Pushing Academics into Preschool Can Be Harmful

A comprehensive study finds significant drawbacks to pushing academics as early as in preschool. Researchers found that any initial academic gains were quickly erased, and children who attended academic-focused Pre-K were actually behind their peers in elementary and middle school. Another troubling finding was that students who experienced early academic pressure showed dramatic increases in behavioral issues later on. In Waldorf education, we focus on what is developmentally appropriate for each age group, understanding that preschool-age children especially need play, movement, and art, which are all critical to social-emotional health and future academic success.

This article was originally published by Anya Kamenetz on NPR.org

A top researcher says it's time to rethink our entire approach to preschool

Dale Farran has been studying early childhood education for half a century. Yet her most recent scientific publication has made her question everything she thought she knew.

"It really has required a lot of soul-searching, a lot of reading of the literature to try to think of what were plausible reasons that might account for this."

And by "this," she means the outcome of a study that lasted more than a decade. It included 2,990 low-income children in Tennessee who applied to free, public prekindergarten programs. Some were admitted by lottery, and the others were rejected, creating the closest thing you can get in the real world to a randomized, controlled trial — the gold standard in showing causality in science.

Farran and her co-authors at Vanderbilt University followed both groups of children all the way through sixth grade. At the end of their first year, the kids who went to pre-K scored higher on school readiness — as expected.

But after third grade, they were doing worse than the control group. And at the end of sixth grade, they were doing even worse. They had lower test scores, were more likely to be in special education, and were more likely to get into trouble in school, including serious trouble like suspensions.

"Whereas in third grade we saw negative effects on one of the three state achievement tests, in sixth grade we saw it on all three — math, science and reading," says Farran. "In third grade, where we had seen effects on one type of suspension, which is minor violations, by sixth grade we're seeing it on both types of suspensions, both major and minor."

That's right. A statewide public pre-K program, taught by licensed teachers, housed in public schools, had a measurable and statistically significant negative effect on the children in this study.

Farran hadn't expected it. She didn't like it. But her study design was unusually strong, so she couldn't easily explain it away.

"This is still the only randomized controlled trial of a statewide pre-K, and I know that people get upset about this and don't want it to be true."

Why it's a bad time for bad news

It's a bad time for early childhood advocates to get bad news about public pre-K. Federally funded universal prekindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds has been a cornerstone of President Biden's social agenda, and there are talks about resurrecting it from the stalled-out "Build Back Better" plan. Preschool has been expanding in recent years and is currently publicly funded to some extent in 46 states. About 7 in 10 4-year-olds now attend some kind of academic program.

This enthusiasm has rested in part on research going back to the 1970s. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman, among others, showed substantial long-term returns on investment for specially designed and carefully implemented programs.

To put it crudely, policymakers and experts have touted for decades now that if you give a 4-year-old who is growing up in poverty a good dose of story time and block play, they'll be more likely to grow up to become a high-earning, productive citizen.

What went wrong in Tennessee

No study is the last word. The research on pre-K continues to be mixed. In May 2021, a working paper (not yet peer reviewed) came out that looked at Boston's pre-K program. The study was a similar size to Farran's, used a similar quasi-experimental design based on random assignment, and also followed up with students for years. This study found that the preschool kids had better disciplinary records and were much more likely to graduate from high school, take the SATs and go to college, though their test scores didn't show a difference.

Farran believes that, with a citywide program, there's more opportunity for quality control than in her statewide study. Boston's program spent more per student, and it also was mixed-income, whereas Tennessee's program is for low-income kids only.

So what went wrong in Tennessee? Farran has some ideas — and they challenge almost everything about how we do school. How teachers are prepared, how programs are funded and where they are located. Even something as simple as where the bathrooms are.

In short, Farran is rethinking her own preconceptions, which are an entire field's preconceptions, about what constitutes quality pre-K.

Do kids in poverty deserve the same teaching as rich kids?

"One of the biases that I hadn't examined in myself is the idea that poor children need a different sort of preparation from children of higher-income families."

She's talking about drilling kids on basic skills. Worksheets for tracing letters and numbers. A teacher giving 10-minute lectures to a whole class of 25 kids who are expected to sit on their hands and listen, only five of whom may be paying any attention.

"Higher-income families are not choosing this kind of preparation," she explains. "And why would we assume that we need to train children of lower-income families earlier?"

Farran points out that families of means tend to choose play-based preschool programs with art, movement, music and nature. Children are asked open-ended questions, and they are listened to.

This is not what Farran is seeing in classrooms full of kids in poverty, where "teachers talk a lot, but they seldom listen to children." She thinks that part of the problem is that teachers in many states are certified for teaching students in prekindergarten through grade 5, or sometimes even pre-K-8. Very little of their training focuses on the youngest learners.

So another major bias that she's challenging is the idea that teacher certification equals quality. "There have been three very large studies, the latest one in 2018, which are not showing any relationship between quality and licensure."

Putting a bubble in your mouth

In 2016, Farran published a study based on her observations of publicly funded Tennessee pre-K classrooms similar to those included in this paper. She found then that the largest chunk of the day was spent in transition time. This means simply moving kids around the building.

Partly this is an architectural problem. Private preschools, even home-based day cares, tend to be laid out with little bodies in mind. There are bathrooms just off the classrooms. Children eat in, or very near, the classroom, too. And there is outdoor play space nearby with equipment suitable for short people.

Putting these same programs in public schools can make the whole day more inconvenient.

"So if you're in an older elementary school, the bathroom is going to be down the hall. You've got to take your children out, line them up and then they wait," Farran says. "And then, if you have to use the cafeteria, it's the same thing. You have to walk through the halls, you know: 'Don't touch your neighbor, don't touch the wall, put a bubble in your mouth because you have to be quiet.' "

One of Farran's most intriguing conjectures is that this need for control could explain the extra discipline problems seen later on in her most recent study.

"I think children are not learning internal control. And if anything, they're learning sort of an almost allergic reaction to the amount of external control that they're having, that they're having to experience in school."

In other words, regularly reprimanding kids for doing normal kid stuff at 4 years old, even suspending them, could backfire down the road as children experience school as a place of unreasonable expectations.

We know from other research that the control of children's bodies at school can have disparate racial impact. Other studies have suggested that Black children are disciplined more often in preschool, as they are in later grades. Farran's study, where 70% of the kids were white, found interactions between race, gender, and discipline problems, but no extra effect of attending preschool was detected.

Where to go from here

The United States has a child care crisis that COVID-19 both intensified and highlighted. Progressive policymakers and advocates have tried for years to expand public support for child care by "pushing it down" from the existing public school system, using the teachers and the buildings.

Farran praises the direction that New York City, for one, has taken instead: a "mixed-delivery" program with slots for 3- and 4-year-olds. Some kids attend free public preschool in existing nonprofit day care centers, some in Head Start programs and some in traditional schools.

But the biggest lesson Farran has drawn from her research is that we've simply asked too much of pre-K, based on early results from what were essentially showcase pilot programs. "We tend to want a magic bullet," she says.

"Whoever thought that you could provide a 4-year-old from an impoverished family with 5 1/2 hours a day, nine months a year of preschool, and close the achievement gap, and send them to college at a higher rate?" she asks. "I mean, why? Why do we put so much pressure on our pre-K programs?"

We might actually get better results, she says, from simply letting little children play.

The Waldorf Approach to Reading

Could pushing kids to read too early be counterproductive? Studies have shown that academic demands on young children have increased significantly in the last few decades, with mixed results. Many children feel unnecessary stress in response to early academic pressure, with long-term negative effects. In the Waldorf approach, children build their foundation to reading and writing organically, learning letters and sounds through stories, songs, word games, and more. This low-stress, natural approach starts in preschool and is integrated into every subject, every day. Our story-first approach helps children feel excited, rather than pressured, to learn to read and write, and engages their natural curiosity and love of learning.

This article was originally published by Whitney Ballard on the Bored Teachers website.

Study Shows: Pushing Kids to Read Too Much, Too Early is Counterproductive

It’s no secret that there is a constant push to do MORE and be BETTER in education. It often feels like a never-ending competition. If your child performs well, you “should” push him or her to be better than their peers. Your school may perform well, but you “should” push for the best in the state. Your state may do well, but you “should” push to beat other regions. In terms of news, our country is “so far behind”. These not-so-subtle messages are pushing our students, teachers, and all other school personnel far beyond age-appropriate performance levels. It starts with reading. Exactly why are we pushing kids to read so early?

In fact, learning to read too early can actually be counterproductive. Studies show it can lead to a variety of problems including increased frustration, misdiagnosed disorders, and unnecessary time and money spent teaching kids skills they don’t even have the skillset to understand yet.

“Escalating Academic Demand in Kindergarten: Counterproductive Policies” is one study that exemplifies the reverse of pushing children to read before they are ready:

“Narrow emphasis on isolated reading and numeracy skills is detrimental even to the children who succeed and is especially harmful to children labeled as failures…academic demands in kindergarten and first grade are considerably higher today than 20 years ago and continue to escalate.”

While it may seem like our kids are being pushed to succeed, they are often pushed too hard. They eventually accept defeat because it becomes increasingly difficult for students to keep up with impossible standards. Once kids “fall behind” according to educational standards, it creates an “I’m not good enough” mentality. This often sticks with them through school. The early years are extremely important for building confidence and a positive attitude. Yet every year, we fill the early years with more requirements that are proven to be confidence-killers and negative reinforcements.

There are virtually zero studies that show proof that reading early actually helps kids succeed long-term.

From a secondary teacher’s perspective, I have never been able to tell which child learned to read first, or which child could recite their ABCs before they were 3 years old. I could, however, tell which students felt confident in his or her abilities. Likewise, I could tell which students struggled to believe in themselves and which students expected to fail. As a teacher, I worry that we are putting skills like reading above social skills and confidence-building.

I could, however, tell which students felt confident in his or her abilities. Likewise, I could tell which students struggled to believe in themselves and which students expected to fail. As a teacher, I worry that we are putting skills like reading above social skills and confidence-building.

The teacher part of me can see the long-term struggle, but the parent-of-young-kids part of me can see the current stress. It is extremely difficult not to buy into the hype—the kind that tells you your young children need every educational toy on the market. Society tells mamas (and daddies) that their children are falling behind in sneaky ways through the use of advertisements, social media, etc.

Parents are constantly seeing children praised for their outstanding achievements and are being asked to compare their own children with the ‘exception’, not the rule. Many kids WANT to accelerate the process and constantly learn MORE. That is perfectly fine. Many kids also want to take their sweet time. That is also perfectly fine.

No two kids are the same. And no two students are the same. No kid should be pushed too hard too early to do anything, including reading.

As a teacher, I am constantly reassuring parents that their children are on track, despite the constant “push” for more. And as a parent, I am constantly re-centering myself on the idea that our children are natural learners who learn more from the world around them at a young age. As a friend, I want to encourage you to research the lack of benefits of learning to read too early—and look to your child for cues on when he or she is actually ready.

What age is truly the right age to learn to read? It depends on the individual.

In the meantime, let’s focus on building confidence, fostering creativity, and allowing our young kids to learn in the ways that suit them best.

The Value of an Unhurried Childhood

A recent New York Times article highlighted the importance of giving children an unhurried childhood, without an overpacked schedule of extracurricular activities and excessive homework. The pressure on Gen Z to excel at a young age has led to decreased mental health and increasing struggles at school. Waldorf Education takes a balanced approach, with plenty of time for children to play and explore, while also providing a joyful and well-rounded education that instills essential life skills, sparks a lifelong love of learning, and prepares them for a successful future.

This article was written by Shalini Shankar and originally published on July 9, 2021 in the New York Times

A Packed Schedule Doesn’t Really ‘Enrich’ Your Child

When the extracurricular-industrial complex came to a grinding halt last spring, parents were left scrambling to fill vast hours of unscheduled time. Some activities moved to remote instruction but most were canceled, and keeping children engaged became the bane of parents’ existence. Understandably, screens became default child care for younger kids and social lifelines for older ones.

As American society reopens, going back to our children’s prepandemic activities looks like an enticing way to reintroduce upper-elementary through high-school-age kids to the outside world. For parents with economic means, it’s tempting to return to a full slate of language classes, sports, music lessons and other extracurriculars — a guilt-free plan to keep kids busy with “enriching” activities while we get our jobs done.

But I suggest pausing before filling up their calendars again. We should not simply return children to their hectic prepandemic schedules.

Certainly, some amount of extracurricular activity can offer a welcome break from screens and help children nurture interests. But for Generation Z, the over-scheduling of extracurricular activities has been bad for stress and mental health and even worse for widening racial gaps. Moreover, as I learned when I conducted anthropological research for my book “Beeline: What Spelling Bees Reveal About Generation Z’s New Path to Success,” it no longer consistently improves the prospects of the white middle-class kids for whom it was designed.

But what can parents do with our kids instead? The answer is simple, though not easy to carry out: We can teach them (and perhaps relearn ourselves) the value of unstructured time and greater civic participation.

But what can parents do with our kids instead? The answer is simple, though not easy to carry out: We can teach them (and perhaps relearn ourselves) the value of unstructured time and greater civic participation.

This does not mean we should quit our day jobs and devote ourselves instead to endless hours of building forts and playing games. Exposing children to sports, music, art, programming or dance certainly has benefits — including physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and fun — but there are also good reasons to give children time to be bored. Not least of these is it forces them to figure out a way to entertain themselves.

For many kids today, scheduled time and down time on their screens are the only states of being. Paradoxically, scheduled unstructured time could address this. Cooking, reading a book, art projects and neighborhood walks are unlikely to completely replace screens, but routinizing blocks of time for these self-sustaining activities each day or several times a week could introduce children and teenagers to new pleasures, and at the very least invite calmness.

Gen Z acutely feels the pressure to be accomplished at a younger age. As kids take on a wider range of challenging activities younger, a trend that began with millennials but has grown to steroidal levels, the criteria for standing out in the college admissions process have shot up accordingly. It’s no wonder kids are stressed out.

The Slacker Generation, an initially disparaging label that Gen Xers have reclaimed, did not have to build a childhood résumé brimming with skills, expertise and accolades to get into college. Now many of these former slackers are parents worried about whether their kids are doing enough to stay competitive in college admissions and the job market. Those who can afford it feel pressure to pad their kids’ résumés as much as they can. A 2019 survey found that more than a quarter of “sports parents” spent upward of $500 per month, with some spending over $1,000 and jeopardizing their retirement savings.

But it’s clear by now that all this expensive enrichment won’t ensure kids’ success. Despite middle- and upper-class millennials mortgaging their childhood to get into college and then toiling through early adulthood in unpaid internships, they are unable to acquire the levels of economic and social security still held by their baby boomer parents.

Perhaps that’s why Gen Z has shown astute awareness of the dangers of overwork, with some high-profile Zoomers demonstrating acts of radical self-preservation. The Gen Z tennis star Naomi Osaka, for example, recently chose to prioritize her well-being over her career’s demands when she dropped out of the French Open after officials fined her for declining to participate in its post-match news conferences. Gen Z seems to have accepted that no matter how much you love your job, your job won’t love you back. Their parents — Gen Xers and even older millennials — were late to this lesson, and if they learned it at all, it was often only when they hit a wall with burnout.

Of course, preparing children for college and the job market is not the only goal of parents shelling out for guitar lessons or robot-making labs. Parents are also eager to expose their children to different ways of using their minds and bodies in the hope that they’ll discover passions that could become vocations, or simply lifelong joys. One passion that’s worth trying to instill is civic participation.

Of course, preparing children for college and the job market is not the only goal of parents shelling out for guitar lessons or robot-making labs. Parents are also eager to expose their children to different ways of using their minds and bodies in the hope that they’ll discover passions that could become vocations, or simply lifelong joys. One passion that’s worth trying to instill is civic participation.

As parents, we can reinforce the importance of caring beyond one’s own success. Taking your kids to volunteer or to protest injustices they see in the world are good ways to show them what it looks like to give back and replenish. The human and nonhuman connections they will make at food pantries and animal shelters can help kids cultivate empathy — itself a valuable skill for navigating life — while offsetting the anxiety footprint caused by today’s inflated standards for success.

It might feel counterintuitive to deny your children the leg up in life that many extracurriculars promise, but it’s worth examining that impulse too. The pandemic has exacerbated existing socioeconomic disparities, especially along racial lines. With widening wealth gaps, there will be even fewer opportunities to prioritize extracurricular activities for low-income kids. Rethinking the value of a packed calendar offers a concrete opportunity to narrow the racial and economic gaps between privileged and underprivileged kids.

Replacing video games with nature walks might not make you the most popular parent. Your kids may complain a little (or a lot) about losing some of their organized fun, since boredom is a feeling they’ve rarely experienced. But they’ll figure it out.

A Balanced Education Promotes Resilience

Waldorf education is an intentionally balanced approach to teaching with the goal of graduating happy, healthy, and resilient young people. We interweave academics, artistic activities, movement and outdoor time in a way that reduces stress and enhances learning. We provide rhythm for each day, season and year, which builds confidence and ensures that students feel secure. Social-emotional learning and problem solving are integrated throughout our curriculum so children develop the skills they need to thrive. We are a community where students feel seen, recognized, and challenged to do their best work and be their best selves.

This post is based on the findings of Ann S. Masten and Andrew J. Barnes in their National Library of Medicine paper, Resilience in Children: Developmental Perspectives. Please refer to the full paper for all citations.

Evidence continues to accumulate on the short- and long-term risks to health and well-being posed by adverse life experiences in children, particularly when adversities are prolonged, cumulative, or occurring during sensitive periods in early neurobiological development. Recent national and global examples include the growing concern about the impact of disasters, war, poverty, pandemics, climate change, and associated displacement on the global well-being of children. This confluence of threats to the present and future health of children motivates us to look at resilience and the factors that can support its development.

Resilience in humans can be broadly defined as the capacity to adapt successfully to challenges that threaten the function, survival, or future development of the individual. Resilience is also a feature of complex adaptive systems, including human individuals, but also families, economies, ecosystems, and organizations. This definition can also be applied to systems within an individual, such as the human immune system.

One of the most important implications of this definition is the idea that the resilience of a developing child is not circumscribed within the body and mind of that child. The capacity of an individual to adapt to challenges depends on their connections to other people and systems external to them through relationships and other processes. This includes their school environment and the relationships and experiences that are part of it.

For an individual person, resilience reflects all the adaptive capacity available at a given time in a given context that can be drawn upon to respond to current or future challenges facing the individual, through many different processes and connections. Resilience is not a trait, although individual differences in personality or cognitive skills clearly contribute to adaptive capacity. Supportive relationships play an enormous role in resilience across the lifespan. Close attachment bonds with a teacher or other caregiver and effective parenting can protect a young child in multiple ways that are not located “in the child”.

Human individuals have so much capacity for adaptation to adversity in part because their resilience depends on many interacting systems that co-evolved in biological and cultural evolution, conferring adaptive advantages. Moreover, children are often protected by multiple “back-up” systems, particularly embedded in their relationships with other people in their homes and communities.

Dose matters. Many studies of resilience have shown that the severity of exposure either to one extremely traumatic event or in the sense of cumulative risk, makes a difference. At the same time, these studies also show variation among individuals at similar levels of risk, some of whom are manifesting positive adaptation and development consistent with the presence of considerable resilience. In effect, these adaptive individuals are doing better than might be expected. These individuals motivated questions about how to account for their success and provided important clues for resilience science pertaining to the ongoing search for answers to the question of what makes a difference.

The shortlist of common resilience factors for child development shows that school environment can play an important role in helping children develop resilience, in particular the relationship development, teacher looping, intentional community, developmentally appropriate approach, and rhythms and rituals of a Waldorf education.

- Caring family, sensitive caregiving (nurturing family members)

- Close relationships, emotional security, belonging (family cohesion, belonging)

- Skilled parenting (skilled family management)

- Agency, motivation to adapt (active coping, mastery)Problem-solving skills, planning, executive function skills (collaborative problem-solving, family flexibility)

- Self-regulation skills, emotion regulation (co-regulation, balancing family needs)

- Self-efficacy, positive view of the self or identity (positive views of family and family identity)

- Hope, faith, optimism (hope, faith, optimism, positive family outlook)

- Meaning-making, belief life has meaning (coherence, family purpose, collective meaning-making)

- Routines and rituals (family routines and rituals, family role organization)

- Engagement in a well-functioning school

- Connections with well-functioning communities

An Education Where Kids Feel ‘Seen’

One of the best scientific predictors for how a child turns out in terms of happiness, academic success, and meaningful relationships is whether adults in their life consistently show up for them. Waldorf teachers strive to see and recognize each of their students, greeting them each morning individually, and working with them over multiple years to build on their unique strengths and meet their individual challenges so they can thrive.

This article was originally published by Daniel J. Siegel MD + Tina Payne Bryson PhD at https://ideas.ted.com/every-kid-needs-to-feel-seen-here-are-2-ways-you-can-do-this/

One way to set up a child for success: Take some time every day to really see them for who they are, not for who you want them to be.

Psychiatrist Daniel J. Siegel and Social worker Tina Payne Bryson.

One of the very best scientific predictors for how any child turns out — in terms of happiness, academic success, leadership skills, and meaningful relationships — is whether at least one adult in their life consistently shows up for them. And showing up doesn’t take a lot of time or energy, according to psychiatrist Daniel J. Siegel and social worker Tina Payne Bryson. Instead, it just requires acting in ways that ensure a child feels the Four S’s: Safe, Seen, Soothed and Secure. In this excerpt from their new book, The Power of Showing Up, Siegel and Bryson share two strategies that can make a child feel seen.

How good are you at seeing your kids? We mean really seeing them for who they are — perceiving them, making sense of them, and responding to them in timely and effective ways. This is how your child comes to experience the emotional sensation not only of belonging and of feeling felt, but also of being known.

Science suggests, and experience supports, that when we show up for our kids and give them the opportunity to be seen, they can learn how to see themselves with clarity and honesty. When we know our kids in a direct and truthful way, they learn to know themselves that way, too. Seeing our kids means that we ourselves need to learn how to perceive, make sense, and respond to them from a place of presence, to be open to who they actually are and who they are becoming, not who we’d like them to be and not filtered through our own fears or desires.

Take a moment and fast forward, in your mind, to the future when your child, now an adult, looks back and talks about whether he felt seen by you. Maybe he’s talking to a spouse, friend or therapist, someone they’d be brutally honest with. Perhaps he’s holding a cup of coffee, saying, “My mom, she wasn’t perfect, but I always knew she loved me just as I was.” Or, “My dad was always in my corner, even when I got in trouble.”

Would he say something like that? Or would he talk about how his parents always wanted him to be something he wasn’t, didn’t take the time to understand him, or wanted him to act in ways that weren’t authentic in order to play a particular role in the family or come across a certain way?

One of the worst ways we fail to see our children is to ignore their feelings. With a toddler, that might mean telling him, as he cries after falling down, “Don’t cry. You’re not hurt.” Or, an older child might feel genuinely anxious about attending the first meeting of a dance class. It’s unlikely she will feel more at ease if you say, “Don’t worry about it — there’s no reason to be nervous.”

Yes, we want to reassure our kids, and to be there for them to let them know they’ll be okay. But that’s far different from denying what they’re feeling, and explicitly telling them not to trust their emotions.

So instead, we want to simply see them. Notice what they’re experiencing, then be there for them and with them. We might say something like, “You’re going to be okay” or “Lots of people feel nervous on the first day. I’ll be there until you feel comfortable.”

When they feel felt and seen, it can create a sense of belonging as your child feels authentically known by you. She will also derive a sense of being both a “me” who is seen and respected and part of a “we”– something bigger than her solo self but that doesn’t require a compromise or the loss of her sense of being a unique individual. This is how seeing your child sets the foundation for future relationships where they can be an individual who is also a part of a connection.

What’s more, the empathy we communicate will be much more likely to create calm within our child. As is so often the case, when we show love and support, it makes life better not only for our child but for us as parents as well.

Strategy #1 for helping kids feel seen: Let curiosity lead you to take a deeper dive

A practical first step to helping our kids feel seen is just observe them — take the time to look at their behavior, discard preconceived ideas, and consider what’s really going on with. But really seeing them often requires more than just paying attention to what’s readily visible. Just as with adults, it’s often the case with children that there’s more going on beneath the surface than they let on. As parents, part of our responsibility is to dive deeper.

This curiosity is key. It’s one of the most important tools that a caring parent can use. When your toddler plays the “let’s push the plate of spaghetti off the high chair” game, your initial response might be frustration. If you assume he’s trying to press your buttons, you’ll respond accordingly. But if you look at his face and notice how fascinated he is by the splatter on the floor and the wall, you might feel and respond differently.

Cognitive scientists Alison Gopnik, Andrew Meltzoff and Patricia Kuhl have written about “the scientist in the crib,” explaining that a large percentage of what babies and young children do is part of an instinctual drive to learn and explore. If you can take a moment, pause and ask yourself, “I wonder why he did that?” If you see him as a young researcher who is gathering data as he explores this world, you can at the very least respond to his actions with intentionality and patience, even as you clean up his experiment.

We encourage parents to chase the “why” behind kids’ behavior. By asking “Why is my child doing that?” rather than immediately labeling an action as “bad behavior,” we’re much more likely to respond to the action for what it is. Sometimes it really may be a behavior that should be addressed. We believe that children definitely need boundaries, and it’s our job to teach them what’s okay and what’s not. But other times a child’s action may come from a developmentally typical place, in which case it should be responded to as such.

The same goes for other behaviors. If your child is quiet when she meets an adult and resists speaking up, she may not be refusing to be well mannered; she may be feeling shy or anxious. Again, that doesn’t mean you don’t teach her social skills along the way or encourage her to learn to speak in situations that are uncomfortable. It just means you want to see her for where she is right now. What are the feelings behind the behavior? Chase the why and examine the cause of her reticence; then you can respond more intentionally and effectively.

Strategy #2 for helping kids feel seen: Make space and time to look and learn

Much about seeing our kids is simply paying attention during the day, but it’s also about generating opportunities that allow your kids to show you who they are. Nighttime can be a great time to do this. There’s something about the end of the day, when the home gets quiet and the body feels tired, when distractions drop away and defenses are down, that makes us more apt to talk about our thoughts and memories, our fears and desires. This goes for all of us, adults and kids.

What’s required is a bit of effort and planning in terms of the family schedule. Kids need an adequate amount of sleep — we can’t stress that enough — so ideally you’ll begin bedtime early enough to make time for your usual routine plus a few minutes of chat or quiet waiting time to allow your children to talk if they are inclined. They might share details of their day or ask questions that help you gain a fuller understanding of what’s going on in their worlds — actual or imaginary.

What’s required is a bit of effort and planning in terms of the family schedule. Kids need an adequate amount of sleep — we can’t stress that enough — so ideally you’ll begin bedtime early enough to make time for your usual routine plus a few minutes of chat or quiet waiting time to allow your children to talk if they are inclined. They might share details of their day or ask questions that help you gain a fuller understanding of what’s going on in their worlds — actual or imaginary.

We know what some of you are thinking: “I don’t have one of those kids who willingly shares what they’re thinking and feeling.” We get it. The answer to the “How was your day” question seems to inevitably lead to the dreaded “Fine.” Imagining a chat time added to your child’s bedtime routine may produce the unpleasant image of you and your child silently lying next to each other, both of you waiting for something important to be shared.

We understand this concern. Keep in mind that the idea isn’t that every evening you’ll hear some earth-shattering revelation or deep exchange. That’s not realistic between adults, much less with kids. What’s more, it’s not the goal. The ultimate aim is to be present to your children — to create space and time to get to know them better and to understand them at a deeper level so you can help them grow into the fullness of who they are.

If you have a child who doesn’t eagerly share their inner thoughts, then you may need to ask more specific questions or pose ethical dilemmas you can consider together. The more you see and know your child, the easier this will become. At times, of course, silence is okay too. Being quiet together, simply breathing, can be intimate and connecting. So don’t feel pressure to force conversation when it’s not the right time.

We know it can be confusing, trying to determine what to say when and whether to encourage conversation or let things be quiet. But one of the best ways to see your kids — and to help them feel seen — is to create the space and time that cultivate opportunities for that kind of vision to take place.

Learning is Multi-Sensory. Teaching Should Be Too.

Children learn in many different ways. That’s why it is so important for teachers to bring concepts through multiple senses. In Waldorf schools we teach science through stories as well as outdoors in nature and in the lab. We move, build, and even bake and eat our math. We teach literature through theater. We sing our history and languages. We teach this way so that our curriculum reaches more children, more deeply, in a way that they love and remember.

This article is an example of the ways the techniques and skills that have always been integral in Waldorf education are being recognized and incorporated into mainstream education.

How Multisensory Activities Enhance Reading Skills

Reading lessons can involve more than just our eyes and ears. Here’s how you can promote reading skills using all five senses.

This article was written by Laura DePriest and originally published on edutopia.org

As educators, we know what it is like to work with children who catch on quickly. The light bulb moments happen fairly easily for them, and they will likely progress despite what we do. We teach them their letter sounds and review flash cards a few times, and from then on those students know and apply them as they learn how to put those sounds together and read.

What can be done for children who are taught those same letter sounds, have seen those same flash cards countless times, and still can’t remember which letter makes which sound? Sometimes those children eventually catch on, but what if they don’t? Often, we assume those children aren’t as smart as the other children. But what if the issue is that their brains are wired in a particular way, and how they are taught needs to be adjusted instead of just repeating the same methods over and over again in the same way?

Recent research has shown that the brain can adapt and make new connections even into old age. Our brains are ever-changing as we take in new information and new experiences. When we discover that a child doesn’t respond to and recall information in the traditional ways, it is important to consider how the brain receives information. The brain is exposed to a stimulus (hearing a phone ring or tasting spaghetti), at which point it analyzes and evaluates the information. Our five senses (sight, touch, hearing, smell, and taste) send information to our brain, which is designed to recognize sensations, initiate behaviors, and store memories.

MULTISENSORY ACTIVITIES REINFORCE STRENGTHS AND IMPROVE WEAKNESSES

So, what does knowing how amazing our brains are mean for us as preschool and early elementary teachers? Well, we can consider very practical ways to incorporate multisensory activities into our literacy instruction. Multisensory activities benefit all students and can be implemented daily in our classrooms. However, the key is to use more than one sense at a time in order to cement the concept. A sight-based activity alone isn’t enough; pair visual learning activities with another type. When a lesson uses multiple senses at once, it reinforces students’ strengths and strengthens their weaknesses.

Sight: Students see stimuli with their eyes. In class, this includes labels on classroom furniture and other items, word walls, anchor charts, or big books. For individual students, it could be flash cards or graphic organizers like Read It, Build It, Write It. With this tool, teachers would dictate or display a word, and students would build the word using letter tiles, and then students would write the word.

Hearing: Students hear stimuli with their ears. This can include hearing letters and letter sounds as you say them, singing rhyming songs, and participating in read-alouds. Shared reading is also a powerful tool for developing literacy. As you read or your students listen to an audiobook, they can interact with the text by underlining sight words or circling the long or short vowels that they hear.

Touch: Students touch stimuli with their hands. This is perhaps the biggest missing piece in our classrooms, but this hands-on approach is crucial for young learners. Students can manipulate letter tiles as they spell words and blend sounds. They can form letters or words with kinetic sand or play-dough, or they can simply trace sandpaper letters with their fingers as they say and hear letter names and sounds.

Air-writing and arm tapping both activate gross motor skills. When air-writing, have your students stand and air-write a word with their dominant arm, moving from their shoulder to promote large muscle movement. When arm-tapping, students tap their arm using their dominant hand from left to right, starting at their shoulder. Saying each sound of the word as they tap reinforces the sounds. Then, have students make a sweeping motion across their arm as they say the whole word, as if underlining it.

The three previously mentioned senses blend seamlessly into the concept of literacy. Smell and taste, however, are much harder to incorporate because they don’t return the same response as knowing letters by sight, sound, and touch/writing. In order for students to best learn the intended literacy skill, the following sensory activities are most effective when they are used with at least one other activity from the previous group.

Smell: Students smell stimuli with their noses. For example, students can form their letters in scented shaving cream or use smelly markers when tracing or writing—perhaps making the letter S with a marker that smells like sweet strawberries. Younger children can read a scratch-and-sniff book, or even make their own book using smelly stickers.

Taste: Students taste stimuli with their mouths. This is the most popular type of activity. You can give students their own portion of letter-shaped crackers, cookies, cereal, or pudding to spell words—they can write letters with their fingers or spell words on crackers using Cheez Whiz. And then, of course, they get to eat their creation.

The best part about multisensory activities is that they usually feel like play to children. But because of what we know about how the brain makes connections and stores memories, these strategies are powerful in helping our children learn how to read. Multisensory literacy activities provide necessary intervention for the students who need it, while making learning more fun for all of our students.

Adaptability Quotient: Educating for an Uncertain Future

With increasingly rapid changes in the nature of work, employers are interested not just in intelligence and social skills, but in an employee’s adaptability quotient–their ability to adjust to new challenges with flexibility, curiosity, courage, resilience, and problem-solving skills. In Waldorf education, we deepen rigorous academics by integrating art, outdoor education, music, theater, practical work, movement and hands-on learning. The depth and breadth of the Waldorf curriculum challenges students and develops crucial capacities that will help them adapt and thrive throughout their lives.

.jpg/Surpassing_Stem(1)__600x450.jpg)

This article was originally published Seb Murray on BBC.com

As workplaces change, is it enough to be smart? Enter AQ, the capacity to adapt that may well determine your future career success.

Once, if you wanted to assess how well someone might do climbing the career ladder, you might have considered asking them to take an IQ test. For years, it was thought that the intelligence quotient (IQ) test – which measures memory, analytical thinking and mathematical ability – was one of the best ways to predict our future job prospects.

More recently, there has been increased attention on emotional intelligence (EQ), broadly characterized as a set of interpersonal, self-regulation and communication skills. EQ is now widely seen as a tool kit that plays an important role in helping us succeed in multiple aspects of life. Both IQ and EQ are considered important to our career success. But today, as technology redefines how we work, the skills we need to thrive in the job market are evolving too. Enter adaptability quotient, or AQ, a subjective set of qualities loosely defined as the ability to pivot and flourish in an environment of fast and frequent change.

More recently, there has been increased attention on emotional intelligence (EQ), broadly characterized as a set of interpersonal, self-regulation and communication skills. EQ is now widely seen as a tool kit that plays an important role in helping us succeed in multiple aspects of life. Both IQ and EQ are considered important to our career success. But today, as technology redefines how we work, the skills we need to thrive in the job market are evolving too. Enter adaptability quotient, or AQ, a subjective set of qualities loosely defined as the ability to pivot and flourish in an environment of fast and frequent change.

“IQ is the minimum you need to get a job, but AQ is how you will be successful over time,” says Natalie Fratto, a New York-based vice-president at Goldman Sachs who became interested in AQ when she was investing in tech start-ups. She has subsequently presented a popular TED talk on the subject. Fratto says AQ is not just the capacity to absorb new information, but the ability to work out what is relevant, to unlearn obsolete knowledge, overcome challenges, and to make a conscious effort to change. AQ involves flexibility, curiosity, courage, resilience and problem-solving skills too.

Amy Edmondson, a professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School, says it is the breakneck speed of workplace change that will make AQ more valuable than IQ. Technology has vastly changed how many jobs are done, and the disruption will continue – over the next three years, 120 million people in the world’s 12 largest economies may need to be reskilled because of automation, according to a 2019 IBM study.

Any roles that involve spotting patterns in data – lawyers reviewing legal documents or doctors making a patient diagnosis, for example – are easy to automate, says Dave Coplin, CEO of The Envisioners, a UK-based technology consultancy. This is because an algorithm can do these tasks faster and more accurately than a human, he says. To avoid obsolescence, workers doing these jobs need to develop new skills like creativity to solve new problems, empathy to communicate better and accountability, using human intuition to supplement insight from machines. “If an algo can do 30% of the tasks that I used to do, what can I do with that spare capacity? The winners are those who choose to do things that algos can’t.”

Edmondson says every profession will require adaptability and flexibility, from banking to the arts. Say you are an accountant. Your IQ gets you through the examinations to become qualified, then your EQ helps you connect with an interviewer, land a job and develop relationships with clients and colleagues. Then, when systems change or aspects of work are automated, you need AQ to accommodate this innovation and adapt to new ways of performing your role.

Edmondson says every profession will require adaptability and flexibility, from banking to the arts. Say you are an accountant. Your IQ gets you through the examinations to become qualified, then your EQ helps you connect with an interviewer, land a job and develop relationships with clients and colleagues. Then, when systems change or aspects of work are automated, you need AQ to accommodate this innovation and adapt to new ways of performing your role.

All three quotients are somewhat complementary, since they all help you to solve problems and therefore adapt, Edmondson says. An ideal candidate possesses all three, but not everyone does. “There are rigid geniuses,” she says. Having IQ, but no AQ would leave you struggling to embrace new ways of working using your existing skills – and low AQ makes it harder to acquire new ones.

AQ is now increasingly being sought at the hiring level. According to the IBM study, 5,670 executives globally rated behavioral skills as most critical for the workforce today, and chief among them was the “willingness to be flexible, agile and adaptable to change”. Will Gosling, Deloitte’s UK human capital consulting leader, says there’s no definitive method of measuring adaptability like an IQ test, but companies have woken up to AQ’s value and are changing their recruitment processes to help identify people who may be high in it.

Deloitte has started using immersive online simulations where job candidates are assessed on how well they adapt to potential workplace challenges; one assessment involves choosing how you would encourage reluctant colleagues to join a company triathlon team. Deloitte also looks to hire people who have shown they can perform in different functions, industries or geographies. “This proves they are agile and a fast learner,” Gosling says.

Fratto of Goldman Sachs, meanwhile, suggests three ways AQ might manifest in potential candidates: if they can picture possible versions of the future by asking “what if” questions, if they can unlearn information to challenge presumptions and if they enjoy exploration or seeking out new experiences.

She says this is not a definitive recipe for AQ, but recruiters should pose these kinds of questions to tease out evidence of AQ in candidates. In fact, she puts them to founders of start-ups seeking her investment.“Start-ups go through evolutions,” she explains. “It’s not like the founder has a written job description; they need some of a fluctuating list of 30 or 50 skills to be successful.”

One good thing about AQ is that – even if you can’t measure it – experts say you can work to develop it. Penny Locaso, the Australian founder ofBKindred, an education companythat helps people to become more adaptable, says some people have more curious or courageous personalities, which may explain why they are naturally better at adapting than others. “However, if one does not continue to surf the edge of their discomfort, the adaptability you are born with could decrease over time.”

She suggests three ways to boost your adaptability: first, limit distractions and learn to focus so you can determine what adaptations to make. Second, ask uncomfortable questions, like for a pay rise, to develop courage and normalize fear. Third, be curious about things that fascinate you by having more conversations rather than Googling the answer, something “which wires our brains to be lazy” and diminishes our ability to solve difficult challenges.

Otto Scharmer, a senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management who has written books on learning from the emerging future, suggests other methods. In a TED talk, he recommends remaining open to new possibilities, trying to see a situation through someone else’s eyes and reducing your ego so that you can feel comfortable with the unknown.

One thing we do know is that the workplaces of the future will operate differently. We may not all be comfortable with the pace of change – but we can prepare. As Edmondson says: “Learning to learn is mission critical. The ability to learn, change, grow, experiment will become far more important than subject expertise.”

Cooking Up An Outstanding Language Program

The language learning process at our school has a lot of parallels with the Slow Food Movement. Great ingredients, seasonal produce, love, and appropriate time to prepare and cook are all hallmarks of an outstanding dish. A similar, thoughtful, well-paced approach leads to similarly outstanding results when teaching a language.

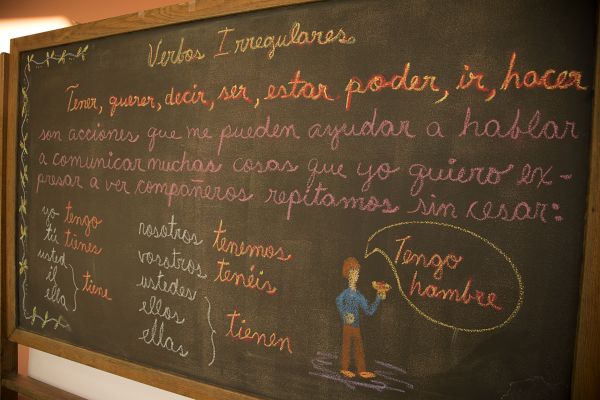

The aim of our World Languages program is to not only help students learn to communicate in a language other than English, but also to help them become familiar with and feel comfortable in a different culture and way of life. Rather than offering just a taste of the language, students are invited to a banquet of listening and speaking, songs and stories, art, recitations, movement and games. Classes are immersive and frequent, with four language lessons each week. In PreK-Grade 7, the students alternate between Spanish and German throughout the year, giving them a base in both languages and cultures. In Grades 8-12, students can choose which language they’d prefer to develop a stronger proficiency in and focus exclusively on that language. These are the ingredients that form the base of our language program.

Up to Grade 3, languages are taught entirely orally and auditorily, with reading and writing in Spanish and German introduced in Grade 4. Much like a child only hears and speaks their native language before learning to read and write it, allowing students the time for oral and auditory development of the languages before introducing reading and writing is a developmentally-appropriate approach to language learning. This “seasonal” approach helps to ensure students are prepared for and excited about the next level of learning.

Like the garnish that enhances the presentation of a dish, the beauty of the language is an important factor in our teaching. Through the inclusion of cultural experiences, history, music, and art, Spanish and German learning is enhanced. The teachers plan the subject matter in a way that invites children to open their hearts to the new language and fall in love with the culture as well as the words. This leads many students to pursue a first-hand taste of the culture and language in a native-speaking country through our high school exchange program.

Similar to crafting an amazing dish to share with those you love, our great teachers, eager students, and an age-appropriate, consistently-building approach is a recipe for creating a love of and respect for the languages and cultures that we are proud to share with our school community through our World Languages program.

If you are looking for the best game slots online in Southeast Asia, Rajawali888 or Rajawali888 it will be more interesting