Cooking Up An Outstanding Language Program

The language learning process at our school has a lot of parallels with the Slow Food Movement. Great ingredients, seasonal produce, love, and appropriate time to prepare and cook are all hallmarks of an outstanding dish. A similar, thoughtful, well-paced approach leads to similarly outstanding results when teaching a language.

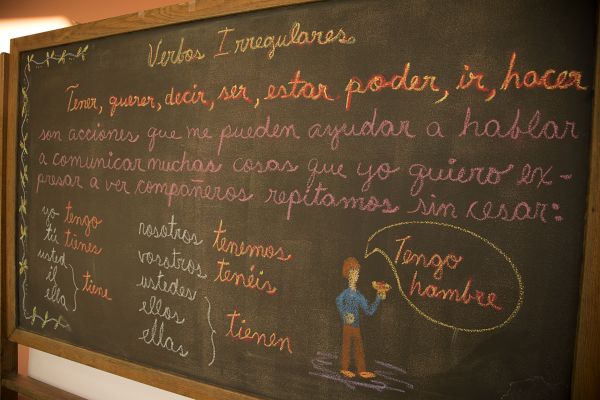

The aim of our World Languages program is to not only help students learn to communicate in a language other than English, but also to help them become familiar with and feel comfortable in a different culture and way of life. Rather than offering just a taste of the language, students are invited to a banquet of listening and speaking, songs and stories, art, recitations, movement and games. Classes are immersive and frequent, with four language lessons each week. In PreK-Grade 7, the students alternate between Spanish and German throughout the year, giving them a base in both languages and cultures. In Grades 8-12, students can choose which language they’d prefer to develop a stronger proficiency in and focus exclusively on that language. These are the ingredients that form the base of our language program.

Up to Grade 3, languages are taught entirely orally and auditorily, with reading and writing in Spanish and German introduced in Grade 4. Much like a child only hears and speaks their native language before learning to read and write it, allowing students the time for oral and auditory development of the languages before introducing reading and writing is a developmentally-appropriate approach to language learning. This “seasonal” approach helps to ensure students are prepared for and excited about the next level of learning.

Like the garnish that enhances the presentation of a dish, the beauty of the language is an important factor in our teaching. Through the inclusion of cultural experiences, history, music, and art, Spanish and German learning is enhanced. The teachers plan the subject matter in a way that invites children to open their hearts to the new language and fall in love with the culture as well as the words. This leads many students to pursue a first-hand taste of the culture and language in a native-speaking country through our high school exchange program.

Similar to crafting an amazing dish to share with those you love, our great teachers, eager students, and an age-appropriate, consistently-building approach is a recipe for creating a love of and respect for the languages and cultures that we are proud to share with our school community through our World Languages program.

Is Travel Good For Teens?

Is it safe? Will they make good choices? What if something happens? Will they meet nice people?

These are just a few of the questions that might pop up when considering allowing your teen to travel - and they're all valid and worthy of discussion. But a question that might be even more important is, what will they learn? For parents, the educational aspect of travel is most likely the biggest reason why they send their kids on an overseas educational program with their school, like our senior trip to Italy. But what about travel with non-school groups - or even solo travel - for teens?

Traveling is the moment when the textbook comes alive, when everyday objects look completely different and when common greetings sound exotic. For teens, traveling abroad is exhilarating, stimulating, frustrating and—whether they're looking for it or not—extremely educational. Experts say that the educational benefit for teens goes far beyond learning historical facts, architectural styles, conversational phrases and even a working knowledge of a foreign subway system. Travel is an excellent way for students to develop the vital skills like critical thinking and problem solving that will enable them to compete in an increasingly globally interdependent economy.

“I think the biggest thing travel does for teens is to help them to see beyond their own somewhat limited world and to see how other people live,” says Christine Schelhas-Miller, who taught adolescent development at Cornell University for many years and is the co-author of Don’t Tell Me What to Do, Just Send Money: The Essential Parenting Guide to the College Years.

Travel is particularly good for developing critical thinking as it forces teens to examine their own values and beliefs from the perspective of a different culture. They become aware of aspects of their lives that they have taken for granted and never examined. - Christine Schelhas-Miller

Improvement in critical-thinking skills can translate into big gains in the classroom. Travel can help students develop all of what educators call the 4 Cs (critical thinking and problem solving, communication, collaboration, and creativity and innovation), says Dr. Jessie Voigts, who has a PhD in international education and runs wanderingeducators.com, a global community of educators sharing travel experiences.

“Travel encourages critical thinking (especially when comparing intercultural differences), problem solving (in so many ways—money, transportation, food, events, cultures, languages, etc.) and communication (both verbal and non-verbal, which is key to any communication event, globally),” says Voigts, author of Bringing the World Home: A Resource Guide to Raising Intercultural Kids. "It also encourages collaboration (working together with your travel partners or locals to fulfill your basic needs), creativity (finding a creative solution to a travel problem) and innovation (whether it’s a way to hold your luggage together with whatever is on hand or finding a new route in an unfamiliar town past a parade to get where you need to go).” And, through these experiences, teens are becoming more flexible and adaptable along the way, two more skills that are essential in the 21st Century’s virtual workplace.

Our kids face an entirely different world than that of their parents and grandparents. They need more than school and college to get a job. They need to learn flexibility, adaptability, and other skills to succeed in today’s global economy. Our coworkers and neighbors are no longer just next door, but all around the world.

Traveling—not just being a tourist, but smart travel—helps teens learn flexibility and adaptability, and creates an open-minded worldview that allows teens to work well with others anywhere in the world.” - Dr. Jessie Voigts

It may take teens—and their parents—some time to realize that they have gained all of these skills from their travels abroad. But it probably won’t take anyone long to figure out that these teens have learned a lot about something very close to home: themselves. Unexpected events always happen to travelers and, when faced with these events without an adult to guide them, teens develop problem-solving skills and confidence in their abilities to manage their lives. When teens travel, they expect to learn so much about the other country, but may also make some important self-discoveries along the way.

Some Life Benefits of Traveling as a Teenager:

- Learn How to Save and Budget Money - Sure, learning about money starts at a young age, but there is real-life experience and deferred gratification in saving up all school year for an extended trip that a teen can proudly say that they paid for. Plus there's the skill of budgeting throughout the trip.

- Ability to Make an Itinerary - Itineraries are just as dynamic as the places visited and this will reflect upon your teens travels no matter where they venture. They'll build flexibility when they need to make and change their itinerary so they can have the best experience possible.

- Build Problem-solving Skills - World travel wouldn’t be complete without the occasional bump in the road. Dealing with problems like pouring rain when the forecast predicted sun or a broken suitcase zipper will make them a savvy problem-solver as they work through predicaments proactively and positively rather than allowing them to spoil the trip.

- Become an Independent and Responsible Young Person - When traveling around with family and friends, it’s super easy to follow their lead and let others take care of things like tickets, transportation, meals, itineraries, etc. – The list goes on and on. Traveling without the familiarity of people from home means your teen will need to take more responsibility for their own actions, as well as look out for those they are with. This means showing up prepared, making the effort to participate, and being accountable throughout the trip.

- Break Stereotypes and Experience New Cultures - Unfortunately, people are often quick to believe stereotypes about other countries and their cultures, especially the negative ones. This is true of Americans' views of overseas destinations, as well as other countries negative perceptions of Americans. When traveling, your teen will have the opportunity to break this cycle by keeping an open mind and an open heart and sharing everything that it means to be a global citizen.

While every family and every teen is unique, when it comes to travel it's possible the pros outweigh any cons. Traveling teaches meaningful life skills, provides an opportunity to meet new people, facilitates cultural appreciation, and teaches the ability to adapt to new environments. Travel is a fantastic way of gaining these unique experiences which develop youth into more well-rounded citizens, all while having fun along the way!

International High School Students Find a Community at RSSAA

Motivated students and families from around the world look for immersive experiences at American high schools where they can learn English, absorb American culture, and prepare for post-secondary education at English-speaking institutions. As the Waldorf movement continues to grow around the world, some international parents are looking for a Waldorf high school experience when their own country doesn’t have a program established. At the same time, there are international families who have never known about Waldorf education, but appreciate the liberal arts curriculum, community feeling, and host-family experience the Rudolf Steiner High School offers. Over the past 18 years, 75 international students have found their way to Steiner High school and have emerged with skills and relationships that have prepared them for their next steps in life.

Motivated students and families from around the world look for immersive experiences at American high schools where they can learn English, absorb American culture, and prepare for post-secondary education at English-speaking institutions. As the Waldorf movement continues to grow around the world, some international parents are looking for a Waldorf high school experience when their own country doesn’t have a program established. At the same time, there are international families who have never known about Waldorf education, but appreciate the liberal arts curriculum, community feeling, and host-family experience the Rudolf Steiner High School offers. Over the past 18 years, 75 international students have found their way to Steiner High school and have emerged with skills and relationships that have prepared them for their next steps in life.

Mary Zeng (’21) deeply appreciates her experience here. What was important to her, and her family, was to find a school that assisted her learning English along with broad academic coursework. Thanks to our smaller classes, she was able to form supportive relationships with her teachers that continue today. Her immersion in American culture with a Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor high school family both dramatically increased her acquisition of English and gave her a caring environment to navigate her high school years. She sees the relationships she built with classmates, her host family, and the wider Ann Arbor community, as her home-base in America as she attends University of Massachusetts - Amherst.

When Vivian Wang’s (’17) parents were trying to find an American high school for her to attend, they were looking for a good experience both with an English-speaking family - so she could learn the language and culture - and an academic setting that appreciated both the sciences and the arts. Vivian’s host family had a 1-year-old child and they loved getting to know Vivian and  helping her study for classes and learn English. She continues to stay in touch with them and they even helped her move to Atlanta to attend Georgia Tech. Vivian also appreciated the strong relationships she had with her teachers, where she was encouraged to ask questions and be proactive in her learning.

helping her study for classes and learn English. She continues to stay in touch with them and they even helped her move to Atlanta to attend Georgia Tech. Vivian also appreciated the strong relationships she had with her teachers, where she was encouraged to ask questions and be proactive in her learning.

For Irene Zhang (’21), two of the reasons she came to RSSAA were to continue studying at a place that was more artistically oriented, and finding a home-life experience in a city that was safe. In Ann Arbor, she lived with a Chinese-American family who had small children and she had a marvelous experience. She became a part of their family, and they treasured the opportunity to learn from her. She looks forward to visiting them during breaks from her studies at Tufts University.

The host-family experience is just as rewarding as the educational. For many, the international student becomes a part of the family, participating in their customs, meals, and celebrations. Irene’s host mother, Bing Li, found the hosting experience wonderful for her family with two young children. During the pandemic, they got to spend even more time with Irene and she truly became part of their family. High school families enjoy a peer-to-peer experience that can enhance the high school years for their own student as well as their guest student. Some past host families are looking forward to hosting another international student when the opportunity arises.

The city of Ann Arbor is attractive to many international students because of its safety, a large international community (especially for Asian students) and being within the vicinity of the University of Michigan. For a teenager, Ann Arbor provided  outlets beyond school to connect with others. Mary took tennis lessons at a local club and explored the various teen locales in the region. Irene attended UM football games with friends and immersed herself in artistic experiences. Learning soccer was exciting for Vivian, and she found the coach very helpful and her teammates welcoming. Students also can participate in a variety of after-school clubs, like Model United Nations, that connect them in new ways to their American classmates.

outlets beyond school to connect with others. Mary took tennis lessons at a local club and explored the various teen locales in the region. Irene attended UM football games with friends and immersed herself in artistic experiences. Learning soccer was exciting for Vivian, and she found the coach very helpful and her teammates welcoming. Students also can participate in a variety of after-school clubs, like Model United Nations, that connect them in new ways to their American classmates.

International students at RSSAA also form bonds with each other as they take English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, led by skilled ESL teachers who become a reliable support-system to complete their academic coursework. For some students, these teachers become a sounding-board for other questions or concerns they have during the school year.

Our international students have found a well-balanced program at RSSAA that brings the warmth of a family experience while undertaking an American high school education. For international students and host families alike, an impactful, life-changing experience can happen, and relationships are created that can continue years after graduation!

If you're interested in learning more about how you can help create an amazing experience for an international student, please reach out to Sian Owen-Cruise at sowen-cruise@steinerschool.org.

Arts, Advocacy & Recognition by the Library of Congress

Working to rebuild community and identity in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

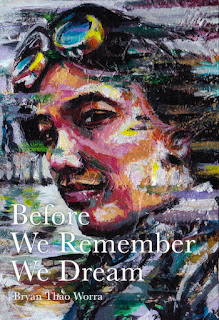

Bryan Thao Worra is a talented Laotian American writer, poet and community activist and has forged a path connecting experiences of refugees with the restorative aspects of writing. Born in Vientiane in the Kingdom of Laos, Bryan was adopted at three days old by an American pilot named John Worra, who flew for Royal Air Lao. He arrived in the U.S. six months later and eventually settled with his family in Saline, Michigan. He joined the Rudolf Steiner Lower School in it’s fledgling years (early 1980’s), when the school had mixed grades and only two classrooms. After graduating from 8th grade at RSSAA in 1987, he went on to Saline High School and eventually Otterbein College.

Bryan’s leadership in the writing community is being acknowledged during a livestreamed event at the Library of Congress on May 2 in recognition of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month. Appreciating his accomplishments, we reached out to him in order to learn a little about his thoughts on his Waldorf education and ideas around the arts and advocacy.

Your work over the last 20 years has focused on refugee resettlement and the arts. Can you tell us how you’ve connected with refugees through your writings and Southeast Asian diaspora?

The last two decades have taken me across the globe, searching for others who were scattered in the diaspora that followed the end of the Southeast Asian conflicts of the 20th century. I'd understood that many of the elders who were so fundamental to understanding how and why we are in America were passing away even as the younger generation didn't always know how to ask the questions they needed to preserve their family and community histories. In the United States, and in many parts of the world, those who don't understand their roots are often among the most easily exploited and many will find themselves adrift if they cannot understand who they have been, and how to express a future they see themselves in.

One aspect of my process has involved committing to a range of stories, poems, artworks and presentations on both the historical and the wildly imaginative, the cosmic and the everyday and to encourage my fellow refugees to consider different ways of expressing their own experiences and dreams. To give them the freedom to feel that it's ok to risk and to write more than one story, one poem, one idea to pass on to the next generation.

You joined RSSAA as a very young person. What do you remember about your experience with Waldorf education that has shaped your poetry and writing, or you as a person?

At first it was a startling experience, but a wonderful challenge engaging both my logical and creative sides. Our teachers there helped me find the confidence and initiative to direct my own learning and response to given lessons. One of the most important parts of that experience was creating my own textbooks. That absolutely impacted how I eventually made chapbooks and poetry collections later, and my enthusiasm for having experience on all sides of the publishing process. RSSAA prepared me for high school and college in such a way that I often felt way ahead of my peers and even a little out of place, enthusiastically seeking knowledge and ideas to share with others. It was always surprising to meet others who didn't have that energy and motivation. My years with RSSAA encouraged me to form lifelong friendships and to explore the deep connections between everything and to see my own experiences had a relationship to it all.

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

What role did the arts play for you as you grew up?

Growing up there weren't many books about my culture and my heritage in the encyclopedias or in popular culture. There was no clear timeline that helped me understand those essential questions: "Who am I? Where do I come from? Why am I here? Where are we going?" The arts provided a way to risk, and to experiment, to pose questions. They weren't legal depositions, but could often touch on great truths while I explored the questions of my identity and what it might mean to reconnect with others to rebuild our community after the war. Initially this was often a rather non-linear process but it became essential, much like the process in solving a jigsaw puzzle.

Do you have advice for young people who want to pair the arts with advocacy?

There are many ways to articulate a vision for a better world. Sometimes by showing a new model of possibilities, sometimes through warnings of unintended or even intended consequences. Each technique has its uses and limitations, and an artist will always face a particular risk with advocacy: Do we reinforce the existing arguments or dismantle them for something better? Pushback is possible with both. We have to commit to learning as much as we can on a given issue, and then we have to give ourselves permission to risk a new way of expressing what matters to us. And sometimes, an artist must find ways to avoid the inertia that comes from waiting for "the perfect" and instead seek "the good" and "the necessary" at a given point of time. As you get started, the key thing to remember is that you don't need to be the last word, but a word that gets the conversations started to create change.

The “Memory, Experience & Imagination in Works of Lao & Hmong American Authors” event will be livestreamed on Monday, May 2 at 6:30 pm EDT. It will be available for viewing afterward in the Library's Events Videos collection.

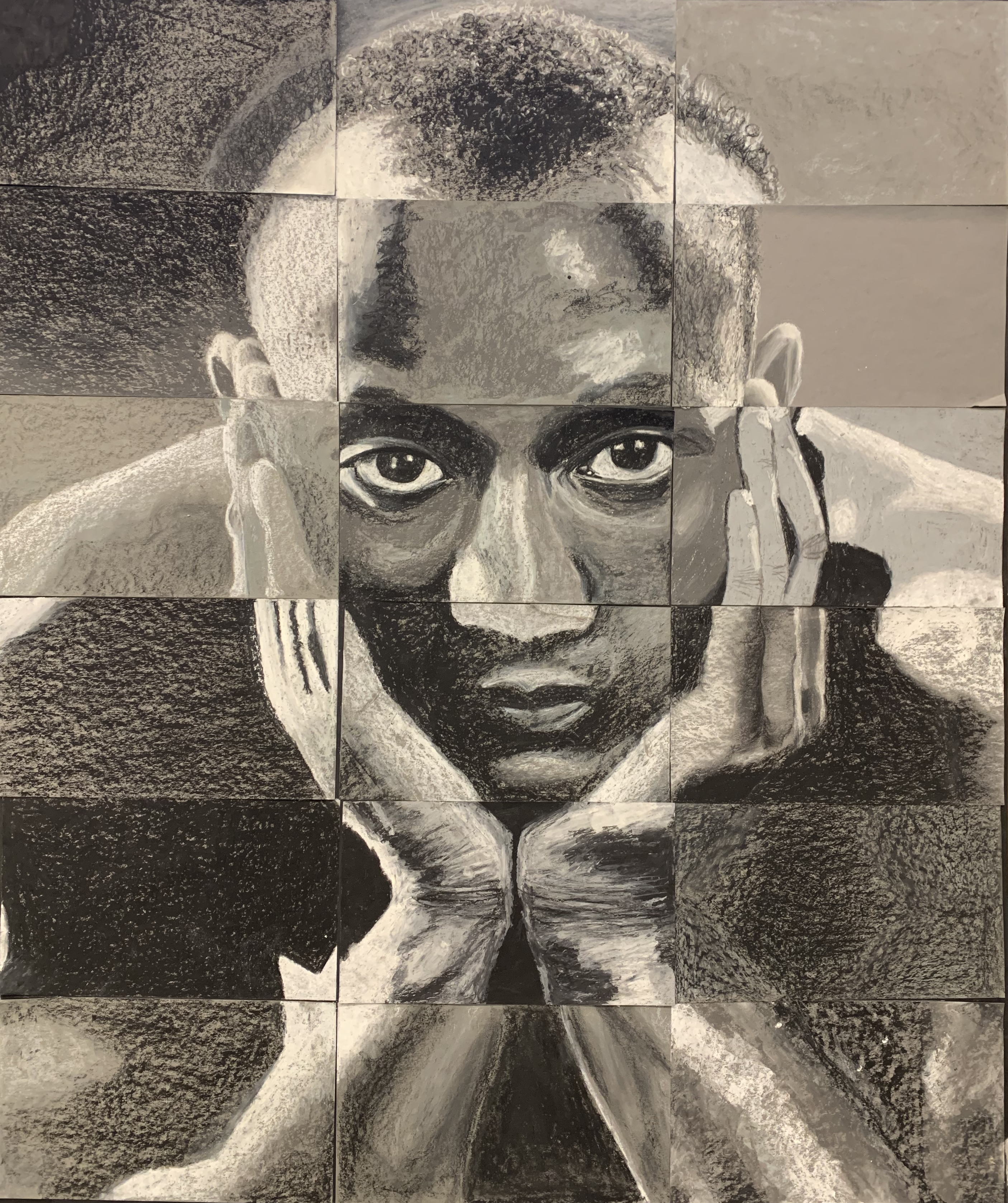

More Than a Body: Capturing the Essence of Another Human

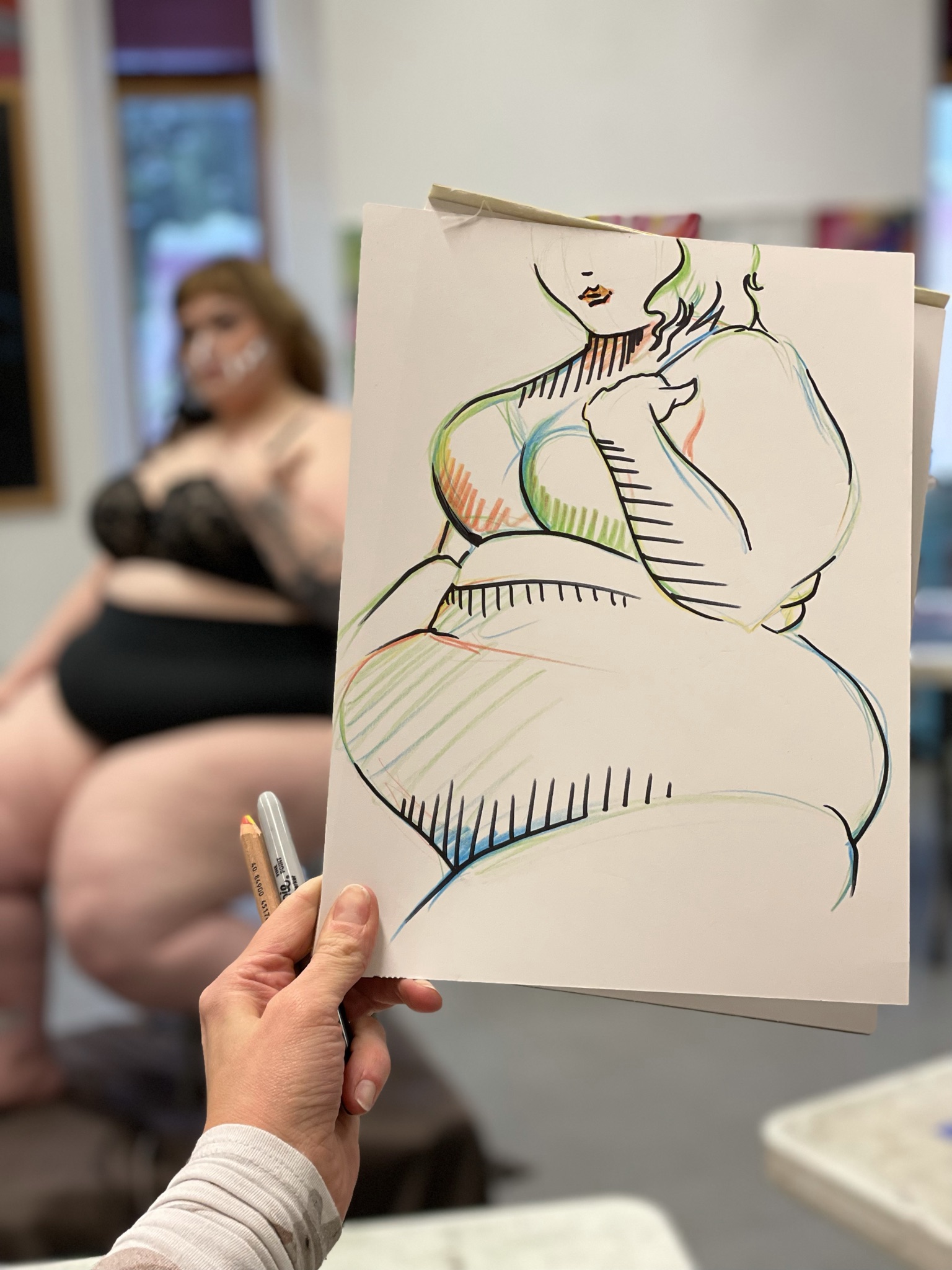

When Elizaveta McFall (HS Art faculty, parent & HS Alum ‘04) began teaching the HS figure-drawing class over four years ago, she

Elizaveta saw an opportunity to re-imagine the approach to this tradition by establishing a dialogue and relationship with the models themselves. She wanted her students to fall in love with people and to see them as art. From her perspective, it is easy to learn the proportions of the human body, but the real work is to capture the model as they are.

She wanted her students to fall in love with people and to see them as art.

In the past, only one model would visit the classroom over a period of several weeks. Now there was an opportunity to open that experience up by inviting multiple models to pose on different days, giving the students a chance to see a variety of human bodies. Her models have evolved from “accepted” male and female body-types to now include a variety of bodies, sizes, gender, and age. This year, she invited a professional wheelchair basketball player who entered the class on his prosthetic legs, talked with the class, then removed his legs and posed for the students in his athletic wheelchair.

Elizaveta wanted to integrate social-emotional learning into the students experience by establishing a relationship with the models during their session. She creates an environment for the models and students to have a conversation. Before the model visits, the students talk about how the model might feel when they arrive - vulnerable, uncomfortable, or nervous. She asks students how do we make them comfortable? Should we giggle (even if it’s not about the model)? Should we ask questions and what kinds of questions? She prepares them to think about “nude” as a genre in art and to look at the model as nude - not naked. Students work through how those terms make them feel.

Before the model visits, the students talk about how the model might feel when they arrive - vulnerable, uncomfortable, or nervous.

Through earlier conversations with the models, Elizaveta learns about their lives, hobbies, jobs or interests. She asks them to think about the shape of their bodies and learns what they are comfortable talking about. This information is then integrated into her class, so she can model the conversation for students, who then begin to pick-up on her approach.

Once the model is back in the room, a comfortable rapport builds as Elizaveta demonstrates for students the questions to ask the models. Nikki, a plus-sized model, is asked about her journey of loving her curvy body. Elizaveta asks the students, “Does Nikki want large paper or small? Do we use straight lines or curved? Where is she most narrow or where is she most broad? What ways can we capture Nikki’s curves?”. It becomes clear that their bodies are aspects of who they are. A trans male model is not introduced by this title but through Elizaveta’s questions, they reveal a favorite part of their transformed body. The conversation with Zeus, a professional wheelchair athlete, reveals how he functions in the sport and how he uses his prosthetics to walk. A pregnant model talks about the temporary body she wears, where she gained weight and the purpose of those changes for the baby.

For students, seeing a body like their own or talking with a trans person or someone with a disability who have fully fallen in love with themselves can be a very powerful experience. Student interests are diverse - from the hard sciences, computers, history, or fine arts - but every high school senior participates in the figure drawing class and is given the opportunity to appreciate the beauty in the diversity of human bodies and interact with the amazing people who inhabit them. Elizaveta knew this new approach would be a unique experience, and the greater impact it would have on our students social-emotional skills and opportunities for growth beyond artistic abilities.

For students, seeing a body like their own or talking with a trans person or someone with a disability who have fully fallen in love with themselves can be a very powerful experience.

Talking With our Littlest Students About Race

Adapted from Acorn Hill Waldorf Kindergarten

Children are constantly picking up on what is OK to talk about, what is off limits, and how adults react to the topic. Here's how to begin or continue a discussion about race with your child.

Like many other topics, race can be challenging for adults to discuss among themselves, let alone with their children. But while open dialogue about race is limited in our society, that doesn't mean you can't make decisions and set the tone for discussions about race in your home. Talking with young children about race is an opportunity - one you may or may not have experienced when you were growing up.

Some well-meaning parents feel if they do not address the topic of race, their children will be "color-blind." But the reality is that race does have meaning in our society. Your conversations with your child will depend on your own racial identity, the racial make-up of your family (immediate and extended), and your values regarding race—both those you express and those you imply.

Like other crucial conversations you might be beginning to have with your child right now, race discussions should start early and evolve as your child grows.

What They Understand

Kids under 24 months do not understand the adult meaning of race: the historical implications of it or how the history and current meaning of race affects our society, but babies and toddlers are beginning to notice differences in appearance. It might be that the child simply looks longer at or perhaps points to a person who looks different from the people she's most used to seeing in her everyday routines. During these moments, the child looks primarily to the adult to gauge their own interest and reaction—toddlers this young are still reliant on their parents' opinions and actions to shape their own. This goes without saying, but how you act around and discuss people from your own culture and other cultures is what your child will first consider appropriate. Toddlers internalize the beliefs of their family and immediate society, a process that will continue throughout their development.

Kids under 24 months do not understand the adult meaning of race: the historical implications of it or how the history and current meaning of race affects our society, but babies and toddlers are beginning to notice differences in appearance. It might be that the child simply looks longer at or perhaps points to a person who looks different from the people she's most used to seeing in her everyday routines. During these moments, the child looks primarily to the adult to gauge their own interest and reaction—toddlers this young are still reliant on their parents' opinions and actions to shape their own. This goes without saying, but how you act around and discuss people from your own culture and other cultures is what your child will first consider appropriate. Toddlers internalize the beliefs of their family and immediate society, a process that will continue throughout their development.

As the children grow, so does their awareness and their misconceptions about race. Studies have shown that by three years old, children are choosing playmates by race and by ages 4-6 their racial prejudices peak. By ages 5 and 6, children are already holding many of the viewpoints that the adults around them have on race. Not speaking to them about the topic means that they are making their own assumptions, and forming their own biases

What to Say

Say something! Your child's understanding of race begins both with what you will talk about and what you do not discuss. Children learn that when they ask a question about someone's race and they are shushed, it's not something they can discuss and is therefore taboo. Talking about race normalizes the topic and makes it less scary for kids.

As any parent who's caught their toddler staring at someone in the checkout aisle or pointing to a passerby in the mall will tell you, racial observations may be embarrassing. It really is important, though, for you to address your child's observations and take that moment to acknowledge the differences they are taking note of.

When your child points out (or later asks questions about) people with different skin color than his, address it. For example, if your child is white and asks why an African-American child's skin is brown, explain, "Grownups and kids have all different skin colors. Some have tan and some have brown." When possible, use accurate ethnicity language with your child: "She is white (or Caucasian)/African American (or black)/Latinx (or Hispanic)/Asian-American," etc.

When your child points out (or later asks questions about) people with different skin color than his, address it. For example, if your child is white and asks why an African-American child's skin is brown, explain, "Grownups and kids have all different skin colors. Some have tan and some have brown." When possible, use accurate ethnicity language with your child: "She is white (or Caucasian)/African American (or black)/Latinx (or Hispanic)/Asian-American," etc.

Though toddlers likely won't ask questions about race, children in preschool or grade school will have the vocabulary to articulate observations. Your child might ask why a person has skin a different color or hair a different texture than his. When he does make an observation or inquire about a race, answer the question and give correct information, which may mean doing some homework yourself. Think about and take responsibility for the stereotypes and assumptions we all have about race.

These are some basic ways you can prepare for a lifetime of conversations with your child about ethnicity and diversity

Self-reflect. Take some time and think about your own racial identity, the assumptions you hold, and what lessons you would like to teach your children about race. Talking with friends, family, and other parents can be really helpful. Look for other parents who are interested in open dialogue about race in their families. Talking with other adults will also give you clarity and increase your comfort level when answering questions if this is a challenge for you. Remember, this is often a scary process for adults. Understanding and challenging that fear will be helpful in conversations in your family.

Don't avoid the topic. Particularly in white families, some parents decide to not discuss racial differences. This reinforces that it is a taboo subject for your children. When you have had early conversations about appearances, for example, as your child gets older, you can also begin discussions about racism.

Don't avoid the topic. Particularly in white families, some parents decide to not discuss racial differences. This reinforces that it is a taboo subject for your children. When you have had early conversations about appearances, for example, as your child gets older, you can also begin discussions about racism.

Work on Empathy. Developing empathy comes from knowing your own feelings and beginning to understand feelings in others. How you interact with other people and respond to situations works on shaping that within your child. It may seem small and simple, but it is laying the foundation for how they treat, advocate for and think of others. Here are some Teaching Empathy Tips.

Look at your environment. Self-reflecting also means taking inventory of the images, stories and people that your child sees on a daily basis. Looking at your child’s toys, books, media influences, family, friends and neighborhood/community allows you to see areas for growth or conversation.

Read Books. Books are wonderful because they serve as windows into another’s world, reflections into your own, and give children the ability to connect with others. They also serve as good talking points for bringing up discussions about differences, injustice, and provide ways to celebrate and normalize diversity. Our Early Childhood Library offers a great selection of titles.

Monthly Observances Help Us Appreciate Our Diversity

Honoring and celebrating are wonderful ways to teach children about the diversity that makes our world such an amazing place. Part of our school's commitment to diversity, equity, inclusion and justice is to ensure that our curriculum, classroom activities and celebrations include a wide range of diverse and inclusive topics, and one way we do this is by connecting to monthly observances that are held in the wider culture of the United States. Diversity, equity, inclusion and justice work is brought to the students in the everyday classroom, but in addition, the monthly observances give teachers - from Early Childhood through High School - a touch point to making sure specific topics are being offered to our students. Here are just a few examples of monthly observances we share:

Honoring and celebrating are wonderful ways to teach children about the diversity that makes our world such an amazing place. Part of our school's commitment to diversity, equity, inclusion and justice is to ensure that our curriculum, classroom activities and celebrations include a wide range of diverse and inclusive topics, and one way we do this is by connecting to monthly observances that are held in the wider culture of the United States. Diversity, equity, inclusion and justice work is brought to the students in the everyday classroom, but in addition, the monthly observances give teachers - from Early Childhood through High School - a touch point to making sure specific topics are being offered to our students. Here are just a few examples of monthly observances we share:

Hispanic (or Lantinx) Heritage Month – September 15-October 15

Hispanic (or Lantinx) Heritage Month – September 15-October 15

Our high school students studied and presented on artist Frida Kahlo. Our Early Childhood Lending Library increased their stock of books about Latinx/Hispanic heritage and culture. Teachers read these books in class with the children and the children can take them home to read. It is important for children to have books in which they can see a reflection of themselves as well as a window into the world of another. Check out our Early Childhood Lending Library Catalog. Many of these books are in our Lending Library and almost all of them can be found in the public library.

Disability Awareness Month – October

So much of what Early Childhood aged children learn is from their environment and through play. We expanded our toy collection in honor of Disability Awareness Month to include inclusive and diverse dolls. Children can now play and care for dolls of all skin tones who have glasses, Down syndrome, a port-a-cath and asthma among others.

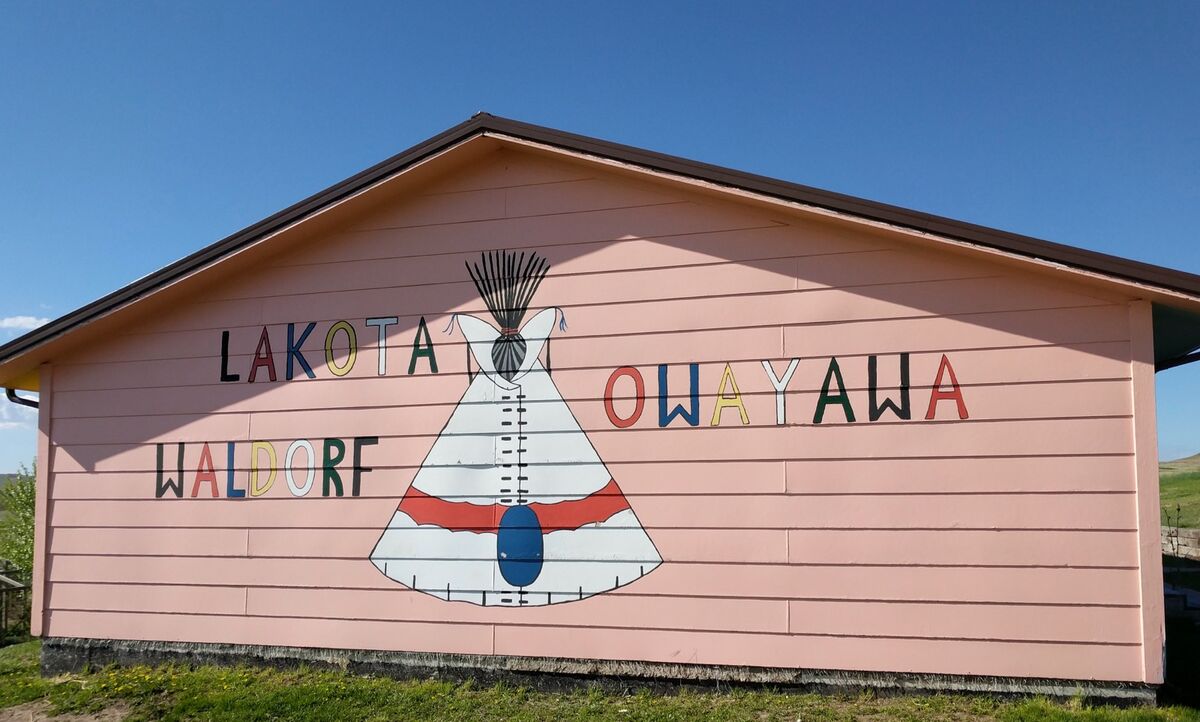

Native American/Indigenous Peoples Heritage Month – November

Native American/Indigenous Peoples Heritage Month – November

Our Grade Five class honored indigenous peoples as part of their daily blessing. Grade Three raised over $6,000 in a fundraiser for Lakota Waldorf School, our sister school on the Oglala Sioux reservation in South Dakota. And, our Early Childhood explored stories of local peoples and planned a visit by indigenous storyteller, Genot Picor, for an active presentation of story and movement about the peoples of the Great Lakes region.

Black History Month – February

Black History Month – February

Professor Peter Boykin presented at the High School about his family history which included the dismissal of his African American great-great-grandfather from West Point Military Academy after being wrongfully accused of staging his own assault. A book on the subject, Assault at West Point, was later made into a movie and a special ceremony at the White House with former-President Clinton, honoring Johnson Chestnut Whittaker and returning his bible, where he had kept his journal and which had been held by the government as evidence. The students were very engaged during his presentation and were eager to talk about what they could do personally to continue to strive for equality. We will be inviting Mr. Boykin to return to speak more about his family history and the future strive for equality during Black History Month.

We're proud of the long-standing efforts of our school community to recognize and honor all people. We look forward to honoring these months as well as others throughout this year and in future years, and we invite you to participate and share your thoughts, suggestions and celebrations with us!

· March - Women's History Month

· April – Earth and Ecology Month

· May - Asian Pacific Heritage Month

· June - Pride Month