Waldorf Graduates Pursue Meaningful Careers

Will My Child Succeed After Waldorf High School? The Research Says Yes

Choosing a high school is a critical decision, and parents often wonder: Will this education prepare my child for college, career, and life?

For families considering Waldorf high schools, this question is especially relevant. With experiential learning, seminar-style discussions, and an interdisciplinary curriculum, can Waldorf truly equip students for fields like medicine, law, technology, and business?

Decades of research say yes.

Waldorf Graduates Excel in Higher Education and Careers

A 60-year study (Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II, Mitchell & Gerwin, 2007) found that:

- 94% of Waldorf graduates attend college.

- 42% major in science-related fields—more than double the national average.

- Many earn advanced degrees in medicine, law, engineering, business, and the arts.

- Alumni thrive in fields ranging from finance and research to entrepreneurship and sustainability.

Waldorf Alumni Spotlight: Science in Action

After earning a degree in Earth Systems Engineering from the University of Michigan, Gavin Chensue ('06) joined the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps, leading critical climate studies worldwide.

"Steiner education gave me a taste of everything. When I needed direction in college, I remembered how much I loved studying weather and geology—and that led me to where I am today." - Gavin Chensue (RSSAA '06), Research Engineer at SRI International, Former NOAA Corps Officer

His story highlights how Waldorf graduates succeed in STEM, combining curiosity and real-world problem-solving to make a global impact.

Read the full studies:

- Survey of Waldorf Graduates, Phase II: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/research

- Into the World Study: https://www.waldorfeducation.org/graduate-outcomes

What Makes a Waldorf Education So Effective?

Contrary to the belief that test-driven education leads to success, research shows that employers and universities highly value graduates who:

✔ Think critically and independently

✔ Communicate clearly and persuasively

✔ Collaborate effectively

✔ Solve complex problems

✔ Adapt to a changing world

These are precisely the skills Waldorf high schools cultivate.

1. Depth Over Memorization: Lifelong Knowledge Retention

Rather than rote memorization, Waldorf fosters deep understanding:

- History is explored through primary sources and narratives.

- Science emphasizes hands-on experiments and independent research.

- Mathematics focuses on real-world application.

- Literature and philosophy encourage analytical discussions.

One employer noted:

“Waldorf students don’t just look for the right answer—they explore the why and how behind complex issues.”

2. Seminar-Style Learning Develops Exceptional Communicators

Waldorf emphasizes oral presentations, debates, and collaborative discussions, preparing graduates for leadership roles in law, finance, business, and medicine.

Dr. Ilan Safit, co-author of *Into the World*, states:

“We consistently hear that Waldorf graduates excel at teamwork and leadership. Their ability to articulate complex ideas is a major asset.”

A study from Da Vinci Waldorf School found that Waldorf students select careers based on values and passion rather than prestige or income.

Final Thoughts: The Research Speaks for Itself

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Professors and employers highlight Waldorf graduates’ intellectual curiosity and ability to think independently.

With strong college attendance rates, success across multiple professions, and the skills needed to navigate a complex world, one thing is clear:

Waldorf graduates don’t just succeed—they thrive.

Read more on Waldorf Graduates

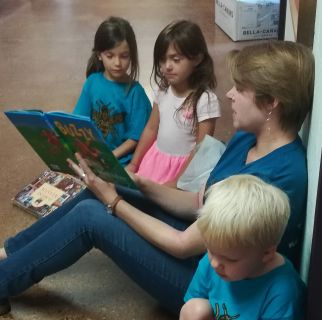

The Waldorf Approach to Reading

Could pushing kids to read too early be counterproductive? Studies have shown that academic demands on young children have increased significantly in the last few decades, with mixed results. Many children feel unnecessary stress in response to early academic pressure, with long-term negative effects. In the Waldorf approach, children build their foundation to reading and writing organically, learning letters and sounds through stories, songs, word games, and more. This low-stress, natural approach starts in preschool and is integrated into every subject, every day. Our story-first approach helps children feel excited, rather than pressured, to learn to read and write, and engages their natural curiosity and love of learning.

This article was originally published by Whitney Ballard on the Bored Teachers website.

Study Shows: Pushing Kids to Read Too Much, Too Early is Counterproductive

It’s no secret that there is a constant push to do MORE and be BETTER in education. It often feels like a never-ending competition. If your child performs well, you “should” push him or her to be better than their peers. Your school may perform well, but you “should” push for the best in the state. Your state may do well, but you “should” push to beat other regions. In terms of news, our country is “so far behind”. These not-so-subtle messages are pushing our students, teachers, and all other school personnel far beyond age-appropriate performance levels. It starts with reading. Exactly why are we pushing kids to read so early?

In fact, learning to read too early can actually be counterproductive. Studies show it can lead to a variety of problems including increased frustration, misdiagnosed disorders, and unnecessary time and money spent teaching kids skills they don’t even have the skillset to understand yet.

“Escalating Academic Demand in Kindergarten: Counterproductive Policies” is one study that exemplifies the reverse of pushing children to read before they are ready:

“Narrow emphasis on isolated reading and numeracy skills is detrimental even to the children who succeed and is especially harmful to children labeled as failures…academic demands in kindergarten and first grade are considerably higher today than 20 years ago and continue to escalate.”

While it may seem like our kids are being pushed to succeed, they are often pushed too hard. They eventually accept defeat because it becomes increasingly difficult for students to keep up with impossible standards. Once kids “fall behind” according to educational standards, it creates an “I’m not good enough” mentality. This often sticks with them through school. The early years are extremely important for building confidence and a positive attitude. Yet every year, we fill the early years with more requirements that are proven to be confidence-killers and negative reinforcements.

There are virtually zero studies that show proof that reading early actually helps kids succeed long-term.

From a secondary teacher’s perspective, I have never been able to tell which child learned to read first, or which child could recite their ABCs before they were 3 years old. I could, however, tell which students felt confident in his or her abilities. Likewise, I could tell which students struggled to believe in themselves and which students expected to fail. As a teacher, I worry that we are putting skills like reading above social skills and confidence-building.

I could, however, tell which students felt confident in his or her abilities. Likewise, I could tell which students struggled to believe in themselves and which students expected to fail. As a teacher, I worry that we are putting skills like reading above social skills and confidence-building.

The teacher part of me can see the long-term struggle, but the parent-of-young-kids part of me can see the current stress. It is extremely difficult not to buy into the hype—the kind that tells you your young children need every educational toy on the market. Society tells mamas (and daddies) that their children are falling behind in sneaky ways through the use of advertisements, social media, etc.

Parents are constantly seeing children praised for their outstanding achievements and are being asked to compare their own children with the ‘exception’, not the rule. Many kids WANT to accelerate the process and constantly learn MORE. That is perfectly fine. Many kids also want to take their sweet time. That is also perfectly fine.

No two kids are the same. And no two students are the same. No kid should be pushed too hard too early to do anything, including reading.

As a teacher, I am constantly reassuring parents that their children are on track, despite the constant “push” for more. And as a parent, I am constantly re-centering myself on the idea that our children are natural learners who learn more from the world around them at a young age. As a friend, I want to encourage you to research the lack of benefits of learning to read too early—and look to your child for cues on when he or she is actually ready.

What age is truly the right age to learn to read? It depends on the individual.

In the meantime, let’s focus on building confidence, fostering creativity, and allowing our young kids to learn in the ways that suit them best.

Learning is Multi-Sensory. Teaching Should Be Too.

Children learn in many different ways. That’s why it is so important for teachers to bring concepts through multiple senses. In Waldorf schools we teach science through stories as well as outdoors in nature and in the lab. We move, build, and even bake and eat our math. We teach literature through theater. We sing our history and languages. We teach this way so that our curriculum reaches more children, more deeply, in a way that they love and remember.

This article is an example of the ways the techniques and skills that have always been integral in Waldorf education are being recognized and incorporated into mainstream education.

How Multisensory Activities Enhance Reading Skills

Reading lessons can involve more than just our eyes and ears. Here’s how you can promote reading skills using all five senses.

This article was written by Laura DePriest and originally published on edutopia.org

As educators, we know what it is like to work with children who catch on quickly. The light bulb moments happen fairly easily for them, and they will likely progress despite what we do. We teach them their letter sounds and review flash cards a few times, and from then on those students know and apply them as they learn how to put those sounds together and read.

What can be done for children who are taught those same letter sounds, have seen those same flash cards countless times, and still can’t remember which letter makes which sound? Sometimes those children eventually catch on, but what if they don’t? Often, we assume those children aren’t as smart as the other children. But what if the issue is that their brains are wired in a particular way, and how they are taught needs to be adjusted instead of just repeating the same methods over and over again in the same way?

Recent research has shown that the brain can adapt and make new connections even into old age. Our brains are ever-changing as we take in new information and new experiences. When we discover that a child doesn’t respond to and recall information in the traditional ways, it is important to consider how the brain receives information. The brain is exposed to a stimulus (hearing a phone ring or tasting spaghetti), at which point it analyzes and evaluates the information. Our five senses (sight, touch, hearing, smell, and taste) send information to our brain, which is designed to recognize sensations, initiate behaviors, and store memories.

MULTISENSORY ACTIVITIES REINFORCE STRENGTHS AND IMPROVE WEAKNESSES

So, what does knowing how amazing our brains are mean for us as preschool and early elementary teachers? Well, we can consider very practical ways to incorporate multisensory activities into our literacy instruction. Multisensory activities benefit all students and can be implemented daily in our classrooms. However, the key is to use more than one sense at a time in order to cement the concept. A sight-based activity alone isn’t enough; pair visual learning activities with another type. When a lesson uses multiple senses at once, it reinforces students’ strengths and strengthens their weaknesses.

Sight: Students see stimuli with their eyes. In class, this includes labels on classroom furniture and other items, word walls, anchor charts, or big books. For individual students, it could be flash cards or graphic organizers like Read It, Build It, Write It. With this tool, teachers would dictate or display a word, and students would build the word using letter tiles, and then students would write the word.

Hearing: Students hear stimuli with their ears. This can include hearing letters and letter sounds as you say them, singing rhyming songs, and participating in read-alouds. Shared reading is also a powerful tool for developing literacy. As you read or your students listen to an audiobook, they can interact with the text by underlining sight words or circling the long or short vowels that they hear.

Touch: Students touch stimuli with their hands. This is perhaps the biggest missing piece in our classrooms, but this hands-on approach is crucial for young learners. Students can manipulate letter tiles as they spell words and blend sounds. They can form letters or words with kinetic sand or play-dough, or they can simply trace sandpaper letters with their fingers as they say and hear letter names and sounds.

Air-writing and arm tapping both activate gross motor skills. When air-writing, have your students stand and air-write a word with their dominant arm, moving from their shoulder to promote large muscle movement. When arm-tapping, students tap their arm using their dominant hand from left to right, starting at their shoulder. Saying each sound of the word as they tap reinforces the sounds. Then, have students make a sweeping motion across their arm as they say the whole word, as if underlining it.

The three previously mentioned senses blend seamlessly into the concept of literacy. Smell and taste, however, are much harder to incorporate because they don’t return the same response as knowing letters by sight, sound, and touch/writing. In order for students to best learn the intended literacy skill, the following sensory activities are most effective when they are used with at least one other activity from the previous group.

Smell: Students smell stimuli with their noses. For example, students can form their letters in scented shaving cream or use smelly markers when tracing or writing—perhaps making the letter S with a marker that smells like sweet strawberries. Younger children can read a scratch-and-sniff book, or even make their own book using smelly stickers.

Taste: Students taste stimuli with their mouths. This is the most popular type of activity. You can give students their own portion of letter-shaped crackers, cookies, cereal, or pudding to spell words—they can write letters with their fingers or spell words on crackers using Cheez Whiz. And then, of course, they get to eat their creation.

The best part about multisensory activities is that they usually feel like play to children. But because of what we know about how the brain makes connections and stores memories, these strategies are powerful in helping our children learn how to read. Multisensory literacy activities provide necessary intervention for the students who need it, while making learning more fun for all of our students.

How Kids Fall In Love With Reading

Since the 1980’s there has been a double digit decline in the number of kids who say they read for pleasure. What accounts for this? A standardized test-driven shift towards textual analysis, where students increasingly are asked to dissect small and out-of-context segments of text, and where reading aloud and reading entire stories have fallen by the wayside. In Waldorf education, we take the opposite approach. We start with engaging the children’s imaginations through storytelling and reading aloud. We know that love of reading starts with a love of stories, and that a love of reading opens up a lifetime love of learning.

This article was originally published in The Atlantic in March, 2023

These days, when I explain to a fellow parent that I write novels for children in fifth through eighth grades, I am frequently treated to an apologetic confession: “My childdoesn’t read, at least not the way I did.” I know exactly how they feel—my tween and teen don’t read the way I did either. When I was in elementary school, I gobbled up everything: haunting classics such as The Witch of Blackbird Pond and gimmicky series such as the Choose Your Own Adventure books. By middle school, I was reading voluminous adult fiction like the works of Louisa May Alcott and J. R. R. Tolkien. Not every child is—or was—this kind of reader. But what parents today are picking up on is that a shrinking number of kids are reading widely and voraciously for fun.

These days, when I explain to a fellow parent that I write novels for children in fifth through eighth grades, I am frequently treated to an apologetic confession: “My childdoesn’t read, at least not the way I did.” I know exactly how they feel—my tween and teen don’t read the way I did either. When I was in elementary school, I gobbled up everything: haunting classics such as The Witch of Blackbird Pond and gimmicky series such as the Choose Your Own Adventure books. By middle school, I was reading voluminous adult fiction like the works of Louisa May Alcott and J. R. R. Tolkien. Not every child is—or was—this kind of reader. But what parents today are picking up on is that a shrinking number of kids are reading widely and voraciously for fun.

The ubiquity and allure of screens surely play a large part in this—most American children have smartphones by the age of 11—as does learning loss during the pandemic. But this isn’t the whole story. A survey just before the pandemic by the National Assessment of Educational Progress showed that the percentages of 9- and 13-year-olds who said they read daily for fun had dropped by double digits since 1984. I recently spoke with educators and librarians about this trend, and they gave many explanations, but one of the most compelling—and depressing—is rooted in how our education system teaches kids to relate to books.

What I remember most about reading in childhood was falling in love with characters and stories; I adored Judy Blume’s Margaret and Beverly Cleary’s Ralph S. Mouse. In New York, where I was in public elementary school in the early ’80s, we did have state assessments that tested reading level and comprehension, but the focus was on reading as many books as possible and engaging emotionally with them as a way to develop the requisite skills. Now the focus on reading analytically seems to be squashing that organic enjoyment. Critical reading is an important skill, especially for a generation bombarded with information, much of it unreliable or deceptive. But this hyperfocus on analysis comes at a steep price: The love of books and storytelling is being lost.

This disregard for story starts as early as elementary school. Take this requirement from the third-grade English-language-arts Common Core standard, used widely across the U.S.: “Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, distinguishing literal from nonliteral language.” There is a fun, easy way to introduce this concept: reading Peggy Parish’s classic, Amelia Bedelia, in which the eponymous maid follows commands such as “Draw the drapes when the sun comes in” by drawing a picture of the curtains. But here’s how one educator experienced in writing Common Core–aligned curricula proposes this be taught: First, teachers introduce the concepts of nonliteral and figurative language. Then, kids read a single paragraph from Amelia Bedelia and answer written questions.

For anyone who knows children, this is the opposite of engaging: The best way to present an abstract idea to kids is by hooking them on a story. “Nonliteral language” becomes a whole lot more interesting and comprehensible, especially to an 8-year-old, when they’ve gotten to laugh at Amelia’s antics first. The process of meeting a character and following them through a series of conflicts is the fun part of reading. Jumping into a paragraph in the middle of a book is about as appealing for most kids as cleaning their room.

But as several educators explained to me, the advent of accountability laws and policies, starting with No Child Left Behind in 2001, and accompanying high-stakes assessments based on standards, be they Common Core or similar state alternatives, has put enormous pressure on instructors to teach to these tests at the expense of best practices. Jennifer LaGarde, who has more than 20 years of experience as a public-school teacher and librarian, described how one such practice—the class read-aloud—invariably resulted in kids asking her for comparable titles. But read-alouds are now imperiled by the need to make sure that kids have mastered all the standards that await them in evaluation, an even more daunting task since the start of the pandemic. “There’s a whole generation of kids who associate reading with assessment now,” LaGarde said.

By middle school, not only is there even less time for activities such as class read-alouds, but instruction also continues to center heavily on passage analysis, said LaGarde, who taught that age group. A friend recently told me that her child’s middle-school teacher had introduced To Kill a Mockingbird to the class, explaining that they would read it over a number of months—and might not have time to finish it. “How can they not get to the end of To Kill a Mockingbird?” she wondered. I’m right there with her. You can’t teach kids to love reading if you don’t even prioritize making it to a book’s end. The reward comes from the emotional payoff of the story’s climax; kids miss out on this essential feeling if they don’t reach Atticus Finch’s powerful defense of Tom Robinson in the courtroom or never get to solve the mystery of Boo Radley.

Not every teacher has to focus on small chunks of literature at the expense of the whole plot, of course. But as a result of this widespread message, that reading a book means analyzing it within an inch of its life, the high/low dichotomy that has always existed in children’s literature (think The Giver versus the Goosebumps series) now feels even wider. “What do you call your purely fun books for kids?” a middle-grade author recently asked on Twitter. A retired fifth-grade teacher seemed flummoxed by the question: “I never called a book a fun book,” she wrote. “I’d say it’s a great book, a funny book, a touching book … So many books ARE fun!!”

And yet the idea that reading all kinds of books is enjoyable is not the one kids seem to be receiving. Even if most middle schoolers have read Diary of a Wimpy Kid, it’s not making them excited to move on to more challenging fare. Longer books, for example, are considered less “fun”; in addition, some librarians, teachers, and parents are noticing a decline in kids’ reading stamina after the disruption of the pandemic. You can see these factors at play in a recent call for shorter books. But one has to wonder whether this is also the not-entirely-unsurprising outcome of having kids interact with literature in paragraph-size bites.

We need to meet kids where they are; for the time being, I am writing stories that are shorter and less complex. At the same time, we need to get to the root of the problem, which is not about book lengths but the larger educational system. We can’t let tests control how teachers teach: Close reading may be easy to measure, but it’s not the way to get kids to fall in love with storytelling. Teachers need to be given the freedom to teach in developmentally appropriate ways, using books they know will excite and challenge kids. (Today, with more diverse titles and protagonists available than ever before, there’s also a major opportunity to spark joy in a wider range of readers.) Kids should be required to read more books, and instead of just analyzing passages, they should be encouraged to engage with these books the way they connect with “fun” series, video games, and TV shows.

Young people should experience the intrinsic pleasure of taking a narrative journey, making an emotional connection with a character (including ones different from themselves), and wondering what will happen next—then finding out. This is the spell that reading casts. And, like with any magician’s trick, picking a story apart and learning how it’s done before you have experienced its wonder risks destroying the magic.