Arts, Advocacy & Recognition by the Library of Congress

Working to rebuild community and identity in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

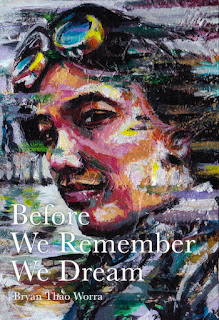

Bryan Thao Worra is a talented Laotian American writer, poet and community activist and has forged a path connecting experiences of refugees with the restorative aspects of writing. Born in Vientiane in the Kingdom of Laos, Bryan was adopted at three days old by an American pilot named John Worra, who flew for Royal Air Lao. He arrived in the U.S. six months later and eventually settled with his family in Saline, Michigan. He joined the Rudolf Steiner Lower School in it’s fledgling years (early 1980’s), when the school had mixed grades and only two classrooms. After graduating from 8th grade at RSSAA in 1987, he went on to Saline High School and eventually Otterbein College.

Bryan’s leadership in the writing community is being acknowledged during a livestreamed event at the Library of Congress on May 2 in recognition of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month. Appreciating his accomplishments, we reached out to him in order to learn a little about his thoughts on his Waldorf education and ideas around the arts and advocacy.

Your work over the last 20 years has focused on refugee resettlement and the arts. Can you tell us how you’ve connected with refugees through your writings and Southeast Asian diaspora?

The last two decades have taken me across the globe, searching for others who were scattered in the diaspora that followed the end of the Southeast Asian conflicts of the 20th century. I'd understood that many of the elders who were so fundamental to understanding how and why we are in America were passing away even as the younger generation didn't always know how to ask the questions they needed to preserve their family and community histories. In the United States, and in many parts of the world, those who don't understand their roots are often among the most easily exploited and many will find themselves adrift if they cannot understand who they have been, and how to express a future they see themselves in.

One aspect of my process has involved committing to a range of stories, poems, artworks and presentations on both the historical and the wildly imaginative, the cosmic and the everyday and to encourage my fellow refugees to consider different ways of expressing their own experiences and dreams. To give them the freedom to feel that it's ok to risk and to write more than one story, one poem, one idea to pass on to the next generation.

You joined RSSAA as a very young person. What do you remember about your experience with Waldorf education that has shaped your poetry and writing, or you as a person?

At first it was a startling experience, but a wonderful challenge engaging both my logical and creative sides. Our teachers there helped me find the confidence and initiative to direct my own learning and response to given lessons. One of the most important parts of that experience was creating my own textbooks. That absolutely impacted how I eventually made chapbooks and poetry collections later, and my enthusiasm for having experience on all sides of the publishing process. RSSAA prepared me for high school and college in such a way that I often felt way ahead of my peers and even a little out of place, enthusiastically seeking knowledge and ideas to share with others. It was always surprising to meet others who didn't have that energy and motivation. My years with RSSAA encouraged me to form lifelong friendships and to explore the deep connections between everything and to see my own experiences had a relationship to it all.

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

Growing up there weren't many books about my culture and my heritage in the encyclopedias or in popular culture. There was no clear timeline that helped me understand those essential questions: "Who am I? Where do I come from? Why am I here? Where are we going?" The arts provided a way to risk, and to experiment, to pose questions. They weren't legal depositions, but could often touch on great truths while I explored the questions of my identity and what it might mean to reconnect with others to rebuild our community after the war. Initially this was often a rather non-linear process but it became essential, much like the process in solving a jigsaw puzzle.

Do you have advice for young people who want to pair the arts with advocacy?

There are many ways to articulate a vision for a better world. Sometimes by showing a new model of possibilities, sometimes through warnings of unintended or even intended consequences. Each technique has its uses and limitations, and an artist will always face a particular risk with advocacy: Do we reinforce the existing arguments or dismantle them for something better? Pushback is possible with both. We have to commit to learning as much as we can on a given issue, and then we have to give ourselves permission to risk a new way of expressing what matters to us. And sometimes, an artist must find ways to avoid the inertia that comes from waiting for "the perfect" and instead seek "the good" and "the necessary" at a given point of time. As you get started, the key thing to remember is that you don't need to be the last word, but a word that gets the conversations started to create change.

The “Memory, Experience & Imagination in Works of Lao & Hmong American Authors” event will be livestreamed on Monday, May 2 at 6:30 pm EDT. It will be available for viewing afterward in the Library's Events Videos collection.

More Than a Body: Capturing the Essence of Another Human

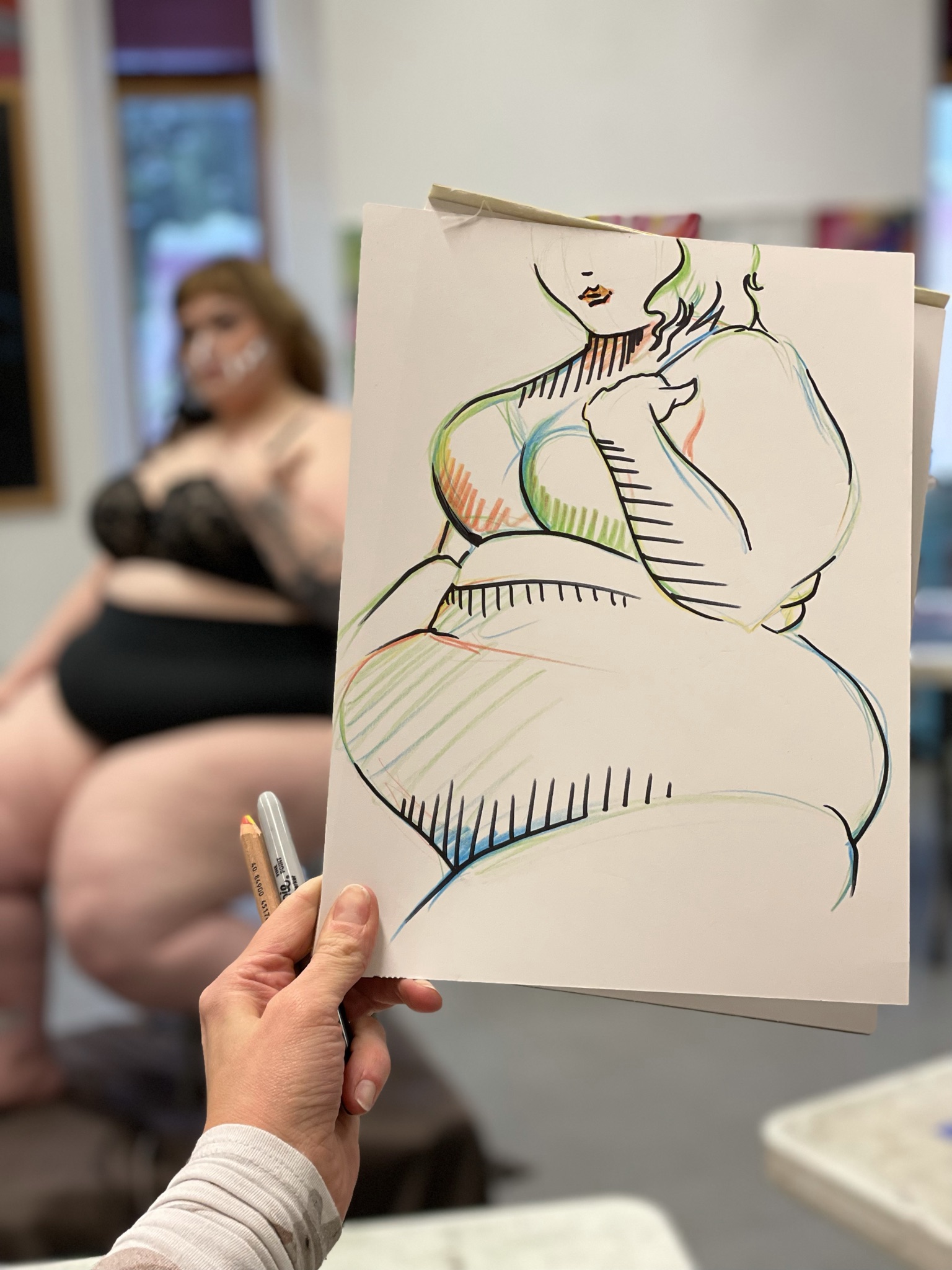

When Elizaveta McFall (HS Art faculty, parent & HS Alum ‘04) began teaching the HS figure-drawing class over four years ago, she

Elizaveta saw an opportunity to re-imagine the approach to this tradition by establishing a dialogue and relationship with the models themselves. She wanted her students to fall in love with people and to see them as art. From her perspective, it is easy to learn the proportions of the human body, but the real work is to capture the model as they are.

She wanted her students to fall in love with people and to see them as art.

In the past, only one model would visit the classroom over a period of several weeks. Now there was an opportunity to open that experience up by inviting multiple models to pose on different days, giving the students a chance to see a variety of human bodies. Her models have evolved from “accepted” male and female body-types to now include a variety of bodies, sizes, gender, and age. This year, she invited a professional wheelchair basketball player who entered the class on his prosthetic legs, talked with the class, then removed his legs and posed for the students in his athletic wheelchair.

Elizaveta wanted to integrate social-emotional learning into the students experience by establishing a relationship with the models during their session. She creates an environment for the models and students to have a conversation. Before the model visits, the students talk about how the model might feel when they arrive - vulnerable, uncomfortable, or nervous. She asks students how do we make them comfortable? Should we giggle (even if it’s not about the model)? Should we ask questions and what kinds of questions? She prepares them to think about “nude” as a genre in art and to look at the model as nude - not naked. Students work through how those terms make them feel.

Before the model visits, the students talk about how the model might feel when they arrive - vulnerable, uncomfortable, or nervous.

Through earlier conversations with the models, Elizaveta learns about their lives, hobbies, jobs or interests. She asks them to think about the shape of their bodies and learns what they are comfortable talking about. This information is then integrated into her class, so she can model the conversation for students, who then begin to pick-up on her approach.

Once the model is back in the room, a comfortable rapport builds as Elizaveta demonstrates for students the questions to ask the models. Nikki, a plus-sized model, is asked about her journey of loving her curvy body. Elizaveta asks the students, “Does Nikki want large paper or small? Do we use straight lines or curved? Where is she most narrow or where is she most broad? What ways can we capture Nikki’s curves?”. It becomes clear that their bodies are aspects of who they are. A trans male model is not introduced by this title but through Elizaveta’s questions, they reveal a favorite part of their transformed body. The conversation with Zeus, a professional wheelchair athlete, reveals how he functions in the sport and how he uses his prosthetics to walk. A pregnant model talks about the temporary body she wears, where she gained weight and the purpose of those changes for the baby.

For students, seeing a body like their own or talking with a trans person or someone with a disability who have fully fallen in love with themselves can be a very powerful experience. Student interests are diverse - from the hard sciences, computers, history, or fine arts - but every high school senior participates in the figure drawing class and is given the opportunity to appreciate the beauty in the diversity of human bodies and interact with the amazing people who inhabit them. Elizaveta knew this new approach would be a unique experience, and the greater impact it would have on our students social-emotional skills and opportunities for growth beyond artistic abilities.

For students, seeing a body like their own or talking with a trans person or someone with a disability who have fully fallen in love with themselves can be a very powerful experience.