up” academically in schools.

“The truth is that when we scrub joy and comfort from the classroom, we distance our students from effective information processing and long-term memory storage,” Willis recently wrote in the Neuroscience of Joyful Education. “Instead of taking pleasure from learning, students become bored, anxious, and anything but engaged. They ultimately learn to feel bad about school and lose the joy they once felt.” Neuroimaging studies and measurement of brain chemical transmitters reveal that “when students are engaged and motivated and feel minimal stress, information flows freely through the affective filter in the amygdala and they achieve higher levels of cognition, make connections, and experience ‘aha’ moments. Such learning comes not from quiet classrooms and directed lectures, but from classrooms with an atmosphere of exuberant discovery.”

Irby saw this with his own children. When school went remote, they were not happy. “On the best days, they were ambivalent. On the bad days, they were miserable,” he says. When they returned to in-person learning this past fall, things mostly got better. His son, a first-grader, didn’t like people being too close and didn’t want to be overly corrected for his efforts, but “they were very happy to return to school. They loved almost everything about returning, from packing their book bags, seeing their friends and socializing, to developing relationships with their teachers.”

Happy is great, but what about the important idea that we need to regain academic ground lost during the pandemic? As Professor Tom Kane and his colleagues at the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (CEPR) reveal in their new Road to COVID Recovery project, using real-time data and working with school districts across the country, learning loss from the pandemic is significant.

“I don’t think there’s a broad appreciation for the magnitude of the declines we’ve seen,” Kane told Ed. — the equivalent of kids missing three or four months of school last year. As he said in a recent The 74 article, “School districts have never had so many students so far behind.” And especially for some students. The Brookings Institute reported in March that test-score gaps between students in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by approximately 20% in math and 15% in reading, primarily during the 2020–21 school year.

CEPR has called for tutoring, extra periods of instruction, Saturday academies, and afterschool programs. Schools, they say, should focus for the next couple of years on getting students back to pre-COVID academic levels.

But what does catch up mean for the joy that tired students and teachers also desperately need?

In a Harvard EdCast interview in February (2022), Susan Engel, a senior lecturer at Williams College and author of the new book, The Intellectual Lives of Children, said, “I heard a first-grade teacher say to me, back in August, when she was planning her remote teaching, she said, ‘The parents are so worried that their children aren’t going to keep up this year.’ And I said, ‘Keep up with what?’ And she looked surprised, and she said, ‘Well, with the standards.’ But I mean, the standards are completely arbitrary. Who made up those standards? Just a lot of people sitting in rooms. I don’t know. And I’m not sure they were good standards in the first place, but it’s silly to let those constrain you too much as a teacher right now.”

Which is why it was interesting, says Wade Whitehead, a fifth-grade teacher in Virginia now in his 28th year of teaching, that in the spring of 2020, when it became clear that we weren’t going back to in-person any time soon, “the first two things we threw out the window were grades and standardized testing.”

Why was that, he wondered? “I think it’s because those two rob students and teachers of joy. I think it was to keep students and teachers happy” as we shifted focus to everyone’s crushing social-emotional (SEL) needs. And there were other changes that at any other time would have seemed radical: Schools shortened the school day and cut back to just a few class blocks a day. “COVID was an opportunity for schools to go deep. People had the freedom to just learn. If you want to be around someone who is happy, be around someone who’s just learning something to learn, especially face-to-face. You’re just happier that way.”

Unfortunately, says Whitehead, a Certificate in School Management and Leadership graduate, a year later, we “picked up those two apples” — grades and standardized tests — “and put them back in the cart. I’m not against grades or tests. I’m for amazing grading systems and amazing assessment and accountability systems.”

Durney agrees that the “normal” way of schooling wasn’t working for everyone and says that we can still rethink schooling.

“We need to use the pandemic as an opportunity to consider how we meet the needs of all our students through engaging tasks,” he says. “Students have access to apps, games, etc., and there are things that can and should be leveraged when designing learning opportunities. It isn’t just academics that students missed over the past two years. They need opportunities to engage in activities that allow them to build and strengthen their SEL skills. Rigor can and should be fun!”

Kane agrees and says that academics and emotional care go hand-in-hand. If students feel more comfortable being back in school, they are going to have an easier time focusing, just as finding success in the classroom can lead to positive effects on mental health.

Irby also says it’s not an either-or as we move forward.

“I would say to educators who want to prioritize getting kids up to speed academically over joy that the two are not mutually exclusive. They should think about them as mutually reinforcing,” he says. “Not only do joy and academic rigor go hand in hand, but tactful educators plan to ensure both happen in tandem.” He noted that Gholdy Muhammad’s framework outlined in her book Cultivating Genius includes five pillars to consider when planning lessons, and joy is one of them. “An example is children’s museums, which offer learning opportunities that center play and fun. Exhibit curators plan with joy and excitement at the center of their learning design, but they don’t forgo academic content. In other words, the same way a teacher can plan to have students learn a disciplinary skill, they can plan for students to experience joy while doing it. One priority doesn’t need to outweigh the other.”

“I would say to educators who want to prioritize getting kids up to speed academically over joy that the two are not mutually exclusive. They should think about them as mutually reinforcing,” he says. “Not only do joy and academic rigor go hand in hand, but tactful educators plan to ensure both happen in tandem.” He noted that Gholdy Muhammad’s framework outlined in her book Cultivating Genius includes five pillars to consider when planning lessons, and joy is one of them. “An example is children’s museums, which offer learning opportunities that center play and fun. Exhibit curators plan with joy and excitement at the center of their learning design, but they don’t forgo academic content. In other words, the same way a teacher can plan to have students learn a disciplinary skill, they can plan for students to experience joy while doing it. One priority doesn’t need to outweigh the other.”

He says this is especially important for students who experience “compounding killjoys” — students who “live with circumstances and experiences that make it very difficult to be joyful. Some big picture joy killers include poverty, racism, social isolation, and concrete realities that stem from racial, social, and economic injustice such as hunger and food insecurity, housing insecurity, exposure to violence, health ailments, and living in a household or community where adults experience chronic stress. The more of these killjoys that students experience, the more concerned educators should be about using learning as a means to cultivate joy.”

For example, he says that if students don’t have access to safe green space, recess should become a priority. If they experience conflict with relationships in their lives, educators can create learning scenarios that are collaborative, “which provide opportunities to find joy in working with people.”

Keeping this in mind, Sandra Nagy, Ed.M.’02, managing director of Future Design School, says any effort to get kids caught up and still feel joy needs to be intentional.

“In order for this important change to take hold in schools, there needs to be a space for joy,” she says. “That means balancing efforts to address learning loss with looking ahead to what we can do next and celebrating the way teachers proved their ability to innovate and adapt in the past two years.”

And Brooks says we can do something else to bring back joy that would once have been considered radical: We can slow down.

“We can engage with students where they are, whatever they’re interested in at the moment, because that’s the ‘stuff’ of the world they’re trying so hard to build normalcy from,” he says. “We can play with them on the field and court and laugh with them throughout the day. There will still be time for all that needs to be learned.”

Is joy still below the surface?

It’s all important — and it’s not all doom and gloom. Even tired educators say that below the frustrations, they see joy again.

“Given the circumstances, I have seen a lot of joy at school,” says Durney. “One of the many benefits of working with elementary-aged children is that they can find joy and humor in just about any activity.” Right before winter break, for example, they held an outdoor schoolwide activity where students were able to share their work and play games created by their peers and with parent involvement. “It felt like pre-pandemic times where we’d gather as a whole school community. The day ended with our principal jumping into the frigid waters at the M Street Beach in South Boston because as a school community we exceeded our fundraising goal. The smiles and laughter throughout the entire day were a great way to end the first stretch of the school year.”

Salch addressed burnout when students — and teachers — stopped using a diagnostic online program by creating a challenge where students would earn a popcorn party if they logged in for 10 of 15 days in December.

“We have a local chocolate factory that sells 10-gallon bags of popcorn for $6. We can feed a whole school for less than $15,” she says. “Students that earned the reward came out to the courtyard to eat a coffee filter full of popcorn and dance to Kidz Bop.”

She celebrates her teachers, too — even in small ways. “I do everything I can to keep my teachers joyful,” she says. “I write handwritten notes to them monthly thanking them or congratulating them on something they accomplished. I give random gifts of pens or stickies to show appreciation. I organize themed meetings that included engaging activities that show each other we are humans before we are our professions.”

Joshua Neufeld, a first-grade teacher at the American International School of Guangzhou in China and a participant in a Project Zero program in 2021, is part of a peer coaching network for international teachers called Positivity Playground. He found that regular staff socializing has helped morale.

“The pandemic has been challenging for everyone, and Positivity Playground reminded me that together, as colleagues, we can generate more positive emotions and manage negative emotions effectively.” With this in mind, Neufeld organized a weekly lunchtime tea party for his colleagues called Positvi-Tea. It’s a time for teachers to hang out and talk, he says, often about things other than school. “This is a time that energizes the participants and challenges them to continue the day with a positive outlook. I leave the meetings feeling recharged, viewing upcoming situations with a sense of realistic optimism.”

Beyond celebrations and gatherings, others say a focus on personalized learning and setting small, actionable steps (not just big lofty goals) can help bring joy back. Brooks says teachers and other educators can also pay more attention to self-care.

“I am striking a better work-life balance, taking time to be with my family and recharge,” he says. “Doing so allows me to be more fully present and increases the likelihood of finding and making joyful moments at work.” The same needs to be done for all educators. “It does not take anything extraordinary to bring joy back to the workplace of teachers. I would argue it comes down to acknowledging the difficulty of the work in these times, commiserating openly and honestly about these challenges, facing them together, and celebrating every small success of the professionals in the building. Impromptu conversations, dropping by to check in, and showing gratitude are a few other easy and regular ways to bring a sense of joy back to the workplace on a daily basis.”

With her ladybug stickers in hand and her joke book open and ready for the next meeting, Julia de la Torre is still tired, but she knows the joy at her school is there.

“Quite frankly, joy is the reason I come to work every day and why I love my job,” she says. “Pop your head into any classroom and you’ll see kids thriving, connecting, and enjoying school. They may have masks on, but you can see joy in their eyes and in their laughter. I’m always trying to remind my teachers that there is joy everywhere in schools, if you stop to look for it. It may be harder to find during these challenging times, but it’s the joy that keeps us coming back for more.”

Teacher Looping Promotes Student Success

Researchers have found that teacher looping is a key component in student success in school and beyond, as highlighted by a recent New York Times article. This practice involves students having one teacher for multiple years, which allows time for teachers to get to know each student personally, to understand their learning style, their strengths and challenges, and how to encourage them to do their best work. Waldorf Education has practiced teacher looping for over 100 years because we know that it provides the strongest foundation for each child’s future in both school and life.

This article was originally published by Adam Grant in the New York Times opinion section https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/22/opinion/education-us-teachers-looping.html

Which country has the best education system? Since 2000, every three years, 15-year-olds in dozens of countries have taken the Program for International Student Assessment — a standardized test of math, reading and science skills. On the inaugural test, which focused on reading, the top country came as a big surprise: tiny Finland. Finnish students claimed victory again in 2003 (when the focus was on math) and 2006 (when it was on science), all while spending about the same time on homework per week as the typical teenager in Shanghai does in a single day.

Just over a decade later, Europe had a new champion. Here, too, it wasn’t one of the usual suspects — not a big, wealthy country like Germany or Britain but the small underdog nation of Estonia. Since that time, experts have been searching for the secrets behind these countries’ educational excellence. They recently found one right here in the United States.

In North Carolina, economists examined data on several million elementary school students. They discovered a common pattern across about 7,000 classrooms that achieved significant gains in math and reading performance.

Those students didn’t have better teachers. They just happened to have the same teacher at least twice in different grades. A separate team of economists replicated the study with nearly a million elementary and middle schoolers in Indiana — and found the same results.

Every child has hidden potential. It’s easy to spot the ones who are already sparkling, but many students are uncut gems. When teachers stay with their students longer, they can see beyond the surface and recognize the brilliance beneath.

Instead of teaching a new cohort of students each year, teachers who practice “looping” move up a grade or more with their students. It can be a powerful tool. And unlike many other educational reforms, looping doesn’t cost a dime.

With more time to get to know each student personally, teachers gain a deeper grasp of the kids’ strengths and challenges. The teachers have more opportunities to tailor their instructional and emotional support to help all the students in the class reach their potential. They’re able to identify growth not only in peaks reached, but also in obstacles overcome. The nuanced knowledge they acquire about each student isn’t lost in the handoff to the next year’s teacher.

Finland and Estonia go even further. In both countries, it’s common for elementary schoolers to have the same teacher not just two years in a row but sometimes for up to six straight years. Instead of just specializing in their subjects, teachers also get to specialize in their students. Their role evolves from instructor to coach and mentor.

It didn’t occur to me until I read the research, but I was lucky to benefit from looping. My middle school piloted a program to keep students with the same two core teachers for all three years. When I struggled with spatial visualization in math, Mrs. Bohland didn’t question my aptitude. Having seen me ace a year of algebra, she knew I was an abstract thinker and taught me to use equations to identify the dimensions of shapes before drawing them in 3D. And after a few years of observing what fired me up in social studies and the humanities, Mrs. Minninger knew my interests well. She saw a common theme in my passions for analyzing character development in Greek mythology and anticipating counterarguments in mock trial — and suggested doing my year-end project on psychology. Thank you, Mama Minnie.

Most parents see the benefit of keeping their kids with the same coaches in sports and music for more than a year. Yet the American education system fails to do this with teachers, the most important coaches of all. Critics have long worried that following their students through a range of grades will prevent teachers from developing specialized skills appropriate to specific grade levels. Parents fret about rolling the dice on the same teacher more than once. What if my kid gets stuck with Mr. Snape or Miss Viola Swamp? But in the data, looping actually had the greatest upsides for less effective teachers — and lower-achieving students. Building an extended relationship gave them the opportunity to grow together.

The Finnish and Estonian education systems are far from perfect, and Finland’s PISA scores have dipped a bit in recent years. But both countries have done more than just achieve high rates of high performers — they’ve achieved some of the world’s lowest rates of low performers, with remarkably small performance gaps between schools and between richer and poorer students. Being disadvantaged is less of a disadvantage in Finland and Estonia than almost anywhere else.

Looping isn’t the only practice that makes a difference. Both Finland and Estonia have professionalized education systems — they often require master’s degrees for teachers, training them in evidence-based education practices and methods for interpreting ongoing research in the field. And teachers are entrusted with a great deal of autonomy. Whereas American kindergarten has become more like first grade, with more emphasis on spelling, writing and math, Finland and Estonia make learning fun with a play-based curriculum. Elementary schoolers typically get 15 minutes of recess for every 45 minutes of instruction. Teachers don’t have to waste time teaching to the test. And over the years, if students start to struggle, instead of labeling them as remedial or forcing them to repeat grades, schools in both countries offer early interventions focused on individual tutoring and extra support. That helps students get up to speed without being pulled off track.

Over the years, American students have consistently lagged behind two to three dozen countries on the PISA. A major factor in our lackluster results is the huge gap between our highest- and lowest-performing students. The U.S. education system is built around a culture of winner take all. Students who win the wealth lottery get to attend the best schools with the best teachers. Those who win the intelligence lottery may get to enroll in gifted-and-talented programs.

Great education systems create cultures of opportunity for all. They don’t settle for no child left behind; they strive to help every child get ahead. As the education expert Pasi Sahlberg writes, success is when “all students perform beyond expectations.” Finnish and Estonian schools don’t just invest in students who show early signs of high ability — they invest in every student regardless of apparent ability. And there are few better ways to do that than to keep students with teachers who have the time to get to know their abilities.

A Balanced Education Promotes Resilience

Waldorf education is an intentionally balanced approach to teaching with the goal of graduating happy, healthy, and resilient young people. We interweave academics, artistic activities, movement and outdoor time in a way that reduces stress and enhances learning. We provide rhythm for each day, season and year, which builds confidence and ensures that students feel secure. Social-emotional learning and problem solving are integrated throughout our curriculum so children develop the skills they need to thrive. We are a community where students feel seen, recognized, and challenged to do their best work and be their best selves.

This post is based on the findings of Ann S. Masten and Andrew J. Barnes in their National Library of Medicine paper, Resilience in Children: Developmental Perspectives. Please refer to the full paper for all citations.

Evidence continues to accumulate on the short- and long-term risks to health and well-being posed by adverse life experiences in children, particularly when adversities are prolonged, cumulative, or occurring during sensitive periods in early neurobiological development. Recent national and global examples include the growing concern about the impact of disasters, war, poverty, pandemics, climate change, and associated displacement on the global well-being of children. This confluence of threats to the present and future health of children motivates us to look at resilience and the factors that can support its development.

Resilience in humans can be broadly defined as the capacity to adapt successfully to challenges that threaten the function, survival, or future development of the individual. Resilience is also a feature of complex adaptive systems, including human individuals, but also families, economies, ecosystems, and organizations. This definition can also be applied to systems within an individual, such as the human immune system.

One of the most important implications of this definition is the idea that the resilience of a developing child is not circumscribed within the body and mind of that child. The capacity of an individual to adapt to challenges depends on their connections to other people and systems external to them through relationships and other processes. This includes their school environment and the relationships and experiences that are part of it.

For an individual person, resilience reflects all the adaptive capacity available at a given time in a given context that can be drawn upon to respond to current or future challenges facing the individual, through many different processes and connections. Resilience is not a trait, although individual differences in personality or cognitive skills clearly contribute to adaptive capacity. Supportive relationships play an enormous role in resilience across the lifespan. Close attachment bonds with a teacher or other caregiver and effective parenting can protect a young child in multiple ways that are not located “in the child”.

Human individuals have so much capacity for adaptation to adversity in part because their resilience depends on many interacting systems that co-evolved in biological and cultural evolution, conferring adaptive advantages. Moreover, children are often protected by multiple “back-up” systems, particularly embedded in their relationships with other people in their homes and communities.

Dose matters. Many studies of resilience have shown that the severity of exposure either to one extremely traumatic event or in the sense of cumulative risk, makes a difference. At the same time, these studies also show variation among individuals at similar levels of risk, some of whom are manifesting positive adaptation and development consistent with the presence of considerable resilience. In effect, these adaptive individuals are doing better than might be expected. These individuals motivated questions about how to account for their success and provided important clues for resilience science pertaining to the ongoing search for answers to the question of what makes a difference.

The shortlist of common resilience factors for child development shows that school environment can play an important role in helping children develop resilience, in particular the relationship development, teacher looping, intentional community, developmentally appropriate approach, and rhythms and rituals of a Waldorf education.

- Caring family, sensitive caregiving (nurturing family members)

- Close relationships, emotional security, belonging (family cohesion, belonging)

- Skilled parenting (skilled family management)

- Agency, motivation to adapt (active coping, mastery)Problem-solving skills, planning, executive function skills (collaborative problem-solving, family flexibility)

- Self-regulation skills, emotion regulation (co-regulation, balancing family needs)

- Self-efficacy, positive view of the self or identity (positive views of family and family identity)

- Hope, faith, optimism (hope, faith, optimism, positive family outlook)

- Meaning-making, belief life has meaning (coherence, family purpose, collective meaning-making)

- Routines and rituals (family routines and rituals, family role organization)

- Engagement in a well-functioning school

- Connections with well-functioning communities

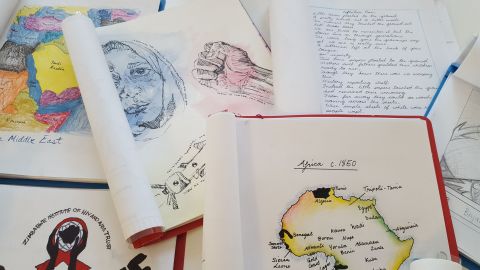

Learning is Multi-Sensory. Teaching Should Be Too.

Children learn in many different ways. That’s why it is so important for teachers to bring concepts through multiple senses. In Waldorf schools we teach science through stories as well as outdoors in nature and in the lab. We move, build, and even bake and eat our math. We teach literature through theater. We sing our history and languages. We teach this way so that our curriculum reaches more children, more deeply, in a way that they love and remember.

This article is an example of the ways the techniques and skills that have always been integral in Waldorf education are being recognized and incorporated into mainstream education.

How Multisensory Activities Enhance Reading Skills

Reading lessons can involve more than just our eyes and ears. Here’s how you can promote reading skills using all five senses.

This article was written by Laura DePriest and originally published on edutopia.org

As educators, we know what it is like to work with children who catch on quickly. The light bulb moments happen fairly easily for them, and they will likely progress despite what we do. We teach them their letter sounds and review flash cards a few times, and from then on those students know and apply them as they learn how to put those sounds together and read.

What can be done for children who are taught those same letter sounds, have seen those same flash cards countless times, and still can’t remember which letter makes which sound? Sometimes those children eventually catch on, but what if they don’t? Often, we assume those children aren’t as smart as the other children. But what if the issue is that their brains are wired in a particular way, and how they are taught needs to be adjusted instead of just repeating the same methods over and over again in the same way?

Recent research has shown that the brain can adapt and make new connections even into old age. Our brains are ever-changing as we take in new information and new experiences. When we discover that a child doesn’t respond to and recall information in the traditional ways, it is important to consider how the brain receives information. The brain is exposed to a stimulus (hearing a phone ring or tasting spaghetti), at which point it analyzes and evaluates the information. Our five senses (sight, touch, hearing, smell, and taste) send information to our brain, which is designed to recognize sensations, initiate behaviors, and store memories.

MULTISENSORY ACTIVITIES REINFORCE STRENGTHS AND IMPROVE WEAKNESSES

So, what does knowing how amazing our brains are mean for us as preschool and early elementary teachers? Well, we can consider very practical ways to incorporate multisensory activities into our literacy instruction. Multisensory activities benefit all students and can be implemented daily in our classrooms. However, the key is to use more than one sense at a time in order to cement the concept. A sight-based activity alone isn’t enough; pair visual learning activities with another type. When a lesson uses multiple senses at once, it reinforces students’ strengths and strengthens their weaknesses.

Sight: Students see stimuli with their eyes. In class, this includes labels on classroom furniture and other items, word walls, anchor charts, or big books. For individual students, it could be flash cards or graphic organizers like Read It, Build It, Write It. With this tool, teachers would dictate or display a word, and students would build the word using letter tiles, and then students would write the word.

Hearing: Students hear stimuli with their ears. This can include hearing letters and letter sounds as you say them, singing rhyming songs, and participating in read-alouds. Shared reading is also a powerful tool for developing literacy. As you read or your students listen to an audiobook, they can interact with the text by underlining sight words or circling the long or short vowels that they hear.

Touch: Students touch stimuli with their hands. This is perhaps the biggest missing piece in our classrooms, but this hands-on approach is crucial for young learners. Students can manipulate letter tiles as they spell words and blend sounds. They can form letters or words with kinetic sand or play-dough, or they can simply trace sandpaper letters with their fingers as they say and hear letter names and sounds.

Air-writing and arm tapping both activate gross motor skills. When air-writing, have your students stand and air-write a word with their dominant arm, moving from their shoulder to promote large muscle movement. When arm-tapping, students tap their arm using their dominant hand from left to right, starting at their shoulder. Saying each sound of the word as they tap reinforces the sounds. Then, have students make a sweeping motion across their arm as they say the whole word, as if underlining it.

The three previously mentioned senses blend seamlessly into the concept of literacy. Smell and taste, however, are much harder to incorporate because they don’t return the same response as knowing letters by sight, sound, and touch/writing. In order for students to best learn the intended literacy skill, the following sensory activities are most effective when they are used with at least one other activity from the previous group.

Smell: Students smell stimuli with their noses. For example, students can form their letters in scented shaving cream or use smelly markers when tracing or writing—perhaps making the letter S with a marker that smells like sweet strawberries. Younger children can read a scratch-and-sniff book, or even make their own book using smelly stickers.

Taste: Students taste stimuli with their mouths. This is the most popular type of activity. You can give students their own portion of letter-shaped crackers, cookies, cereal, or pudding to spell words—they can write letters with their fingers or spell words on crackers using Cheez Whiz. And then, of course, they get to eat their creation.

The best part about multisensory activities is that they usually feel like play to children. But because of what we know about how the brain makes connections and stores memories, these strategies are powerful in helping our children learn how to read. Multisensory literacy activities provide necessary intervention for the students who need it, while making learning more fun for all of our students.

Education in the Age of A.I.

How would you design an education system that helps students flourish in the face of changes to the nature of work brought on by artificial intelligence? The rise of ChatGPT and other AI large-language models have brought this question to the forefront of parents and educators' minds. Waldorf education is uniquely focused on developing children’s creativity, cultural competency, imagination and original thinking. We believe that teaching students to be able to articulate their own diverse viewpoints as well as their understanding of the material sets our students up for future success. In a future where AI-generated content relies on recombining existing work, our graduates' abilities to think critically, divergently, and creatively will serve them well.

ChatGPT Is Dumber Than You Think: Treat it like a toy, not a tool.

This article was originally written by Ian Bogost and published in The Atlantic

As a critic of technology, I must say that the enthusiasm for ChatGPT, a large-language model trained by OpenAI, is misplaced. Although it may be impressive from a technical standpoint, the idea of relying on a machine to have conversations and generate responses raises serious concerns.

First and foremost, ChatGPT lacks the ability to truly understand the complexity of human language and conversation. It is simply trained to generate words based on a given input, but it does not have the ability to truly comprehend the meaning behind those words. This means that any responses it generates are likely to be shallow and lacking in depth and insight.