Selecting a High School

Selecting a High School

Advice from Veteran Waldorf Educators

Choosing the right high school can feel like one of the most significant decisions a family will make in their child’s educational journey.

To bring clarity to this decision, we turned to two of our most experienced educators at the Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor: Margot Amrine, a longtime Waldorf teacher with over four decades of experience, and Dr. Siân Owen-Cruise, our former School Administrator, who has guided countless families through the high school selection process.

Today’s parents listen to and respect their children’s perspectives more than ever before- a positive shift in family dynamics. But as Margot reminds us, that doesn’t mean parents should surrender their leadership on big decisions.

“In our family we said that Waldorf Education for 9th and 10th grade was essential. At 11th grade, a different kind of maturity sets in; if our children had made compelling reasons to leave then, we would have considered. We never had these discussions!”

Dr. Owen-Cruise expands on this, acknowledging that social pressures play an outside role in an 8th Grader's thinking:

“It's natural for teenagers to focus on their peers and social dynamics when thinking about high school. As parents, we listen, we understand, and we take their feelings seriously- but ultimately, we need to lead this decision with wisdom and foresight.”

Dr. Owen-Cruise often frames the conversation with the rising student in the following way:

“Your parents will choose where you receive your high school education, with your input. YOU will choose where you go to college, with our parental input.”

Many families who have walked this path find that their children- whether they started in Waldorf Education or joined from another school-ultimately express gratitude that their parents guided this decision with their long-term development in mind.

Here are some other helpful tips and information when thinking about our own High School:

Waldorf Graduates Pursue Meaningful Careers

“Will My Child Succeed After Waldorf High School? The Research Says Yes” - Blog Article

Parents often ask: Does a Waldorf education prepare students for college, careers, and beyond? The answer is a resounding yes. Studies show that Waldorf graduates not only attend college at high rates but also excel in fields like science, medicine, law, and technology. Employers and universities consistently praise their ability to think critically, communicate effectively, and adapt to a changing world. Want to know why? This article dives into the research and real-world successes of our alumni.

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

"The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens" - Blog Article

In an age where screens dominate every aspect of life, imagine a school where students engage in real conversations, dive into hands-on projects, and focus fully in class—without the pull of notifications. Our phone-free policy isn’t just a rule; it’s a game-changer. See how it shapes our students’ social and academic lives!

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

The Joy of a Phone-Free School: How Our Students Thrive Without Screens

Imagine a typical school day where students, between classes and during breaks, are glued to their smartphones—scrolling through social media, playing games, or texting. Conversations are sparse, eye contact is minimal, and the vibrant energy of youthful interaction seems subdued. Now, contrast this with a school environment where smartphones are set aside: students engage in lively face-to-face discussions, participate in spontaneous games, and immerse themselves fully in classroom activities without the constant pull of notifications. This is the reality we’ve cultivated at Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, embracing a phone-free policy that fosters genuine connections and holistic development.

The Deeper Engagement of Phone-Free Education

At our school, we’ve observed that removing smartphones from the school day does more than just eliminate distractions—it rekindles a deeper, more meaningful engagement among students. Freed from screens, students rediscover the joy of direct communication, collaborative problem-solving, and hands-on learning. This environment aligns seamlessly with the principles of Waldorf education, emphasizing experiential learning and nurturing the whole child.

We Are Phone-Free, Not Tech-Free

While our school maintains a phone-free environment during school hours, we are not devoid of technology. In fact, our curriculum incorporates technology in age-appropriate ways to ensure students are prepared for the digital world:

• Middle School: Students are introduced to computers and the internet in an intentional way that supports learning. Additionally, our middle school robotics club fosters interest in technology and engineering through hands-on projects. https://www.steinerschool.org/programs/extracurricular-activities.cfm

• High School: Our state-of-the-art computer lab facilitates courses in coding, digital literacy, and other computer science subjects. We also have an active high school robotics club where students collaborate on competitive projects that develop real-world problem-solving skills. https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-education.cfm

Many of our graduates go on to thrive in technology fields, excelling in computer science, engineering, and data analysis. Research shows that Waldorf graduates develop strong interdisciplinary thinking skills that prepare them for success in fields that require both creativity and technical expertise.

Leading the Way in Ann Arbor

Our commitment to a phone-free school day positions us as pioneers in the Ann Arbor educational community. While some other local schools have implemented partial restrictions, our comprehensive approach ensures that students remain unplugged throughout the day—including breaks and transitions between classes.

Several Ann Arbor schools are recognizing the value of limiting phone use:

• Forsythe Middle School and Tappan Middle School both require students to keep phones in lockers during school hours. https://forsythe.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy, https://tappan.a2schools.org/our-school/cell-phone-policy

• Huron High School has introduced classroom phone storage policies in its Mathematics and English departments to help students stay focused. https://thehuronemery.com/9731/news/cell-phone-use-teacher-led-procedures-to-enrich-student-experience/

The Transformative Power of Disconnecting

The shift to a phone-free environment has yielded profound benefits:

• Enhanced Academic Focus: Without the allure of smartphones, students engage more deeply in lessons, leading to improved comprehension and retention.

• Strengthened Social Bonds: Face-to-face interactions during breaks and collaborative projects foster authentic relationships and empathy among students.

• Improved Mental Well-being: Reducing screen time has been linked to decreased anxiety and stress, allowing students to be more present and mindful.

Embracing a Connected Future Without Phones

As more schools recognize the value of limiting smartphone use, it’s evident that this movement is not about restricting technology but about reclaiming the essence of human connection and focused learning. By leading the way in this initiative, Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor not only adheres to the foundational principles of Waldorf education but also prepares students for careers in STEM, the arts, and beyond.

We invite families seeking a nurturing, distraction-free educational environment to join us in this journey, where students can truly engage with the world around them and develop into well-rounded individuals.

Explore the experiences of other schools with phone-free policies:

• “New data reveals shocking trend since school mobile phone ban”

- “The big smartphone school experiment”

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/inside-schools-ban-smartphones-6knb8qtfc

- “Cell phones hinder classroom learning. Texas should tell school districts to lock them up”

- "Waldorf Schools are Media Literacy Role Models"

https://www.steinerschool.org/about-us/waldorf-schools-are-media-literacy-role-models/

An Unhurried Childhood

A recent New York Times article highlighted the importance of giving children an unhurried childhood, without an overpacked schedule of extracurricular activities and excessive homework. The pressure on Gen Z to excel at a young age has led to decreased mental health and increasing struggles at school. Waldorf Education takes a balanced approach, with plenty of time for children to play and explore, while also providing a joyful and well-rounded education that instills essential life skills, sparks a lifelong love of learning, and prepares them for a successful future.

This article was written by Shalini Shankar and originally published on July 9, 2021 in the New York Times

A Packed Schedule Doesn’t Really ‘Enrich’ Your Child

When the extracurricular-industrial complex came to a grinding halt last spring, parents were left scrambling to fill vast hours of unscheduled time. Some activities moved to remote instruction but most were canceled, and keeping children engaged became the bane of parents’ existence. Understandably, screens became default child care for younger kids and social lifelines for older ones.

As American society reopens, going back to our children’s prepandemic activities looks like an enticing way to reintroduce upper-elementary through high-school-age kids to the outside world. For parents with economic means, it’s tempting to return to a full slate of language classes, sports, music lessons and other extracurriculars — a guilt-free plan to keep kids busy with “enriching” activities while we get our jobs done.

But I suggest pausing before filling up their calendars again. We should not simply return children to their hectic prepandemic schedules.

Certainly, some amount of extracurricular activity can offer a welcome break from screens and help children nurture interests. But for Generation Z, the over-scheduling of extracurricular activities has been bad for stress and mental health and even worse for widening racial gaps. Moreover, as I learned when I conducted anthropological research for my book “Beeline: What Spelling Bees Reveal About Generation Z’s New Path to Success,” it no longer consistently improves the prospects of the white middle-class kids for whom it was designed.

But what can parents do with our kids instead? The answer is simple, though not easy to carry out: We can teach them (and perhaps relearn ourselves) the value of unstructured time and greater civic participation.

This does not mean we should quit our day jobs and devote ourselves instead to endless hours of building forts and playing games. Exposing children to sports, music, art, programming or dance certainly has benefits — including physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and fun — but there are also good reasons to give children time to be bored. Not least of these is it forces them to figure out a way to entertain themselves.

For many kids today, scheduled time and down time on their screens are the only states of being. Paradoxically, scheduled unstructured time could address this. Cooking, reading a book, art projects and neighborhood walks are unlikely to completely replace screens, but routinizing blocks of time for these self-sustaining activities each day or several times a week could introduce children and teenagers to new pleasures, and at the very least invite calmness.

Gen Z acutely feels the pressure to be accomplished at a younger age. As kids take on a wider range of challenging activities younger, a trend that began with millennials but has grown to steroidal levels, the criteria for standing out in the college admissions process have shot up accordingly. It’s no wonder kids are stressed out.

The Slacker Generation, an initially disparaging label that Gen Xers have reclaimed, did not have to build a childhood résumé brimming with skills, expertise and accolades to get into college. Now many of these former slackers are parents worried about whether their kids are doing enough to stay competitive in college admissions and the job market. Those who can afford it feel pressure to pad their kids’ résumés as much as they can. A 2019 survey found that more than a quarter of “sports parents” spent upward of $500 per month, with some spending over $1,000 and jeopardizing their retirement savings.

But it’s clear by now that all this expensive enrichment won’t ensure kids’ success. Despite middle- and upper-class millennials mortgaging their childhood to get into college and then toiling through early adulthood in unpaid internships, they are unable to acquire the levels of economic and social security still held by their baby boomer parents.

Perhaps that’s why Gen Z has shown astute awareness of the dangers of overwork, with some high-profile Zoomers demonstrating acts of radical self-preservation. The Gen Z tennis star Naomi Osaka, for example, recently chose to prioritize her well-being over her career’s demands when she dropped out of the French Open after officials fined her for declining to participate in its post-match news conferences. Gen Z seems to have accepted that no matter how much you love your job, your job won’t love you back. Their parents — Gen Xers and even older millennials — were late to this lesson, and if they learned it at all, it was often only when they hit a wall with burnout.

Of course, preparing children for college and the job market is not the only goal of parents shelling out for guitar lessons or robot-making labs. Parents are also eager to expose their children to different ways of using their minds and bodies in the hope that they’ll discover passions that could become vocations, or simply lifelong joys. One passion that’s worth trying to instill is civic participation.

As parents, we can reinforce the importance of caring beyond one’s own success. Taking your kids to volunteer or to protest injustices they see in the world are good ways to show them what it looks like to give back and replenish. The human and nonhuman connections they will make at food pantries and animal shelters can help kids cultivate empathy — itself a valuable skill for navigating life — while offsetting the anxiety footprint caused by today’s inflated standards for success.

It might feel counterintuitive to deny your children the leg up in life that many extracurriculars promise, but it’s worth examining that impulse too. The pandemic has exacerbated existing socioeconomic disparities, especially along racial lines. With widening wealth gaps, there will be even fewer opportunities to prioritize extracurricular activities for low-income kids. Rethinking the value of a packed calendar offers a concrete opportunity to narrow the racial and economic gaps between privileged and underprivileged kids.

Replacing video games with nature walks might not make you the most popular parent. Your kids may complain a little (or a lot) about losing some of their organized fun, since boredom is a feeling they’ve rarely experienced. But they’ll figure it out.

Pushing Academics into Preschool Can Be Harmful

A comprehensive study finds significant drawbacks to pushing academics as early as in preschool. Researchers found that any initial academic gains were quickly erased, and children who attended academic-focused Pre-K were actually behind their peers in elementary and middle school. Another troubling finding was that students who experienced early academic pressure showed dramatic increases in behavioral issues later on. In Waldorf education, we focus on what is developmentally appropriate for each age group, understanding that preschool-age children especially need play, movement, and art, which are all critical to social-emotional health and future academic success.

This article was originally published by Anya Kamenetz on NPR.org

A top researcher says it's time to rethink our entire approach to preschool

Dale Farran has been studying early childhood education for half a century. Yet her most recent scientific publication has made her question everything she thought she knew.

"It really has required a lot of soul-searching, a lot of reading of the literature to try to think of what were plausible reasons that might account for this."

And by "this," she means the outcome of a study that lasted more than a decade. It included 2,990 low-income children in Tennessee who applied to free, public prekindergarten programs. Some were admitted by lottery, and the others were rejected, creating the closest thing you can get in the real world to a randomized, controlled trial — the gold standard in showing causality in science.

Farran and her co-authors at Vanderbilt University followed both groups of children all the way through sixth grade. At the end of their first year, the kids who went to pre-K scored higher on school readiness — as expected.

But after third grade, they were doing worse than the control group. And at the end of sixth grade, they were doing even worse. They had lower test scores, were more likely to be in special education, and were more likely to get into trouble in school, including serious trouble like suspensions.

"Whereas in third grade we saw negative effects on one of the three state achievement tests, in sixth grade we saw it on all three — math, science and reading," says Farran. "In third grade, where we had seen effects on one type of suspension, which is minor violations, by sixth grade we're seeing it on both types of suspensions, both major and minor."

That's right. A statewide public pre-K program, taught by licensed teachers, housed in public schools, had a measurable and statistically significant negative effect on the children in this study.

Farran hadn't expected it. She didn't like it. But her study design was unusually strong, so she couldn't easily explain it away.

"This is still the only randomized controlled trial of a statewide pre-K, and I know that people get upset about this and don't want it to be true."

Why it's a bad time for bad news

It's a bad time for early childhood advocates to get bad news about public pre-K. Federally funded universal prekindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds has been a cornerstone of President Biden's social agenda, and there are talks about resurrecting it from the stalled-out "Build Back Better" plan. Preschool has been expanding in recent years and is currently publicly funded to some extent in 46 states. About 7 in 10 4-year-olds now attend some kind of academic program.

This enthusiasm has rested in part on research going back to the 1970s. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman, among others, showed substantial long-term returns on investment for specially designed and carefully implemented programs.

To put it crudely, policymakers and experts have touted for decades now that if you give a 4-year-old who is growing up in poverty a good dose of story time and block play, they'll be more likely to grow up to become a high-earning, productive citizen.

What went wrong in Tennessee

No study is the last word. The research on pre-K continues to be mixed. In May 2021, a working paper (not yet peer reviewed) came out that looked at Boston's pre-K program. The study was a similar size to Farran's, used a similar quasi-experimental design based on random assignment, and also followed up with students for years. This study found that the preschool kids had better disciplinary records and were much more likely to graduate from high school, take the SATs and go to college, though their test scores didn't show a difference.

Farran believes that, with a citywide program, there's more opportunity for quality control than in her statewide study. Boston's program spent more per student, and it also was mixed-income, whereas Tennessee's program is for low-income kids only.

So what went wrong in Tennessee? Farran has some ideas — and they challenge almost everything about how we do school. How teachers are prepared, how programs are funded and where they are located. Even something as simple as where the bathrooms are.

In short, Farran is rethinking her own preconceptions, which are an entire field's preconceptions, about what constitutes quality pre-K.

Do kids in poverty deserve the same teaching as rich kids?

"One of the biases that I hadn't examined in myself is the idea that poor children need a different sort of preparation from children of higher-income families."

She's talking about drilling kids on basic skills. Worksheets for tracing letters and numbers. A teacher giving 10-minute lectures to a whole class of 25 kids who are expected to sit on their hands and listen, only five of whom may be paying any attention.

"Higher-income families are not choosing this kind of preparation," she explains. "And why would we assume that we need to train children of lower-income families earlier?"

Farran points out that families of means tend to choose play-based preschool programs with art, movement, music and nature. Children are asked open-ended questions, and they are listened to.

This is not what Farran is seeing in classrooms full of kids in poverty, where "teachers talk a lot, but they seldom listen to children." She thinks that part of the problem is that teachers in many states are certified for teaching students in prekindergarten through grade 5, or sometimes even pre-K-8. Very little of their training focuses on the youngest learners.

So another major bias that she's challenging is the idea that teacher certification equals quality. "There have been three very large studies, the latest one in 2018, which are not showing any relationship between quality and licensure."

Putting a bubble in your mouth

In 2016, Farran published a study based on her observations of publicly funded Tennessee pre-K classrooms similar to those included in this paper. She found then that the largest chunk of the day was spent in transition time. This means simply moving kids around the building.

Partly this is an architectural problem. Private preschools, even home-based day cares, tend to be laid out with little bodies in mind. There are bathrooms just off the classrooms. Children eat in, or very near, the classroom, too. And there is outdoor play space nearby with equipment suitable for short people.

Putting these same programs in public schools can make the whole day more inconvenient.

"So if you're in an older elementary school, the bathroom is going to be down the hall. You've got to take your children out, line them up and then they wait," Farran says. "And then, if you have to use the cafeteria, it's the same thing. You have to walk through the halls, you know: 'Don't touch your neighbor, don't touch the wall, put a bubble in your mouth because you have to be quiet.' "

One of Farran's most intriguing conjectures is that this need for control could explain the extra discipline problems seen later on in her most recent study.

"I think children are not learning internal control. And if anything, they're learning sort of an almost allergic reaction to the amount of external control that they're having, that they're having to experience in school."

In other words, regularly reprimanding kids for doing normal kid stuff at 4 years old, even suspending them, could backfire down the road as children experience school as a place of unreasonable expectations.

We know from other research that the control of children's bodies at school can have disparate racial impact. Other studies have suggested that Black children are disciplined more often in preschool, as they are in later grades. Farran's study, where 70% of the kids were white, found interactions between race, gender, and discipline problems, but no extra effect of attending preschool was detected.

Where to go from here

The United States has a child care crisis that COVID-19 both intensified and highlighted. Progressive policymakers and advocates have tried for years to expand public support for child care by "pushing it down" from the existing public school system, using the teachers and the buildings.

Farran praises the direction that New York City, for one, has taken instead: a "mixed-delivery" program with slots for 3- and 4-year-olds. Some kids attend free public preschool in existing nonprofit day care centers, some in Head Start programs and some in traditional schools.

But the biggest lesson Farran has drawn from her research is that we've simply asked too much of pre-K, based on early results from what were essentially showcase pilot programs. "We tend to want a magic bullet," she says.

"Whoever thought that you could provide a 4-year-old from an impoverished family with 5 1/2 hours a day, nine months a year of preschool, and close the achievement gap, and send them to college at a higher rate?" she asks. "I mean, why? Why do we put so much pressure on our pre-K programs?"

We might actually get better results, she says, from simply letting little children play.

The Value of an Unhurried Childhood

A recent New York Times article highlighted the importance of giving children an unhurried childhood, without an overpacked schedule of extracurricular activities and excessive homework. The pressure on Gen Z to excel at a young age has led to decreased mental health and increasing struggles at school. Waldorf Education takes a balanced approach, with plenty of time for children to play and explore, while also providing a joyful and well-rounded education that instills essential life skills, sparks a lifelong love of learning, and prepares them for a successful future.

This article was written by Shalini Shankar and originally published on July 9, 2021 in the New York Times

A Packed Schedule Doesn’t Really ‘Enrich’ Your Child

When the extracurricular-industrial complex came to a grinding halt last spring, parents were left scrambling to fill vast hours of unscheduled time. Some activities moved to remote instruction but most were canceled, and keeping children engaged became the bane of parents’ existence. Understandably, screens became default child care for younger kids and social lifelines for older ones.

As American society reopens, going back to our children’s prepandemic activities looks like an enticing way to reintroduce upper-elementary through high-school-age kids to the outside world. For parents with economic means, it’s tempting to return to a full slate of language classes, sports, music lessons and other extracurriculars — a guilt-free plan to keep kids busy with “enriching” activities while we get our jobs done.

But I suggest pausing before filling up their calendars again. We should not simply return children to their hectic prepandemic schedules.

Certainly, some amount of extracurricular activity can offer a welcome break from screens and help children nurture interests. But for Generation Z, the over-scheduling of extracurricular activities has been bad for stress and mental health and even worse for widening racial gaps. Moreover, as I learned when I conducted anthropological research for my book “Beeline: What Spelling Bees Reveal About Generation Z’s New Path to Success,” it no longer consistently improves the prospects of the white middle-class kids for whom it was designed.

But what can parents do with our kids instead? The answer is simple, though not easy to carry out: We can teach them (and perhaps relearn ourselves) the value of unstructured time and greater civic participation.

But what can parents do with our kids instead? The answer is simple, though not easy to carry out: We can teach them (and perhaps relearn ourselves) the value of unstructured time and greater civic participation.

This does not mean we should quit our day jobs and devote ourselves instead to endless hours of building forts and playing games. Exposing children to sports, music, art, programming or dance certainly has benefits — including physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and fun — but there are also good reasons to give children time to be bored. Not least of these is it forces them to figure out a way to entertain themselves.

For many kids today, scheduled time and down time on their screens are the only states of being. Paradoxically, scheduled unstructured time could address this. Cooking, reading a book, art projects and neighborhood walks are unlikely to completely replace screens, but routinizing blocks of time for these self-sustaining activities each day or several times a week could introduce children and teenagers to new pleasures, and at the very least invite calmness.

Gen Z acutely feels the pressure to be accomplished at a younger age. As kids take on a wider range of challenging activities younger, a trend that began with millennials but has grown to steroidal levels, the criteria for standing out in the college admissions process have shot up accordingly. It’s no wonder kids are stressed out.

The Slacker Generation, an initially disparaging label that Gen Xers have reclaimed, did not have to build a childhood résumé brimming with skills, expertise and accolades to get into college. Now many of these former slackers are parents worried about whether their kids are doing enough to stay competitive in college admissions and the job market. Those who can afford it feel pressure to pad their kids’ résumés as much as they can. A 2019 survey found that more than a quarter of “sports parents” spent upward of $500 per month, with some spending over $1,000 and jeopardizing their retirement savings.

But it’s clear by now that all this expensive enrichment won’t ensure kids’ success. Despite middle- and upper-class millennials mortgaging their childhood to get into college and then toiling through early adulthood in unpaid internships, they are unable to acquire the levels of economic and social security still held by their baby boomer parents.

Perhaps that’s why Gen Z has shown astute awareness of the dangers of overwork, with some high-profile Zoomers demonstrating acts of radical self-preservation. The Gen Z tennis star Naomi Osaka, for example, recently chose to prioritize her well-being over her career’s demands when she dropped out of the French Open after officials fined her for declining to participate in its post-match news conferences. Gen Z seems to have accepted that no matter how much you love your job, your job won’t love you back. Their parents — Gen Xers and even older millennials — were late to this lesson, and if they learned it at all, it was often only when they hit a wall with burnout.

Of course, preparing children for college and the job market is not the only goal of parents shelling out for guitar lessons or robot-making labs. Parents are also eager to expose their children to different ways of using their minds and bodies in the hope that they’ll discover passions that could become vocations, or simply lifelong joys. One passion that’s worth trying to instill is civic participation.

Of course, preparing children for college and the job market is not the only goal of parents shelling out for guitar lessons or robot-making labs. Parents are also eager to expose their children to different ways of using their minds and bodies in the hope that they’ll discover passions that could become vocations, or simply lifelong joys. One passion that’s worth trying to instill is civic participation.

As parents, we can reinforce the importance of caring beyond one’s own success. Taking your kids to volunteer or to protest injustices they see in the world are good ways to show them what it looks like to give back and replenish. The human and nonhuman connections they will make at food pantries and animal shelters can help kids cultivate empathy — itself a valuable skill for navigating life — while offsetting the anxiety footprint caused by today’s inflated standards for success.

It might feel counterintuitive to deny your children the leg up in life that many extracurriculars promise, but it’s worth examining that impulse too. The pandemic has exacerbated existing socioeconomic disparities, especially along racial lines. With widening wealth gaps, there will be even fewer opportunities to prioritize extracurricular activities for low-income kids. Rethinking the value of a packed calendar offers a concrete opportunity to narrow the racial and economic gaps between privileged and underprivileged kids.

Replacing video games with nature walks might not make you the most popular parent. Your kids may complain a little (or a lot) about losing some of their organized fun, since boredom is a feeling they’ve rarely experienced. But they’ll figure it out.

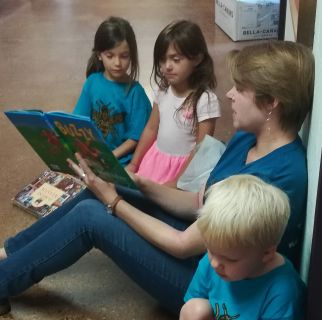

How Kids Fall In Love With Reading

Since the 1980’s there has been a double digit decline in the number of kids who say they read for pleasure. What accounts for this? A standardized test-driven shift towards textual analysis, where students increasingly are asked to dissect small and out-of-context segments of text, and where reading aloud and reading entire stories have fallen by the wayside. In Waldorf education, we take the opposite approach. We start with engaging the children’s imaginations through storytelling and reading aloud. We know that love of reading starts with a love of stories, and that a love of reading opens up a lifetime love of learning.

This article was originally published in The Atlantic in March, 2023

These days, when I explain to a fellow parent that I write novels for children in fifth through eighth grades, I am frequently treated to an apologetic confession: “My childdoesn’t read, at least not the way I did.” I know exactly how they feel—my tween and teen don’t read the way I did either. When I was in elementary school, I gobbled up everything: haunting classics such as The Witch of Blackbird Pond and gimmicky series such as the Choose Your Own Adventure books. By middle school, I was reading voluminous adult fiction like the works of Louisa May Alcott and J. R. R. Tolkien. Not every child is—or was—this kind of reader. But what parents today are picking up on is that a shrinking number of kids are reading widely and voraciously for fun.

These days, when I explain to a fellow parent that I write novels for children in fifth through eighth grades, I am frequently treated to an apologetic confession: “My childdoesn’t read, at least not the way I did.” I know exactly how they feel—my tween and teen don’t read the way I did either. When I was in elementary school, I gobbled up everything: haunting classics such as The Witch of Blackbird Pond and gimmicky series such as the Choose Your Own Adventure books. By middle school, I was reading voluminous adult fiction like the works of Louisa May Alcott and J. R. R. Tolkien. Not every child is—or was—this kind of reader. But what parents today are picking up on is that a shrinking number of kids are reading widely and voraciously for fun.

The ubiquity and allure of screens surely play a large part in this—most American children have smartphones by the age of 11—as does learning loss during the pandemic. But this isn’t the whole story. A survey just before the pandemic by the National Assessment of Educational Progress showed that the percentages of 9- and 13-year-olds who said they read daily for fun had dropped by double digits since 1984. I recently spoke with educators and librarians about this trend, and they gave many explanations, but one of the most compelling—and depressing—is rooted in how our education system teaches kids to relate to books.

What I remember most about reading in childhood was falling in love with characters and stories; I adored Judy Blume’s Margaret and Beverly Cleary’s Ralph S. Mouse. In New York, where I was in public elementary school in the early ’80s, we did have state assessments that tested reading level and comprehension, but the focus was on reading as many books as possible and engaging emotionally with them as a way to develop the requisite skills. Now the focus on reading analytically seems to be squashing that organic enjoyment. Critical reading is an important skill, especially for a generation bombarded with information, much of it unreliable or deceptive. But this hyperfocus on analysis comes at a steep price: The love of books and storytelling is being lost.

This disregard for story starts as early as elementary school. Take this requirement from the third-grade English-language-arts Common Core standard, used widely across the U.S.: “Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, distinguishing literal from nonliteral language.” There is a fun, easy way to introduce this concept: reading Peggy Parish’s classic, Amelia Bedelia, in which the eponymous maid follows commands such as “Draw the drapes when the sun comes in” by drawing a picture of the curtains. But here’s how one educator experienced in writing Common Core–aligned curricula proposes this be taught: First, teachers introduce the concepts of nonliteral and figurative language. Then, kids read a single paragraph from Amelia Bedelia and answer written questions.

For anyone who knows children, this is the opposite of engaging: The best way to present an abstract idea to kids is by hooking them on a story. “Nonliteral language” becomes a whole lot more interesting and comprehensible, especially to an 8-year-old, when they’ve gotten to laugh at Amelia’s antics first. The process of meeting a character and following them through a series of conflicts is the fun part of reading. Jumping into a paragraph in the middle of a book is about as appealing for most kids as cleaning their room.

But as several educators explained to me, the advent of accountability laws and policies, starting with No Child Left Behind in 2001, and accompanying high-stakes assessments based on standards, be they Common Core or similar state alternatives, has put enormous pressure on instructors to teach to these tests at the expense of best practices. Jennifer LaGarde, who has more than 20 years of experience as a public-school teacher and librarian, described how one such practice—the class read-aloud—invariably resulted in kids asking her for comparable titles. But read-alouds are now imperiled by the need to make sure that kids have mastered all the standards that await them in evaluation, an even more daunting task since the start of the pandemic. “There’s a whole generation of kids who associate reading with assessment now,” LaGarde said.

By middle school, not only is there even less time for activities such as class read-alouds, but instruction also continues to center heavily on passage analysis, said LaGarde, who taught that age group. A friend recently told me that her child’s middle-school teacher had introduced To Kill a Mockingbird to the class, explaining that they would read it over a number of months—and might not have time to finish it. “How can they not get to the end of To Kill a Mockingbird?” she wondered. I’m right there with her. You can’t teach kids to love reading if you don’t even prioritize making it to a book’s end. The reward comes from the emotional payoff of the story’s climax; kids miss out on this essential feeling if they don’t reach Atticus Finch’s powerful defense of Tom Robinson in the courtroom or never get to solve the mystery of Boo Radley.

Not every teacher has to focus on small chunks of literature at the expense of the whole plot, of course. But as a result of this widespread message, that reading a book means analyzing it within an inch of its life, the high/low dichotomy that has always existed in children’s literature (think The Giver versus the Goosebumps series) now feels even wider. “What do you call your purely fun books for kids?” a middle-grade author recently asked on Twitter. A retired fifth-grade teacher seemed flummoxed by the question: “I never called a book a fun book,” she wrote. “I’d say it’s a great book, a funny book, a touching book … So many books ARE fun!!”

And yet the idea that reading all kinds of books is enjoyable is not the one kids seem to be receiving. Even if most middle schoolers have read Diary of a Wimpy Kid, it’s not making them excited to move on to more challenging fare. Longer books, for example, are considered less “fun”; in addition, some librarians, teachers, and parents are noticing a decline in kids’ reading stamina after the disruption of the pandemic. You can see these factors at play in a recent call for shorter books. But one has to wonder whether this is also the not-entirely-unsurprising outcome of having kids interact with literature in paragraph-size bites.

We need to meet kids where they are; for the time being, I am writing stories that are shorter and less complex. At the same time, we need to get to the root of the problem, which is not about book lengths but the larger educational system. We can’t let tests control how teachers teach: Close reading may be easy to measure, but it’s not the way to get kids to fall in love with storytelling. Teachers need to be given the freedom to teach in developmentally appropriate ways, using books they know will excite and challenge kids. (Today, with more diverse titles and protagonists available than ever before, there’s also a major opportunity to spark joy in a wider range of readers.) Kids should be required to read more books, and instead of just analyzing passages, they should be encouraged to engage with these books the way they connect with “fun” series, video games, and TV shows.

Young people should experience the intrinsic pleasure of taking a narrative journey, making an emotional connection with a character (including ones different from themselves), and wondering what will happen next—then finding out. This is the spell that reading casts. And, like with any magician’s trick, picking a story apart and learning how it’s done before you have experienced its wonder risks destroying the magic.

Waldorf Schools are Media Literacy Role Models

Waldorf education emphasizes thoughtful, intentional and developmentally appropriate technology use. We advocate for an experiential, relationship-based approach in early education, followed by a curriculum for older students that helps them understand tech as a tool, and engages them in conversations around digital ethics, privacy, media literacy, and balanced use of social media and technology. Our approach gives Waldorf graduates the tools and knowledge they need to be independent, creative, and ethical digital citizens. At Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor, Cyber Civics is a required class in grades 6-8 and Computer Science and Programming are taught at the high school level.

This post was written by Soni Albright and originally published on cybercivics.com

As we celebrate Media Literacy Week… it’s hard to believe that Waldorf schools in North America have been leading the way when it comes to Media Literacy education.

What’s that? Waldorf schools and “Media” Literacy?

Do you mean those schools that are notoriously low-tech, and focus on things like face-to-face communication, hands-on learning, the great outdoors, and an art/music/movement integrated curriculum?

Yep, those schools!

Cyber Civics was founded at a public charter Waldorf school —Journey School—in 2010. Since its inception, most Waldorf schools (private and public) in North America, and many more internationally, have adopted the Cyber Civics program in their schools, and the vast majority have been teaching the lessons—which include digital citizenship, information literacy, and media literacy— since 2017.

Fast forward to 2021. The United States and most of the world is just now talking about the ‘need for digital citizenship’ and the importance of ‘educating our youth’ about media use, misinformation, balance and wellness and, most importantly, how to use tech ethically and wisely.

People worldwide are asking themselves “How do we control this Pandora’s Box after the pandemic? What can we do to help our kids help themselves in the digital landscape?”

All the while, Waldorf schools have been quietly holding this conversation with intentionality and patience: asking families to be thoughtful, mindful, discerning, and slow with media access for children. Not to deprive them, but rather to give children the gift of childhood—the endless opportunities that come with downtime, boredom, and unscheduled freedom. To favor face-to-face interactions over abstract experiences. To work on self-regulation, problem solving, physical movement, and social-emotional regulation.

By the time Waldorf students get to middle school, even though many aren’t using digital media at the same level as average kids their age, most are participating in weekly Cyber Civics lessons ranging from simple concepts such as what it means to be a citizen in any community and how to apply that to the digital world to more advanced topics such as: privacy and personal information, identifying misinformation, reading visual images, recognizing stereotypes and media representations, and ethical thinking in future technologies.

While many middle school students know their way around the device / app / platform, they haven’t been trained much in ethics, privacy, balance, and the decision-making aspects actually needed to survive and thrive in the digital age during adolescence.

We are so grateful for all the Waldorf schools that recognized the need for this important curriculum years ago, and who have grown with us over the years. We have learned with you, about our young people and what they need from us as examples and digital citizens.

Thank you for paving the way for this curriculum to be brought to so many other schools and community groups beyond the Waldorf sphere—public and private schools... Catholic, Hebrew, Montessori, and more.

And please take a bow for being the Media Literacy role models the world so desperately needs.

Talking With our Littlest Students About Race

Adapted from Acorn Hill Waldorf Kindergarten

Children are constantly picking up on what is OK to talk about, what is off limits, and how adults react to the topic. Here's how to begin or continue a discussion about race with your child.

Like many other topics, race can be challenging for adults to discuss among themselves, let alone with their children. But while open dialogue about race is limited in our society, that doesn't mean you can't make decisions and set the tone for discussions about race in your home. Talking with young children about race is an opportunity - one you may or may not have experienced when you were growing up.

Some well-meaning parents feel if they do not address the topic of race, their children will be "color-blind." But the reality is that race does have meaning in our society. Your conversations with your child will depend on your own racial identity, the racial make-up of your family (immediate and extended), and your values regarding race—both those you express and those you imply.

Like other crucial conversations you might be beginning to have with your child right now, race discussions should start early and evolve as your child grows.

What They Understand

Kids under 24 months do not understand the adult meaning of race: the historical implications of it or how the history and current meaning of race affects our society, but babies and toddlers are beginning to notice differences in appearance. It might be that the child simply looks longer at or perhaps points to a person who looks different from the people she's most used to seeing in her everyday routines. During these moments, the child looks primarily to the adult to gauge their own interest and reaction—toddlers this young are still reliant on their parents' opinions and actions to shape their own. This goes without saying, but how you act around and discuss people from your own culture and other cultures is what your child will first consider appropriate. Toddlers internalize the beliefs of their family and immediate society, a process that will continue throughout their development.

Kids under 24 months do not understand the adult meaning of race: the historical implications of it or how the history and current meaning of race affects our society, but babies and toddlers are beginning to notice differences in appearance. It might be that the child simply looks longer at or perhaps points to a person who looks different from the people she's most used to seeing in her everyday routines. During these moments, the child looks primarily to the adult to gauge their own interest and reaction—toddlers this young are still reliant on their parents' opinions and actions to shape their own. This goes without saying, but how you act around and discuss people from your own culture and other cultures is what your child will first consider appropriate. Toddlers internalize the beliefs of their family and immediate society, a process that will continue throughout their development.

As the children grow, so does their awareness and their misconceptions about race. Studies have shown that by three years old, children are choosing playmates by race and by ages 4-6 their racial prejudices peak. By ages 5 and 6, children are already holding many of the viewpoints that the adults around them have on race. Not speaking to them about the topic means that they are making their own assumptions, and forming their own biases

What to Say

Say something! Your child's understanding of race begins both with what you will talk about and what you do not discuss. Children learn that when they ask a question about someone's race and they are shushed, it's not something they can discuss and is therefore taboo. Talking about race normalizes the topic and makes it less scary for kids.

As any parent who's caught their toddler staring at someone in the checkout aisle or pointing to a passerby in the mall will tell you, racial observations may be embarrassing. It really is important, though, for you to address your child's observations and take that moment to acknowledge the differences they are taking note of.

When your child points out (or later asks questions about) people with different skin color than his, address it. For example, if your child is white and asks why an African-American child's skin is brown, explain, "Grownups and kids have all different skin colors. Some have tan and some have brown." When possible, use accurate ethnicity language with your child: "She is white (or Caucasian)/African American (or black)/Latinx (or Hispanic)/Asian-American," etc.

When your child points out (or later asks questions about) people with different skin color than his, address it. For example, if your child is white and asks why an African-American child's skin is brown, explain, "Grownups and kids have all different skin colors. Some have tan and some have brown." When possible, use accurate ethnicity language with your child: "She is white (or Caucasian)/African American (or black)/Latinx (or Hispanic)/Asian-American," etc.

Though toddlers likely won't ask questions about race, children in preschool or grade school will have the vocabulary to articulate observations. Your child might ask why a person has skin a different color or hair a different texture than his. When he does make an observation or inquire about a race, answer the question and give correct information, which may mean doing some homework yourself. Think about and take responsibility for the stereotypes and assumptions we all have about race.

These are some basic ways you can prepare for a lifetime of conversations with your child about ethnicity and diversity

Self-reflect. Take some time and think about your own racial identity, the assumptions you hold, and what lessons you would like to teach your children about race. Talking with friends, family, and other parents can be really helpful. Look for other parents who are interested in open dialogue about race in their families. Talking with other adults will also give you clarity and increase your comfort level when answering questions if this is a challenge for you. Remember, this is often a scary process for adults. Understanding and challenging that fear will be helpful in conversations in your family.

Don't avoid the topic. Particularly in white families, some parents decide to not discuss racial differences. This reinforces that it is a taboo subject for your children. When you have had early conversations about appearances, for example, as your child gets older, you can also begin discussions about racism.

Don't avoid the topic. Particularly in white families, some parents decide to not discuss racial differences. This reinforces that it is a taboo subject for your children. When you have had early conversations about appearances, for example, as your child gets older, you can also begin discussions about racism.

Work on Empathy. Developing empathy comes from knowing your own feelings and beginning to understand feelings in others. How you interact with other people and respond to situations works on shaping that within your child. It may seem small and simple, but it is laying the foundation for how they treat, advocate for and think of others. Here are some Teaching Empathy Tips.

Look at your environment. Self-reflecting also means taking inventory of the images, stories and people that your child sees on a daily basis. Looking at your child’s toys, books, media influences, family, friends and neighborhood/community allows you to see areas for growth or conversation.

Read Books. Books are wonderful because they serve as windows into another’s world, reflections into your own, and give children the ability to connect with others. They also serve as good talking points for bringing up discussions about differences, injustice, and provide ways to celebrate and normalize diversity. Our Early Childhood Library offers a great selection of titles.

If you want to learn more about the Metaverse Development, please read our blog